Co-Authored by Kevin Hernandez

Anyone familiar with Disney films will know the song “Under the Sea” from their adaptation of The Little Mermaid by Denmark’s Hans Christian Andersen. How appropriate then that part of Denmark’s clean energy focus is under the sea with carbon capture and sequestration (CCS). Denmark also anticipates converting energy from the air with offshore turbines and moving green hydrogen through the region by ship and via onshore pipelines.

In June of 2023, ScottMadden leaders sponsored the Smart Electric Power Alliance’s fact-finding mission to Denmark to better understand that country’s energy transition and its push to be a regional leader in clean energy.

Many of those efforts center on the seas that surround Denmark. Led by Danish companies like Vestas, the country has been a pioneer in offshore wind power. And now, Denmark is pushing innovations such as green hydrogen production and CCS to address climate change.

As U.S. energy stakeholders review the economics of offshore wind, evaluate hydrogen’s potential, and explore CCS, their Danish counterparts may offer a glimpse of the future.

Water, Water (and Wind) Everywhere

Denmark’s unique geography—surrounded by the windy North and Baltic Seas—and robust experience with both offshore wind and oil development uniquely positions it to pioneer the seas’ potential to help the country achieve its ambitious climate goals.

Equally important is Denmark’s unanimity on support for climate action. Danes are investing heavily in companies and technologies to achieve a nationally mandated 70% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (from 1990 levels) by 2030 and CO2 neutrality by 2045.

To advance this, the Danish Parliament set a 2030 goal to increase solar and wind capacity by 250% and to lower thermal power capacity by 40%. This would result in 97% of the country’s electricity consumption coming from renewables by 2030, even as it is rapidly electrifying. Danish electric consumption is projected to grow 57% from 2019 to 2030.

As it pursues these internal goals, Denmark is also seeking to develop and export renewable energy to its North Sea neighbors and sell its climate technologies abroad in a bid to grow its economy. One such initiative is facing headwinds as cost remains a key consideration.

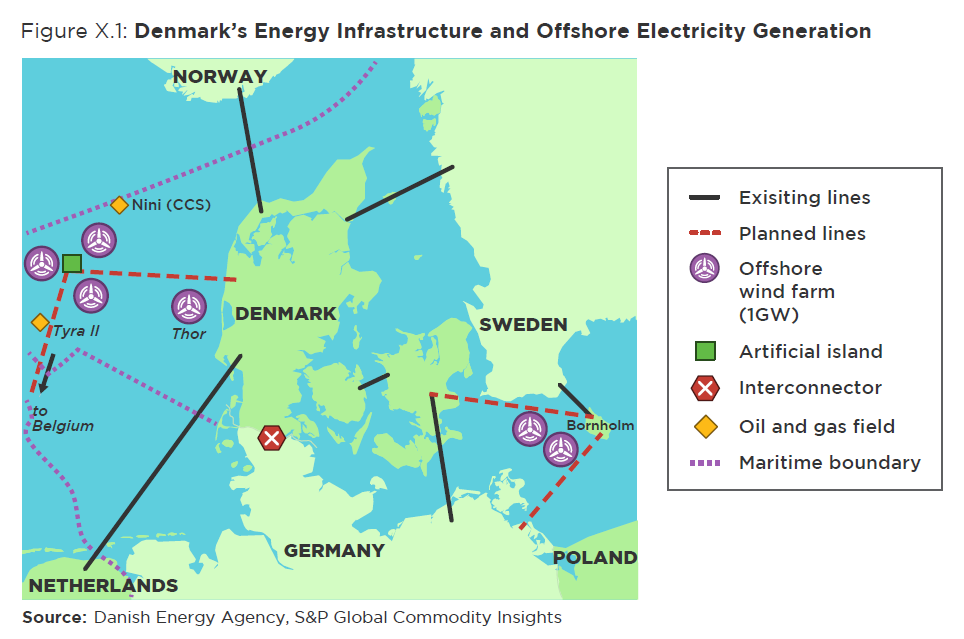

In 2020, Denmark launched a plan to develop artificial islands to serve as hubs to collect electricity from offshore wind farms and then push the electricity back home and to neighboring countries (see Figure 1).

