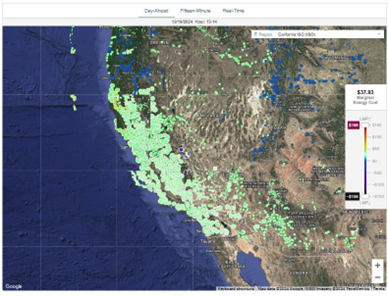

Ever since your editor can remember, variable electricity pricing has been a sought-after dream that always seemed to be just around the corner. As everyone knows, wholesale electricity prices vary with time of day, day of week and seasonally. To be more precise, they also vary by location as noted on the map for California. But there is no consensus on what is the best way to calculate and convey these variations as retail prices to consumers. Are wholesale prices on competitive markets the correct ones to pass on to customers? And if so, how frequently and with what level of granularity? Should price signals also reflect locational variations? Should we distinguish between customers based on their quantity and/or pattern of consumption – for example, by what devices they own (e.g. tariffs for EV owners) or by charging different prices to different devices at the customer site? Countless books, papers and articles have debated the pros and cons of these issues over many decades.

Delivering price to devices at last

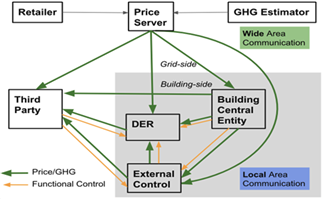

Below is the CalFlexHub system architecture. It clarifies what entities exist, and the types of communication between them

To reach electricity pricing Nirvana, three major issues have to be addressed:

First, what are the best electricity prices to offer;

- Second, how best to communicate the prices to customers; and

- Third, what are the best options to get electricity using devices to respond to prices – since empirical evidence suggests that consumers respond only in limited ways, such as start charging their EVs at midnight.

With the widespread proliferation of digital communication, sending signals to customers’ smart meters and beyond – to individual communicating devices – appears feasible, once standards and protocols are in place.

Communicating with customers’ electricity using, producing or storing assets is not at hand yet but as this article explains progress is being made. The major obstacles are retailers currently not offering sufficiently dynamic prices, and lack of consensus on uniform standards and protocols. These would allow the price signals to reach all sorts of devices, enabling them to respond automatically using pre-set commands or assisted by third parties as shown schematically on the accompanying figure.

Wholesale prices vary by time and location in California

Many academics, researchers and innovators have been working in all these areas and a consensus is emerging that we may finally be close to achieve what has always been a distant and insurmountable dream. Your editor reached out to Bruce Nordman, a researcher at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), to find out the latest in all three areas. LBNL is conducting the CalFlexHub research project for the California Energy Commission (CEC) to examine and demonstrate the needed communication and flexible load technologies.

On pricing, Nordman refers to CalFUSE, a scheme proposed by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) as a possible starting point for setting prices. He said,

“While it includes the wholesale generation cost as a component, it also includes components for transmission and distribution system costs that vary each hour with the relative loading on these with a quadratic function. This provides much more dynamic range than the wholesale price alone and can provide enough for a compelling value proposition to the customer to shift loads.”

Once a pricing scheme is agreed and accepted,

“In the long run, retailers should set prices that result in the best overall outcome for the grid which will often not be a direct calculation from the wholesale energy price. Making this change won’t affect the downstream technology for communication or price usage. We may want to move to shorter time intervals, e.g. half-hour or 15-minute. While 5-minute is of course possible, with a lot of storage on the grid it may not be worth it.”

Regarding what is the best way to deliver the prices to consumers and their devices, Nordman believes that the standard open protocol OpenADR 3.0 should be the answer.

“OpenADR 3.0 was introduced in the fall of 2023 and is simple and modern (and so easy to implement) but still can support a wide variety of demand flexibility coordination. OpenADR 3.0 is particularly suited to sending such prices, both from the grid to a central customer device to receive them, as well as within the customer site. While sending prices directly to individual devices will also be utilized, there are many advantages to indirect communication through a customer gateway device.”

The third hurdle requires the cooperation of manufacturer of devices and appliances to implement price response capabilities.

