A year ago, the U.S. announced ambitious plans to build large-scale clean hydrogen hubs. Now, 12 months later, those plans have advanced little and are still shrouded in uncertainty.

Last October, the U.S. Department of Energy picked seven consortiums across the country to receive up to $7 billion in federal grants. The goal of this startup money? To help the hubs attract tens of billions more in private-sector investment to pay for construction costs. These projects, located around the country, aim to bring together a wide array of organizations to scale up the production, storage, and transport of low- and zero-carbon hydrogen, which some experts view as a way to replace fossil fuels in industries such as steelmaking and aviation.

There’s still little publicly available information to indicate whether these “clean hydrogen hubs” are likely to attract the needed private sector investment, however. Just as opaque are their potential community and climate impacts.

Environmental groups, community advocates, and energy experts have grown concerned that the projects are off track — and increasingly dismayed that the DOE and the hub projects are not giving them the transparency needed to confirm or deny these worries.

This puts the DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, the agency responsible for the H2Hubs program, in a tricky position.

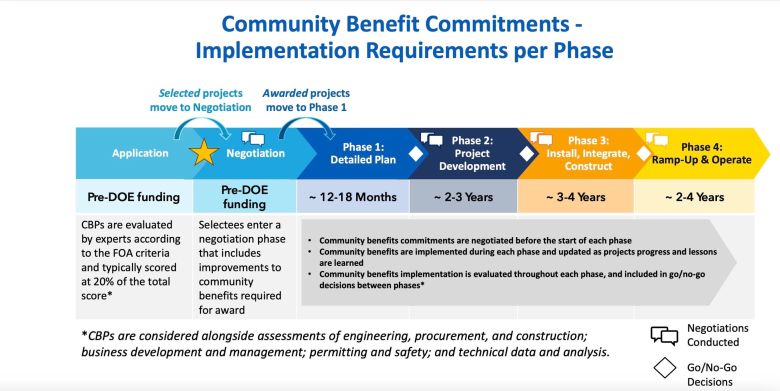

The $7 billion in H2Hub awards is being doled out in phases, over the course of many years. It’s OCED’s job to make sure the hubs are hitting the technical, financial, and community-benefit milestones needed to earn these disbursements.

The hydrogen hubs are a cornerstone of not only the Biden administration’s clean hydrogen strategy, but its overall approach to clean energy. Without the hubs, the U.S. may not be able to supply the tens of millions of tons per year of clean hydrogen needed to decarbonize key industries in the decades to come.

“We know that jump-starting a new clean energy economy in the U.S. is going to take time and public and private sector investment,” Kelly Cummins, OCED’s acting director, told Canary Media in an October interview. “To do that right and make sure it’s sustainable, we need to engage communities in a new way.”

However, community and environmental groups hounding the hydrogen hubs and DOE for information over the past year say that engagement isn’t happening. The Natural Resources Defense Council reported in May that “environmental justice advocates and frontline communities have largely been kept in the dark on key details and basic information about many of these projects.”

Since then, relatively little additional information has emerged. “We’re still struggling at this point to understand what’s really going on with the hubs,” said Morgan Rote, director of U.S. climate at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), another nonprofit group that’s been tracking the disconnect between hydrogen hubs and communities.

“I don’t think DOE is sitting on a whole wealth of information they’re not sharing,” Rote said. “But that makes it even more challenging — and it’s no wonder communities feel like they don’t have information, if the DOE doesn’t have information.”

Cummins acknowledged these frustrations.“The tension here is that we’re still in early days,” she said. “We’ve been working to engage communities and special interest groups. But we’re just at the start of this learning process.”

The initial planning grants are just the first step in what OCED expects to be an eight- to 12-year pathway to full-scale ramp-up and operations. Each stage will involve its own series of “go/no-go” decisions, with a “long list of deliverables and criteria,” Cummins said.

To date, only three hubs have been awarded first-phase planning grants of about $30 million each: the ARCHES hub in California; the Pacific Northwest Hydrogen Association(PNWH2), which includes Oregon, Washington, and Montana; and the Appalachian Regional Clean Hydrogen Hub (ARCH2), which includes Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. The remainder are still in the process of negotiating final approval for their first-phase funding.

“We’ll go through a review of all that — the financing, the technology, the community benefits — and then make a decision if they’re ready to move from Phase One to Phase Two,” she said. “And there are some instances where we might decide they are not moving to Phase Two.”

Measuring progress on first-of-a-kind hydrogen hubs

Less than 1 percent of global hydrogen production today is low-carbon. Of the roughly 90 million tons per year produced globally and 10 million tons per year in the U.S., almost all is derived from fossil gas.

Right now, the two main methods for making low- or zero-carbon hydrogen are far more expensive than dirty hydrogen — and also untested at scale. Those include so-called “blue hydrogen,” which is made from fossil gas combined with carbon capture, and “green hydrogen,” which is made by splitting water in electrolyzers powered by zero-carbon electricity.