While the island concept would enable developing wind further offshore and would be cheaper than developing transmission lines for each wind farm back to shore, its 50 billion DKK (approximately $7 billion USD) price has generated sticker shock and requires further analysis from the Danish government.

Figure 1. Denmark’s Energy Infrastructure and Offshore Electricity Generation

PtX and Green Hydrogen

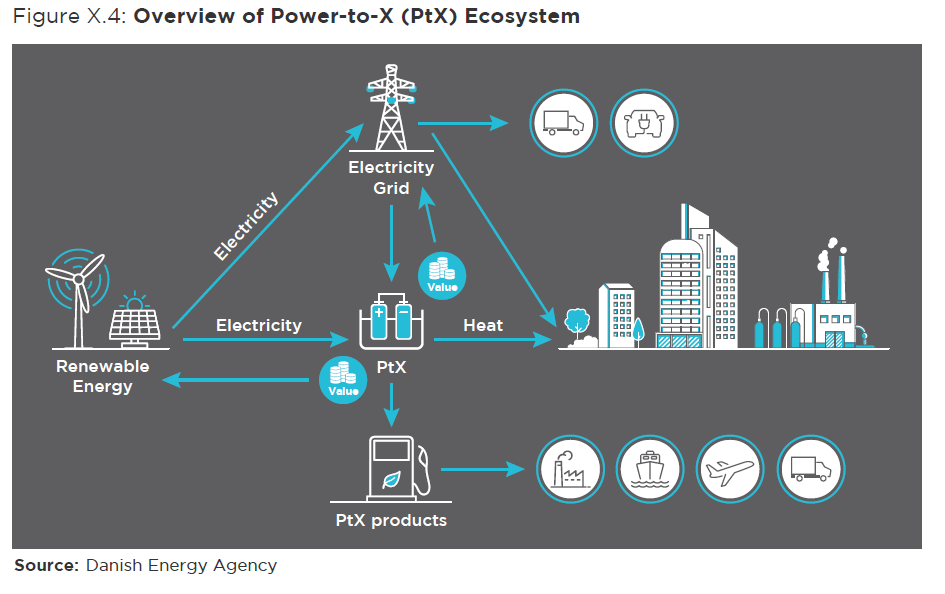

As global attention has turned toward addressing hard-to-abate emission sources such as aviation and shipping, which rely on liquid fuels, investment, and policy incentives have turned to potential solutions such as green hydrogen—hydrogen generated via electrolysis powered by clean energy sources.

In Denmark, technologies that produce fuels, chemicals, and materials based on green hydrogen are referred to as Power-to-X or PtX.

For areas of the Danish economy where electrification may be too expensive or difficult, the country has developed a strategy to use PtX to help decarbonize their energy needs and is investing in it.

The government plans to put 125 billion DKK (approximately $18 billion USD) toward supporting the development of PtX, supported by tariffs, an infrastructure for hydrogen buildout in Denmark, and a trading market for green hydrogen.

The PtX ecosystem envisioned by Denmark relies on abundant renewable energy to create hydrogen and other fuels that could be used in heating, transportation, or manufacturing applications (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overview of the Power-to-X (PtX) Ecosystem