“Manufacturers will wait to support native price response until such prices are both available and communicated in a standard way. With the communication now clear, we need enough retailers to offer such prices and consumers to take them up for the market opportunity to become clear. Initial support will be with cloud-based optimization as that is easier for manufacturers to deploy, but there are many advantages to doing the optimization on-site and we will see a migration to that over time.

Clearly the key is to deliver meaningful price signals to customers and their devices. Nordman said progress is being made in this area when,

“Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) began offering such prices (hourly; different every day) in December 2024, and Southern California Edison (SCE) is to follow a few months later. Prices are day-ahead, with a forecast for the following six days. Prices vary by location, with the area covered having about 400,000 people on average.”

These developments suggest that, at least in California,

“Pricing is ready for rapid and wide scale-up, and will have many benefits. However the introduction of large amounts of PV export and EV charging creates issues for distribution systems, and while pricing reduces these, it will not eliminate the problem. We need a parallel solution for capacity on feeders where this is an issue. Australia does this today for PV export (using IEEE 2030.5). OpenADR 3.0 also supports the PV export mechanism, as well as a second one designed around the EV import case.”

Nordman’s answer to the first hurdle, how to calculate and convey useful prices to consumers, is Highly Dynamic Pricing or HDP, which he defines as prices that are “at least hourly” and “different every day” based on the supply and demand conditions on the grid.

Nordman posted his vision of how HDP can be applied on 5 Dec 2024 on the Electricity Brain Trust (EBT), a professional social network, starting with what is broadly accepted by nearly everyone who knows anything about the subject, i.e., customers should not be in the communication path (paraphrased),

” … manual use of prices is completely unrealistic – it has to be automated.”

The good news is that “We have the technology available today – we just need to deploy it.” Nordman, for example, explains that his own “… heat pump controller – a commercial product that provides space heat and hot water – is optimizing to hourly prices right now.”

While not everyone is as savvy about such things as he is, Nordman points out that

“Millions of people – mostly in Scandinavia – pay such retail prices today. They are ahead in deploying prices, but we are ahead in thinking about automation. The automation starts with a ‘price server’ that is like a web server but instead of distributing web pages to people, it distributes prices to machines or devices.”

And as already noted, starting in Dec 2024 Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) began offering an hourly retail price that is different for every hour of each day – consistent with the definition of Highly Dynamic Price or HDP. Moreover, using OpenADR 3.0 PG&E’s price server sends out tomorrow’s guaranteed prices each day plus six additional days of forecast prices. This allows Nordman’s heat pump controller, which also uses OpenADR 3.0 (though it isn’t yet linked to the PG&E price server) to receive and react to the price signals. He says,

“This is the future. No intermediaries are needed to take money out of the system. With HDP customers get 100% of the value of their demand flexibility.”

There may be room for aggregators to capture any residual demand flexibility or controllable loads that customers cannot capture on their own, particularly on the extreme weather days.

“Many customers will want to pay a third party a small amount for optimization services for devices that can’t natively be price responsive. Such third parties can compete for this so that customers can pay low prices. On-bill payment of this should be instituted. Aggregators on the other hand – working on a completely different business model – take most of the money.”

Heat pump controller can respond to variable prices

Nordman is not keen on the demand flexibility aggregator model in which the aggregator skims off most of the value from customers’ inherent demand flexibility. They offer a useful service but capture most of the commercial value of the aggregated demand flexibility in the process. They are, at best, a second-best option when customers cannot monetize on their own. Aggregators understandably emerged when HDP and the necessary automation were not available.

For all the obvious reasons Nordman is convinced that it is prime time for introducing HDP.

“Pricing is the future. It is higher performing and lower cost than other approaches. It is peculiar that just charging a good price for a product is controversial, but that is how strange the electricity business is. Pricing is the only mechanism that can work in any country, any building type, in any context including off-grid and/or disconnected from the Internet.”

His original post on the Electricity Brain Trust (EBT) received a number of responses, which he subsequently summarized and paraphrased on a follow-up post on 13 Dec 2024. Below are a few comments he received and his responses:

- Most people don’t want to track electricity prices

Of course, that is the whole point of HDP – with automation, you don’t have to. My heat pump controller already optimizes to HDP and I pay no attention to it.

- Pricing is super complicated

True but in practice using prices is much simpler in many ways than the alternatives. It is also higher performing, e.g., doing things that cloud-based approaches are unable to do.

