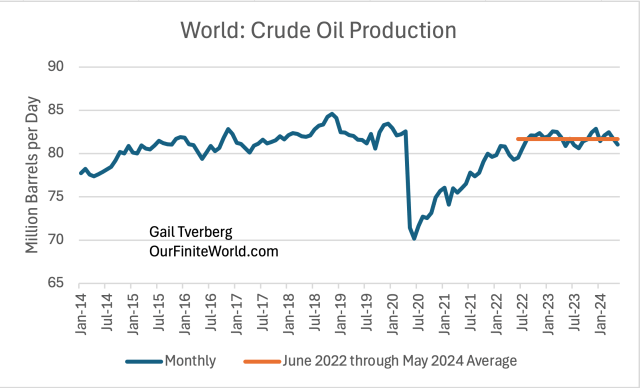

World crude oil extraction reached an all-time high of 84.6 million barrels per day in late 2018, and production hasn’t been able to regain that level since then.

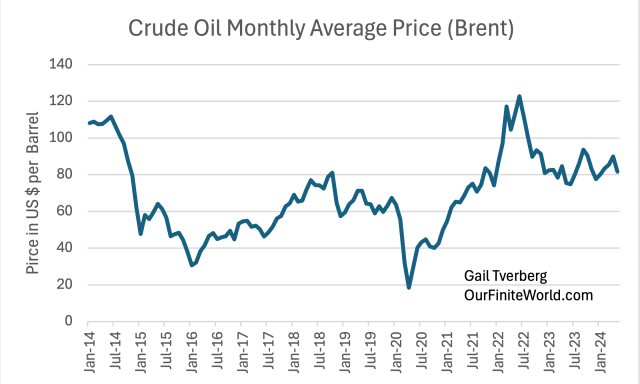

Oil prices have bounced up and down over the ten-year period 2014 to 2024 (Figure2).

In this post, I show that changing oil prices have had varying impacts on production. Recently, lower prices seem to be associated with lower production because extraction has become less profitable for producers. A temporary spike in oil prices does little to raise production. The view of economists that crude oil extraction can continue to rise indefinitely because lower production leads to higher prices, which in turn leads to greater production, is not true. (Economists also believe that substitutes can be helpful, but this is not a subject I will try to cover in this post.)

[1] World crude oil production has not regained its level prior to the Covid restrictions.

According to EIA data in Figure 1, the highest single month of crude oil production was November 2018, at 84.6 million barrels per day (mb/d). The highest single year of crude oil production was 2018, when world crude oil production averaged 82.9 mb/d. The last 24 months of oil production have averaged only 81.7 mb/d of production. Compared to the year with the highest average production, world oil production is down by 1.2 mb/d.

Furthermore, in Figure 1, there is nothing about the world production path in the last 24 months that gives the impression that oil production will be surging upward anytime soon. It merely increases and decreases slightly.

World population continues to grow. If economists are to be believed, oil prices should be shooting upward in response to rising demand. However, oil prices have not generally been increasing. In fact, as of this writing, the Brent crude oil price stands at $69, which is lower than the recent average monthly price shown in Figure 2. There is concern that the US economy is going into recession, and that this recession will cause oil prices to fall further.

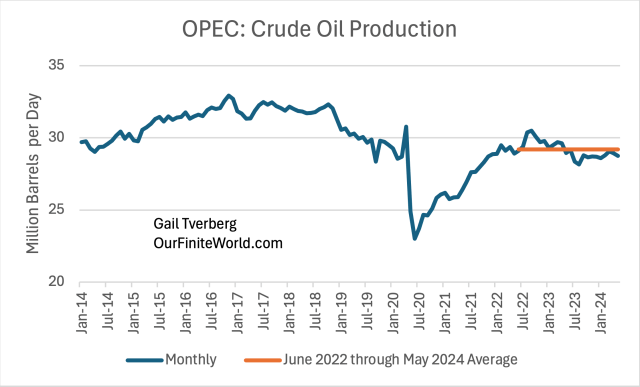

[2] OPEC oil production seems as likely as other source of production to be influenced by price, since OPEC sells oil for export and can theoretically cut back easily.

One thing that is somewhat confusing about OPEC’s oil production is the fact that the membership of OPEC keeps changing. The data the EIA displays is the historical production for the current list of OPEC members. If former members left OPEC because of declining production, this would be hidden from view.