Storing CO2: Underground and Under the Sea

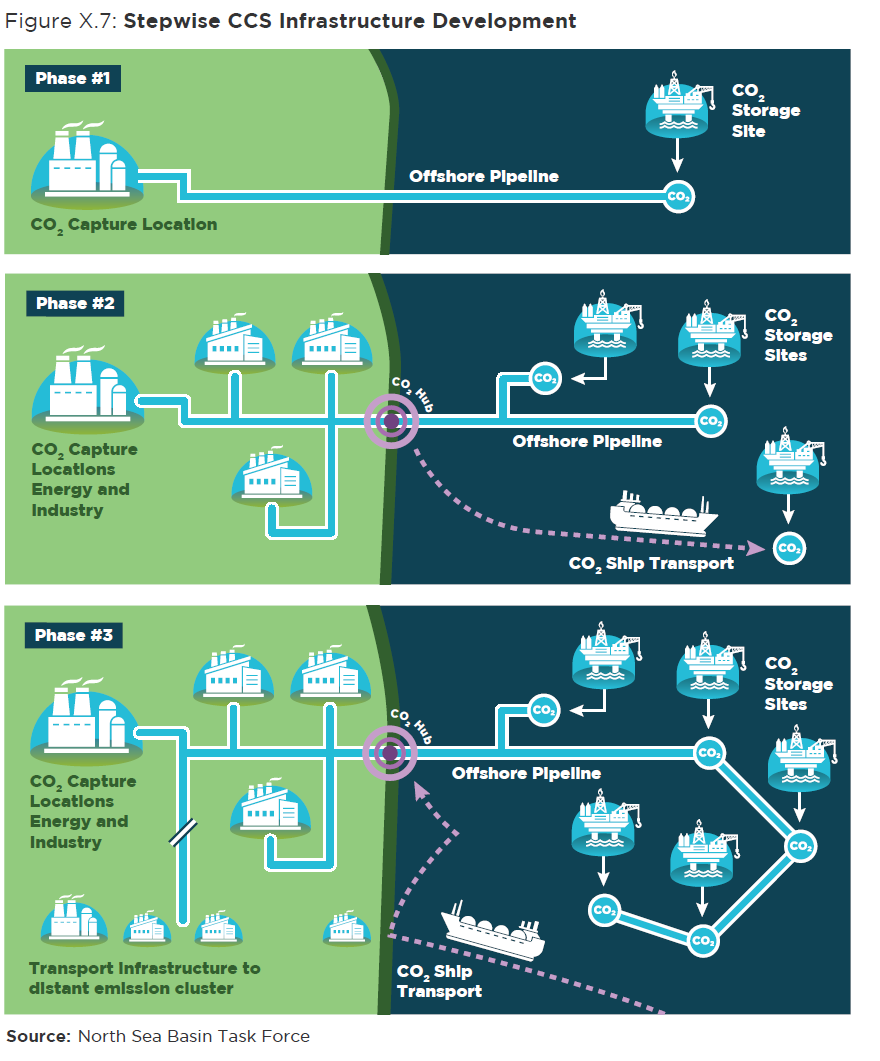

Denmark also seeks to become a regional CO2 storage leader, building an infrastructure for cross-border CO2 transport and storage.

The country has such ample storage capacity potential for CO2, both on land and offshore in depleted undersea oil and gas fields, that the country is actively exploring the potential to not only sequester and store its CO2 but to be a sink for neighboring countries’ CO2.

The North Sea Basin Task Force released a plan for an incremental buildout of such infrastructure—onshore, nearshore, and offshore. The initial activity would connect promising source clusters and storage sites. Future development would connect additional sources and sinks, upgrade pipelines and cluster hubs, and add ship loading and unloading (see Figure 3).

To kickstart CCS development, Denmark established two funds. One is a market-based, technology-neutral fund to support CO2 capture, utilization, and storage. The second fund supports the capture of biogenic CO2, with a goal of achieving negative reductions.

Figure 3: Stepwise CCS Infrastructure Development

Could It Happen Here?

If successful, Denmark will support the regional energy transition by offering neighboring countries relatively cheap, clean fuels and CO2 storage. They will also be well-positioned to support the global energy transition by exporting specialized technologies and services.

While U.S. policy support through the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law includes incentives for developing CCS and green hydrogen, the development of these nascent technologies in America faces a hurdle not seen in Denmark—the lack of broad and long-lasting support across stakeholders.

The fact-finding mission found a high level of unanimity in support of clean energy policies in Denmark. Voters, politicians, business leaders, and the government are aligned in their support for and investment in clean energy initiatives. Such support provides a stable environment for investment and business planning.

While CCS and hydrogen may develop in the United States without that support, these technologies and the businesses around them would likely face market challenges similar to those experienced by other clean energy technologies (e.g., solar and wind) over the previous decade.

As global market demand grows for clean energy technologies, U.S. stakeholders may begin to slowly build a consensus behind homegrown cleantech development for use at home and for profitable export.

In the meantime, we can continue to watch Denmark to see if they can bring these technologies to market in a manner that is cost-effective over the long term.