JHVEPhoto

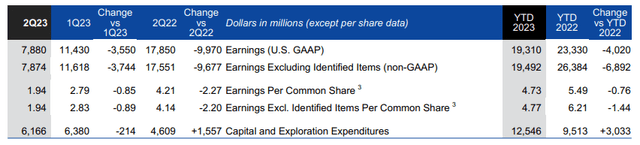

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM) posted Q2 earnings that are down sequentially and year-on-year:

Exxon Mobil Press Release

The bearish thesis is that the 2022 results were an anomaly sparked off by the geopolitical worries. As oil prices have receded from the triple digits, Exxon, and other energy producers would default to the lackluster returns of the prior years.

These arguments miss the point. Exxon doesn’t control the oil price and earnings will always vary with the commodity. Rather, Exxon’s job is to allocate capital among competing assets and maximize its capital returns for any given commodity price realization.

When adjusted for the oil price, Exxon’s return on capital employed (or ROCE) for 2022-2023 is superior to more than a decade of prior returns. XOM’s ROCE to oil price relationship is now more consistent with the late 1990s/early 2000s which was a better period for value creation in the industry.

For this reason, the past several quarters shouldn’t be dismissed as a fluke. I believe we are seeing a transformational change that will result in structurally higher capital returns for Exxon over the coming years. From this perspective, stock price comparisons to the 2010s should consider the vastly improved ROCE too.

Three ‘waves’ of ROCE in three decades

ROCE is a standard way to measure value creation in the energy industry:

Wall Street Prep

The numerator is net operating profit after taxes, i.e., excluding interest to account for different capital structures. The denominator reflects the total assets of the business, net of current liabilities which can be seen as a non-interest bearing source of financing.

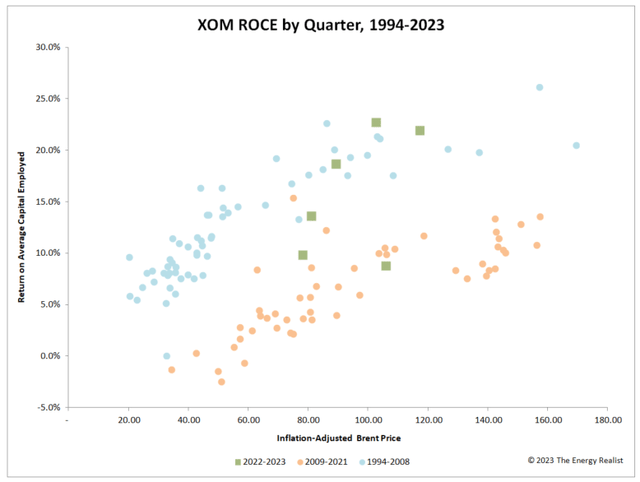

Going back to Exxon, I summarize below 30 years of annualized quarterly ROCE data, from 1994 to 2023, plotted against the inflation-adjusted Brent price (CO1:COM) for the respective quarters:

Author

I have highlighted two time periods that stand out as distinct ‘clusters’, 1994-2008 (‘pre-GFC’) and 2009-2021 (‘post-GFC’). Within both periods, there is a linear relationship between ROCE and the oil price. However, for the post-GFC period, ROCE is about 10% lower for the same oil price level.

Energy expert Arjun Murti has talked about a ‘high’ ROCE period from 1991 to 2006, followed by a ‘low’ ROCE period between 2006-2020. Paradoxically, as Murti notes, most of the low-ROCE period had higher oil prices, at least until 2014, but the returns on capital were nonetheless still poor.

One explanation, favored by Murti, is that ROCE is inversely related to investment and the low-ROCE period was characterized by chronic over-investment. However, I think there is more nuance to the story.

People forget this, but a few decades ago, Exxon and Chevron (CVX), along with the other majors, were valued not just for their oil reserves but also for their know-how. Back then oil-rich foreign countries were perhaps not as technologically sophisticated, so working with the majors offered the best way to unlock the value of their reserves.

However, sometime in the 2000s, national oil companies (or NOCs) started displacing the majors as highlighted by this Bain & Co article from 2012:

The rise to prominence of national oil companies has shifted the balance of control over most of the world’s oil and gas reserves. In the 1970s, the NOCs controlled less than 10% of the world’s oil and gas reserves; today, they control more than 90%. This dramatic reversal has increased the ability of NOCs to source financial, human and technical resources directly-once the exclusive domain of the large integrated oil companies (IOCs) and independents-and to build internal capabilities. Consequently, IOCs and independents face new challenges to remain relevant to the NOCs, as well as the government resource holders they represent, in all but the most difficult projects.

