Inflation has hit the entire energy sector, and renewable energy is no exception. For decades developers fought to become competitive—then dominant––as the source of new power sector generation, and it’s worked for the most part.

While renewable energy costs fell fast over the past decade, those declines recently leveled off, and in some cases, reversed. But this temporary development doesn’t mean we should abandon clean energy or fossil fuel plant retirements.

To understand what’s driving renewable energy price changes, my colleagues and I interviewed energy market experts and reviewed publicly available cost data.

Our research shows the main factors driving renewable energy cost increases tend to be temporary, and costs are still competitive with fossil fuels, which suffered volatile price swings and drastic cost increases in 2022. While some localized projects have experienced high cost increases, the data shows average impacts have been modest.

Even with modest increases, wind, solar, and battery storage projects still provide ample market value. And the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) tax incentives will underpin long-term deployment and cost declines of these technologies that are core to cutting climate pollution.

Still, these cost increases expose flaws in how we plan the grid and regulate utilities. By taking a proactive approach to cost drivers like grid connection, labor force, and domestic supply chains, energy regulators and state energy officials can reduce developer risk and keep cutting costs as the market rebounds from inflation.

The state of renewable energy costs

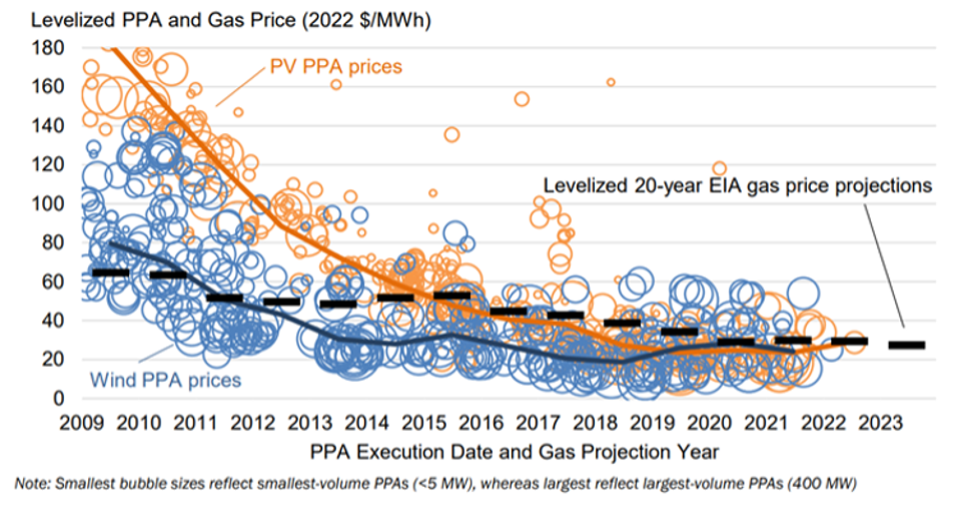

Lawrence Berkeley National Lab’s (LBNL) 2023 Utility Scale Solar and Wind Market reports show flattening and mildly rising clean energy costs are consistent across multiple datasets. LBNL analyzed utility-scale wind and solar contract prices, finding that from 2020-2022 they remained stable and competitive with gas.

Other data from Level Ten, which measures corporate renewable energy purchases, found similar trends with data up to 2023. Price increases have been higher in the corporate power purchase agreements than in the utility procurements collected by LBNL, reflecting economies of scale and greater offtake certainty associated with utility buyers. Even with these price increases, LBNL found most regions are profitable markets for new wind and solar projects.

LBNL also found coupling battery storage with solar projects only added modest additional costs – about 30-50% depending on project size. Batteries add reliability value while keeping projects competitive with other reliability resources like gas plants, and they can function on their own as power plants and grid infrastructure.

In late 2022, Bloomberg New Energy Finance observed battery pack prices slightly increased from $141 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) to $151/kWh, the first year-over-year price increase since Bloomberg began reporting data. However, lithium and other raw material prices fell precipitously in 2023, and the IRA has kick-started $70 billion worth of investments in a burgeoning competitive domestic battery manufacturing industry.