The hydrogen hubs need about $40 billion in private-sector investment to match DOE’s $7 billion. That’s a tough sell for investors, given the uncertain economics involved both for would-be clean hydrogen producers and for the industries that must invest in retrofitting facilities, building new infrastructure, and reconfiguring how they do business in order to use it.

What’s more, the rules for a subsidy that could make clean hydrogen cost-competitive with dirty hydrogen — the 45V production tax credits created by the Inflation Reduction Act — have yet to be finalized.

Last December, the U.S. Treasury Department proposed rules that would require green-hydrogen producers to source newly built and consistently deliverable clean electricity — restrictions that energy analysts say are vital to ensure hydrogen production doesn’t end up increasing carbon emissions.

But those proposed rules are being challenged by a number of industry groups and politicians who say they’ll stifle the nascent industry — including the seven hydrogen hubs themselves. The Treasury Department aims to finalize the rules by January.

The regulations for blue hydrogen remain another point of contention. Only the California and Pacific Northwest hubs have pledged to not make hydrogen from fossil gas. Some hubs, such as the Appalachian hub, have made blue hydrogen a focus. But blue hydrogen has yet to be proven to be cost-effective at scale, and in some cases could lead to more carbon emissions than simply using fossil gas.

The unresolved nature of these regulations — and the projects themselves — makes it impossible to tell at this point whether the hubs will actually help fight climate change.

In a May letter to DOE, U.S. Representatives Jamie Raskin (D-Maryland) and Donald S. Beyer Jr. (D-Virginia) complained that the agency has touted the potential for hydrogen made by the hubs to reduce carbon emissions by 25 million metric tons per year, but has “yet to publish the projected lifecycle emissions linked to the production of hydrogen.”

That information is “overdue and critical for us to fully understand the precise climate and public health impacts of the H2Hubs program,” the lawmakers wrote. “Scientists have warned that high levels of lifecycle emissions from hydrogen production could entirely cancel out any climate benefits from replacing fossil fuels with hydrogen.”

Cummins noted that DOE has responded to this request for information. “But the response was focused on the fact that we are evaluating every aspect of the production and use of hydrogen so that we can understand the impact on the environment,” she said — and much of that work remains to be done.

Are the hydrogen hubs living up to their community commitments?

Though it may be early days for the hubs, advocates say the projects could be operating in a much more transparent way.

OCED released summaries of each hub’s commitment to community benefits immediately after the hubs were selected last October. Since then, OCED has held more than 70 meetings with more than 900 individuals and groups participating, Cummins said. The office has also briefed about 4,000 individuals and groups, including community members, environmental justice organizations, labor and workforce organizations, first responders, local businesses, energy professionals, elected tribal leaders, and local, state, and federal government officials.

The feedback from those meetings has led OCED to add new requirements for the hubs. The projects now must create public data reporting portals to share information as it’s finalized. They must develop community advisory structures that allow groups to provide feedback on plans as they’re developed. And they must “jointly evaluate or pursue negotiated agreements” on labor, workforce, health and safety, and community benefits plans.

“We’re really focused on three-way communication” between OCED, hub participants, and affected communities and other groups “to make sure anything we’re hearing back from the community is adequately addressed,” Cummins said. “That will determine whether we move forward to the next phase of the process.”

Environmental and community groups worry these requirements may still not prevent hub participants from running roughshod over communities, however.

In particular, many fear that participants — including oil and gas giants such as bp America, Chevron, Enbridge, EQT, ExxonMobil, Sempra Energy, and TC Energy — will subject communities already burdened with fossil fuel pollution to further harms from hydrogen production.

Communities have “questions around the transparency for the selection and planning process, how to monitor and evaluate community benefits plans, and to ensure there are sustained community benefits after the duration of the grants,” said Cihang Yuan, a senior program officer at the environmental nonprofit World Wildlife Fund. Other concerns include “more local impacts, such as hydrogen leakage or chemical disasters,” she said. “It’s definitely important for these hubs to have a solid plan for safety of operations.”

The secretive approach that hubs have taken to sharing information with potentially affected communities has added to these concerns. In California, the ARCHES hub requires meeting participants to sign non-disclosure agreements barring them from sharing information about the hub’s activities under threat of legal penalties.

“That’s something we can’t do,” said Theo Caretto, associate attorney at California-based environmental justice group Communities for a Better Environment (CBE), since it would bar community groups from sharing information with their constituents.