Further, Bain noted at the time that NOCs were “becoming increasingly comfortable and adept at procuring human and technical resources from oilfield services companies, which have grown dramatically in size and capability.” In other words, if you are an NOC, why not cut out the middleman and work directly with a Schlumberger (SLB) or a Halliburton (HAL)?

This dynamic is part of the reason why I am structurally more bullish on the oilfield services component of the energy sector, but with regard to Exxon or Chevron one could also see the post-GFC overinvestment as driven by necessity as much as by greed. If NOCs chose to develop the highest ROI assets by themselves, that logically leaves the lower return prospects for the majors.

‘Back to the future’

The good news, going back to the ROCE scatterplot, is that the oil price-adjusted 2022-2023 numbers are moving back to the 1994-2008 ‘high ROCE’ trendline. For five of the past six quarters, ROCE has been much higher than in the 2009-2021 period, when the inflation-adjusted Brent price was similar.

This says to me that we are seeing a structural change, which I would attribute to the cost-cutting and optimization efforts that were spurred by the 2020 low-point. Investment has also been lower and perhaps better placed strategically. This bodes well for the future because if the 2020s ROCE exceeds the returns from the 2010s, Exxon’s stock price should also be positioned for higher highs than in the prior decade.

Exxon has higher ROCE than the other majors

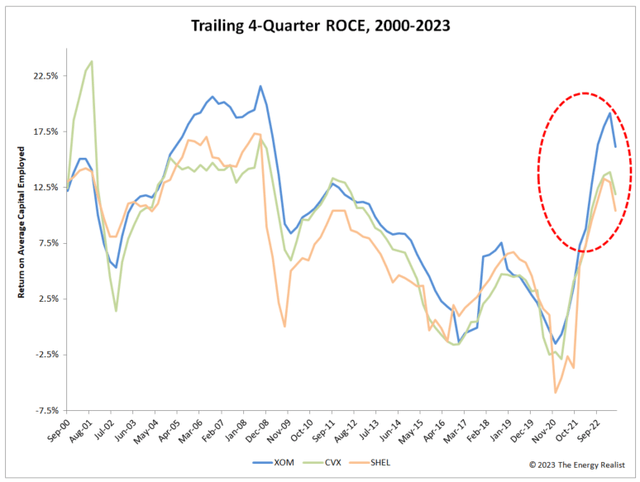

The ROCE trend I describe mostly applies to the other majors too, but I would note that Exxon has opened a bit of a gap over Chevron and Shell (SHEL):

Author

For most of the last two decades, the majors generated consistent ROCE, but Exxon has led Chevron and Shell by about 5% over the latest quarters. Interestingly, Exxon also had an advantage during 2006-2008.

Bottom line

An investment in Exxon shouldn’t be treated as an outright bet on oil prices. Exxon’s function is to maximize the return it generates on its capital for any pricing environment. When adjusting for the oil price, there is evidence that, after a decade of generally mediocre ROCE, Exxon is now generating higher returns consistent with the 1990s/2000s period. If the ROCE trend continues, I would expect Exxon’s stock price to reach new all-time highs too.

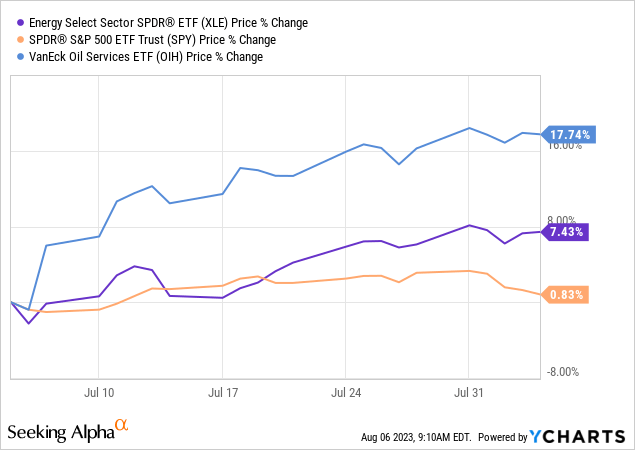

Over the last month we have also seen some signs that energy is turning again from a market laggard into a leader:

However, it is noteworthy that oilfield services (OIH) are outperforming the broader energy sector. I am very bullish on Exxon, but I am even more bullish on the services sector, given that much of the current capex expansion is being fueled by NOCs.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.