Environmental and community advocates in Massachusetts argue that making too much room for biofuels in a pending state plan to decarbonize heating systems would slow the transition from fossil fuels and cause more pollution than a plan that prioritizes electric heat pumps.

As the state works on the creation of a Clean Heat Standard, a report released last month by Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility raises questions about the effects using biodiesel in fuel-oil heating systems could have on air quality and public health, saying there is not enough information available about the pollutants released in the process.

Advocates say there is no such uncertainty about electric heat pumps, which create no direct emissions and should therefore be heavily favored in the new state policy.

“We absolutely think the thumb should be on the scale of electrification,” said Larry Chretien, executive director of the Green Energy Consumers Alliance. “If they give credit to biofuels, it ought to be conditional.”

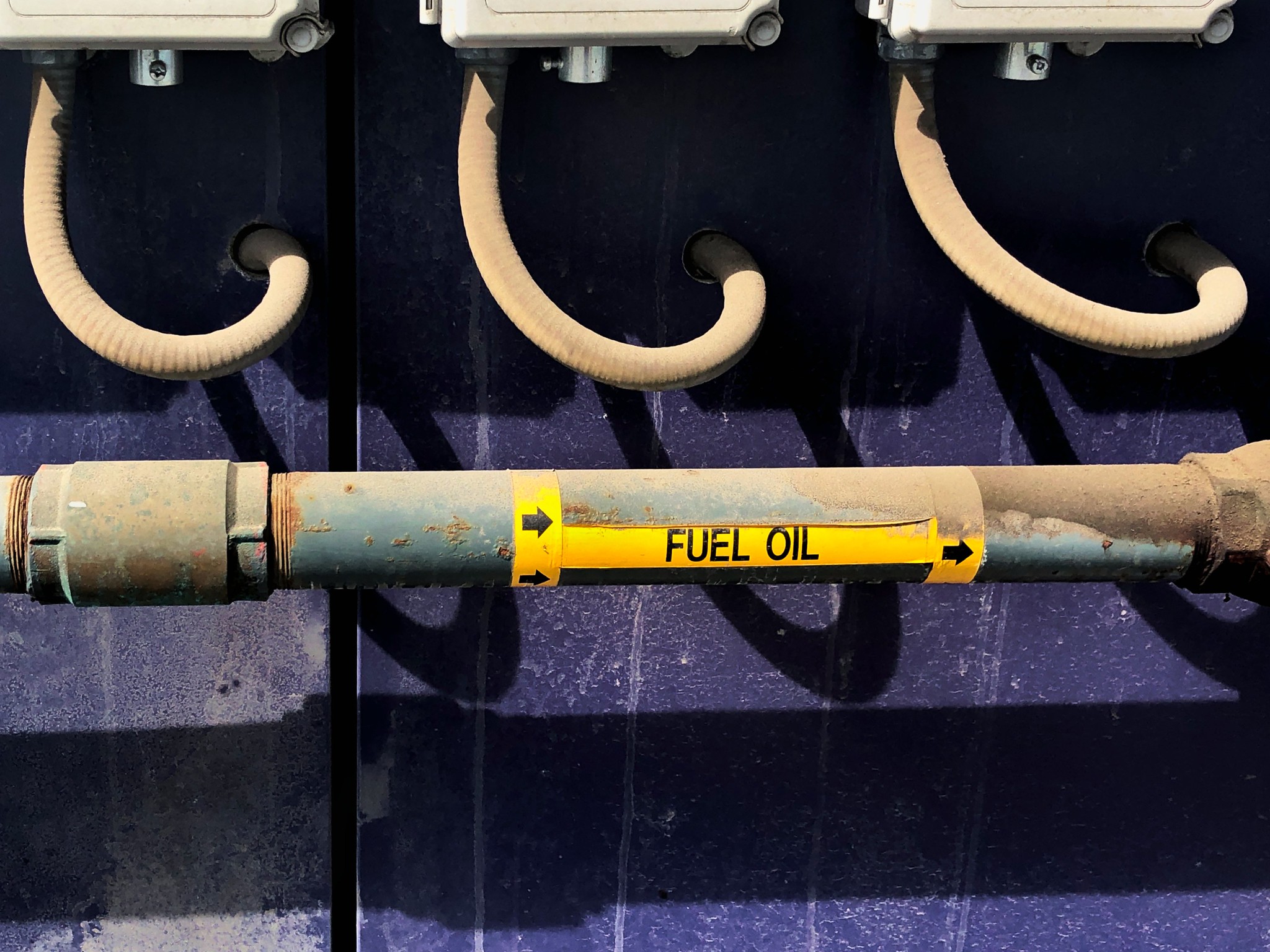

Oil heating is much more prevalent in the Northeast than in the rest of the country. In Massachusetts, 22% of households are heated with oil, as compared to less than 5% nationwide. Moving homes and businesses off oil heat, therefore, is an important element of the state’s plan to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, which sets a target of reducing emissions from heating by 93% from 1990 levels in that timeframe.

The process of developing a Clean Heat Standard began when then-Gov. Charlie Baker convened the Commission on Clean Heat in 2021. In 2022, the board recommended the creation of the standard, which was also included in the state’s Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2050, released later that year. A stakeholder process began in 2023, and in the fall of that year the state released a draft framework for the standard that included the expectation of issuing credits for some biofuel use.

Open questions about public health

The program is expected to require gas utilities and importers of heating oil and propane to provide an increasing proportion of clean heating services like home heat pumps, networked geothermal, and other options, or buy credits from other parties that have implemented these solutions.

Whether the other options that qualify as clean heat will include biofuels — fuels derived from renewable, organic sources — has been a matter of contention since the idea for the system was first raised.

Climate advocates have tended to oppose the inclusion of much, if any, biofuel in the standard. Though biodiesel creates lower lifetime greenhouse gas emissions than its conventional counterpart, the recent Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility report contends that there are many unanswered questions about how burning biodiesel impacts public health.