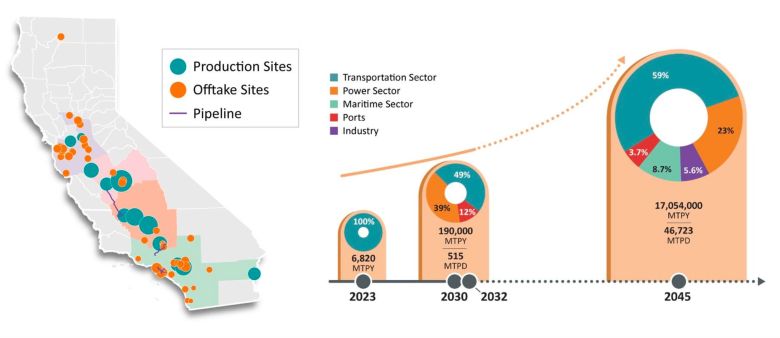

Those non-disclosure rules have remained in place at ARCHES and other hubs despite continual protests, forcing groups like CBE to wait for public information to dribble out. But one year in, “we’re having difficulty getting specifics on which projects are being funded,” Caretto said. “They’ve given out fact sheets and publications,” such as the map and chart below in a May report from ARCHES to DOE. “But those are still quite general and don’t give specifics about what each project is.”

The Ohio River Valley Institute has raised similar concerns about the ARCH2 project in Appalachia. In a May letter to DOE signed by 54 nonprofit and community groups, Tom Torres, the institute’s hydrogen campaign coordinator, said communities have had “no substantive opportunity to shape this proposal while negotiations continue behind closed doors.”

The saving grace, he wrote, is that “nothing so grievous has been done that cannot be undone. Money has yet to flow to these projects and ground has not been broken.”

Giving communities authority over how major energy infrastructure is planned and built would be a departure from how large industrial projects have historically been pursued.

“There is this dichotomy, this tension, between the project development deadlines and long-term robust engagement processes that will be needed to meet these community benefits plans obligations and gain community trust,” said Mona Dajani, global co-chair of energy, infrastructure and hydrogen at law firm Baker Botts and lead counsel for the HyVelocity hub in Texas.

DOE’s commitment to ensuring that hubs will meet the Biden administration’s Justice40 Initiative — its pledge to direct at least 40 percent of climate-related federal spending to communities “historically impacted by energy development and burdened with policies of exclusion and disinvestment,” as Dajani put it — heightens the importance of community involvement.

This will “add a lot of complexity to development processes. But they’re doing their best.

It’s definitely going to be challenging to be transparent when it’s not all finished,” Dajani said.

Will private-sector players commit to spending the money?

Amidst questions around community benefits and lifecycle carbon emissions, much of the hype that fueled oversized clean-hydrogen projections in the past few years has started to deflate. Major project announcements have been delayed or put in limbo, leading analysts to question whether ambitious government clean-hydrogen production targets can be reached in the coming decade.

This retrenchment is also a threat to U.S. hydrogen hubs, which must convince companies and their financial backers to commit to the tens of billions of dollars of investment needed to scale up clean hydrogen to compete against the fossil fuels it is meant to displace.

That challenge is already rearing its head at the Appalachian ARCH2 hub, a pet project of a lawmaker key to getting the hydrogen hub program passed as part of the 2022 Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill — retiring Democratic U.S. Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia.

Manchin praised the ARCH2 hub’s potential to revitalize the economy of his home state and the greater Appalachian region at an August event marking DOE’s approval of its first-phase grant. “I’m happy to know that I was able to play a part in this to be able to have a future for my children and grandchildren,” he said.

But, as is true for all of the hub projects at this point, it’s far from clear that ARCH2 will deliver on its promise of becoming a clean energy economic engine for the region.

In a report released this week, the Ohio River Valley Institute noted that several projects initially identified as part of the ARCH2 plan have since dropped out. Those include Canadian gas producer and pipeline owner TC Energy and industrial chemicals giant Chemours, which canceled plans to develop two green hydrogen production sites in West Virginia.

“The various hydrogen hubs and their individual projects are much more tenuous than many people imagine,” Sean O’Leary, senior researcher at the Ohio River Valley Institute and the author of the report, told Canary Media. “These projects are still heavily dependent on private markets to come up with the funds.”

In an attempt to fill the gap left by those departures, ARCH2 recently issued a call for companies to propose projects, which could receive up to $110 million if selected. “Originally you could argue that we had projects that were seeking federal funds,” O’Leary said. “Now, we have federal funds seeking projects.”

Cummins said that OCED has anticipated that hub participants may drop out or be added throughout the early stages. “That’s OK. We don’t want a company that for any reason doesn’t want to participate to be stuck in something they don’t see as economically viable.”

At the same time, OCED will vet new entrants on the same criteria applied to those that initially applied: “Are they technically feasible? Do we see a path to financial viability? What does their workforce plan look like? And finally, what do their community benefits look like?”

In an email to Canary Media, T.R. Massey, spokesperson for Battelle, the research organization managing the ARCH2 hub, echoed a key refrain about the projects: “The important context to remember is these new hydrogen hubs, including ARCH2, have just entered the first phase.”