What’s driving cost increases, and where they are headed

Price increases come from a range of factors including trade policies, volatile commodities, supply chain snags, high interest rates, rising labor costs, and an inadequate grid.

The Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties (AD/CVD) and Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), including the uncertain guidance surrounding these policies, have created supply shortages for solar and battery components as foreign manufacturers struggle to get their products into the U.S. Meanwhile, critical components for clean energy like semiconductors, steel, and copper have seen significant supply crunch and price increases over the past year. IRA policies will expand the nation’s domestic manufacturing industry, but it will take a few more years before a robust onshore supply chain materializes.

Like the rest of the economy, clean energy industries are also contending with rising labor costs. Prevailing wage requirements are a condition to receive full IRA tax incentives, but labor-related costs and challenges have less to do with paying prevailing wages, and more to do with compliance documentation and bottlenecks for hiring qualified workers. Developing qualified labor is one area where federal and state policymakers can help alleviate near-term cost increases.

High interest rates are another key cost driver. While rates are high today and disproportionately increase the cost of capital-intensive renewables projects relative to fuel-based resources like natural gas generators, interest rates are inherently volatile and unpredictable. Morningstar predicts interest rates will fall from an average of 5% (real) in 2023 to 2% in 2026 – this would cut the cost of a typical utility-scale solar project 20%.

Renewable energy project developers now face considerably more risk due to rising interconnection costs and timelines. It now takes four to five years on average to move through the interconnection study process to completion – a doubling over the last decade. When average interconnection times increase, developers face increased cost of capital and overall risk to projects. Recent FERC action and grid operator attention to this issue has renewed interest on fixing outdated rules, but incumbent power in these markets and technical complexity make it difficult to change quickly.

What’s the future of renewable energy costs?

Recent cost increases make it more important than ever that policymakers keep supporting renewable energy and mitigating the barriers driving these increases. Slowing down on renewable energy could squander public health gains, reliability, consumer savings, and job creation. As uneconomic coal plants retire, adding wind, solar, and storage can avoid future capacity shortfalls.

While the market rights itself and cost pressures ease, several policy improvements can ensure we secure these benefits and insulate renewable deployment from future volatility.

First, utility regulators must enhance real-time feedback between market conditions and utility power plant contracts. Utilities seeking to protect their investments in existing fossil fuels may not regularly test the assumption these plants remain economic, risking an overcorrection of outdated estimates lasting several years. Regulators must ensure utility cost estimates track coming cost declines accurately to protecting consumers and overcome bias towards preserving the status quo.

Next, utilities and regional transmission operators must update interconnection and transmission planning rules to reduce grid connection risks and costs for clean energy projects. Grid regions like PJM and ISO-New England struggling with planning the grid for rapid interconnection can learn from Texas. While PJM delayed review of new interconnection applications until 2026, Texas has added solar and wind faster than any region, and times from interconnection application to agreement range from one to two years.

Building more lines is not the only way to increase transmission capacity – grid enhancing technologies (GETs) and advanced conductors are also cheaper and faster ways to upgrade the grid using existing lines. For instance, GETs can potentially enable renewable energy capacity to double, and advanced conductors could double the capacity of existing lines without needing major new permits. However, utility incentives can be misaligned with their consideration and use. To capitalize on existing rights of way, regulators should require utilities and transmission service providers consider GETs and advanced conductors in their planning processes.

Finally, states should focus their attention on attracting investment in domestic clean energy supply chains. The IRA incentivizes onshoring clean energy manufacturing, which should increase component supplies, reduce the impact of tariffs and create jobs across the country. Governors and state economic development offices have particular power to attract manufacturing to their state and should take this opportunity to identify what industries might be a best fit. In Georgia, for example, Governor Kemp committed to making the state a leader in electric mobility manufacturing – and $15 billion in new investment has followed since IRA passage.

Long-term, economies of scale should continue to reduce average wind, solar, and battery costs and sustained IRA support will create opportunities throughout the country to save consumers money. Policymakers concerned about cost increases should use all tools in their toolbox to integrate the changing dynamics of clean energy into decision-making while reducing the cost and risks for clean energy projects.