- HDP is risky

With the PG&E hourly tariff now available, the bill is calculated at the HDP tariff and the Otherwise Applicable Tariff (OAT; likely always the time-of-use or TOU) and the customer pays the lower of the two amounts. This is a sound approach and should be emulated. Fixed or less-dynamic prices – which are currently the norm – offer a form of insurance and we know that insurance comes with a premium – so we should expect average bills under an HDP tariff to be lower than with TOU.

- HDP won’t solve the problem

Of course not. But we can fill in with aggregators around the edges, particularly for extreme weather or high/low demand periods. Perhaps the aggregators can do 10% of the work while pricing does the remaining 90%. We also need to manage distribution system capacity in coordination with customers.

- HDP is bad for equity

Sample of PG&E hourly prices offered starting Dec 2024

Nordman says he is as concerned about equity as anyone else but notes that HDP is the lowest cost flexibility mechanism available, hence the best way to achieve the lowest bills. The TOU-based ceiling on the bills, as noted above, ensures that customers can’t be worse off. The faster we get price response into the market, the sooner it will become a default feature.

He remembers when adding Ethernet or Wi-Fi to a PC meant adding a new board of hardware into a slot inside. But over time, it became a default feature. We, of course, need to do as much as possible to facilitate access to modern price-responsive devices and external controls for legacy products.

Referring to what happened during an extreme winter storm in 2021 in the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) where Griddy Energy sent sky-high electricity bills to customers and was forced to file for bankruptcy protection, Nordman says the debacle was an informative example of how dynamic prices can backfire.

It is easy to design and build an airplane that cannot fly. That says nothing about whether airplanes can fly. Millions of people pay HDP today and save money by doing so. We know that airplanes can fly and, similarly, HDP prices can be at the center of flexibility.

- HDP is about utilities controlling my stuff

On the contrary, the aggregator business models have someone else control your stuff for their benefit and the utility’s. With HDP, you have complete autonomy and privacy. There is no need for the utility to be involved.

- HDP is real-time prices

No. Many people assume that prices that vary for every hour of every day must be calculated directly from wholesale energy prices. This is nonsense. While doing so would be much better than what we do today, it is not the right answer. That said, the communication and automation are disjoint from how the prices are calculated so we have plenty of time to figure this out.

Other commentary that Nordman received included observations such as:

- Customers hate complexity

So do I. That is why I want simple automated price response.

- Low-income customers already pay too much for electricity and progress on cost-effective price response by some customers will reduce bills for all

Agreed. A study by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) showed this exact point.

- Everyone needs a trusted agent

HDP type pricing gives the customer complete flexibility as to who optimizes their loads. I expect that some non-profit organizations will provide price optimization to low-income or maybe all customers for free. On the Internet we see a profusion of free software and services, from web browsers to email and more. Price response is no different. Once it is commonplace, services will emerge.

- Community Choice/Power/Energy Aggregators can play an important role

Agreed. In Europe and Australia retailers commonly provide optimization services. In places where Community Choice Aggregators (CCAs) are established such as in California, they also have the incentives to provide such services.

Nordman adds that he has recently purchased his first EV and is “… searching for a charger company that can integrate with hourly prices – and have my eye on a future day when I no longer have symmetric import/export prices so that my excess solar will be worth much less. This is where a ‘local price’ is essential to correctly optimize for customer benefit.”

Pointing to a screenshot from PG&E website which shows real hourly prices for the day (visual), Nordman notes that, “This is not the complete retail price – I don’t know yet how much gets added underneath. But the dynamic range is impressive – over $0.90/kWh difference between the highest and lowest price. Other days have much less dynamic range, but grid conditions are different every day” – which is what needs to be conveyed to consumers and their programmable devices.

Nordman believes that “HDP is one critical key to a better electric future. The sooner we move in that direction the more money we will save and the more greenhouse gases we will cut. We need to start from the future state that we want to achieve then work backwards to the present. Our present path of making small incremental changes without a long-term vision cannot deliver.”

https://docs.google.com/document/d/192M44SJHxvcKhcQYiMzoiO_-RsSROTAnNd6GcS5Bopc/