“Given the sheer amount of doubt, there’s more research that should clearly be done before these fuels are subsidized by the state government,” said report author Carrie Katan, who also works as a Massachusetts policy advocate for the Green Energy Consumers Alliance, but compiled the report as an independent contractor for the physicians group.

The physicians’ report notes a study by Trinity Consulting Group that found significant health benefits to switching from fossil diesel to biodiesel for building heating. The physicians’ report, however, questions the methodology used in that study, claiming it cherrypicks data and fails to cite sources.

Katan’s report also notes that the health impacts of biofuels can vary widely depending on the organic matter used to create them, and points out that most of the research on burning biofuels is focused on the transportation sector.

Climate advocates also argue that embracing biofuels in a Clean Heat Standard would unnecessarily prolong the transition to electric heat pumps while encouraging the continued burning of fossil heating oil. Typically, a heating oil customer using biodiesel receives a blend that is no more than 20% biofuel. Providing credit for that fraction of biofuel would therefore improve the economics of the entire heating oil system, contrary to the overall emissions reduction goals of the policy, Chretien said.

“We’re trying to create a system that is rewarding steps towards greenhouse gas reduction,” he said.

Making the case for biofuel

Advocates of biofuels, however, say they are confident that existing science makes a solid case for the health and environmental benefits of biodiesel.

“There’s a decades-long body of work showing the overall benefits to public health of biofuels, specifically biodiesel,” said Floyd Vergara, a consultant for Clean Fuels Alliance America, a national trade association representing the biodiesel, renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel industries.

Vergara, who was involved in the Trinity Consulting study, called out in the physicians’ report, also defended the methodologies and sourcing of that paper.

Further, he said, though biodiesel is typically limited to 20% in current blends, it is quite possible to run a heating system entirely on biofuel, with just a few tweaks to the equipment. These conversions could yield immediate reductions in emissions, he said, rather than waiting for the slower process of replacing thousands of heating oil systems with electric heat pumps.

The difference could be particularly acute in low-income or other traditionally disadvantaged neighborhoods, where many residents can not afford to make the switch to heat pumps, he said.

“You’re getting those benefits immediately, and you’re getting them while the states are pursuing zero-emissions technologies,” he said.

State environmental regulators expect to release a full draft of the clean heat standard for public comment some time this winter.