Based on the EIA’s method of displaying historical OPEC oil production, the peak in OPEC production occurred in November 2016, at 32.9 mb/d. The highest year of oil production was 2016 at 32.0 mb/d, with 2017 and 2018 almost as high. Average production during the last 24 months has been 29.2 mb/d, or 2.8 mb/d lower than the 32.0 mb/d production in its highest year. Thus, recent OPEC production has fallen further than world production, relative to their respective highest years. (World production is down only 1.2 mb/d relative to its highest year.)

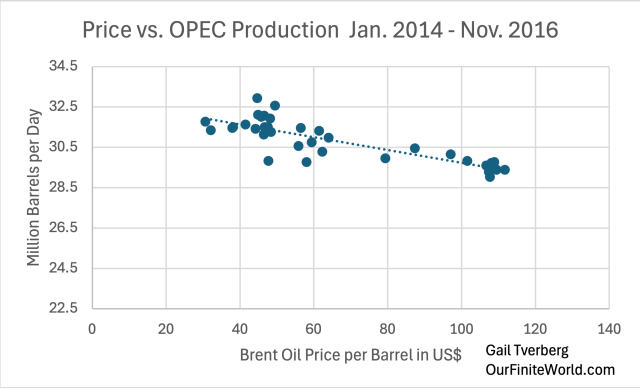

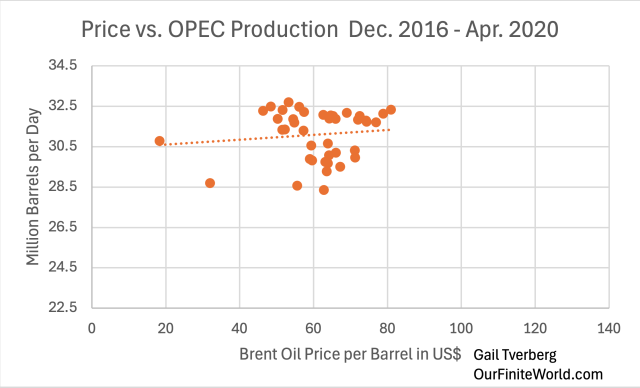

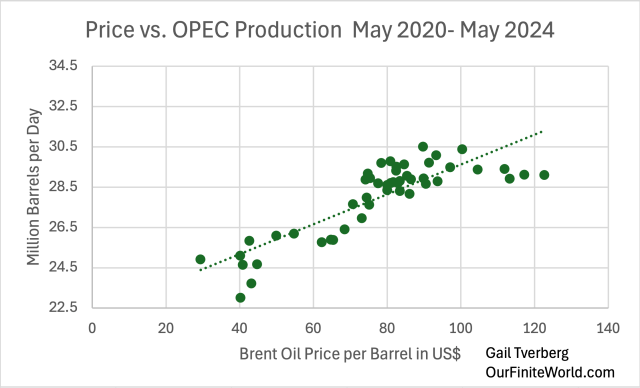

[3] An analysis of OPEC’s production relative to price indicates that patterns change over time.

Prices have changed dramatically between 2014 and 2024. I chose to look at prices versus production during three different time periods, since these periods seem to have very different production growth patterns:

- January 2016 to November 2016 (rising OPEC production)

- December 2016 to April 2020 (falling OPEC production)

- May 2020 to May 2024 (rising and then falling OPEC production)

These are the three charts I created:

During this initial period ending November 2016, the lower the price of oil, the more OPEC’s Oil production increased. This approach would make sense if OPEC was trying to keep its total revenue high enough to “keep the lights on.” If some other country (such as the United States in Figure 7) was flooding the world with oil, and through its oversupply depressing prices, OPEC didn’t choose to respond by cutting its own production. Instead, it seems to have pumped even more. In this way, OPEC could make certain that US producers weren’t really making money from their newly expanded supply of crude oil. Perhaps the US would quickly cut back–something it, in fact, did between April 2015 and Nov. 2016, shown in Figure 7 below.

During this second period ending April 2020, prices plunged to a very low level, but production didn’t change significantly. It is difficult to change production levels in response to a specific shock because the whole system has been set up to provide a certain level of oil extraction, and it takes time to make changes. Other than that, prices didn’t seem to have much of an impact on production.

In this third period ending May 2024, OPEC producers seem to have been saying, “If the price isn’t high enough, we will reduce production.” Figure 6 shows that with higher prices, the amount of oil extracted tends to rise, but only up to a limit. When prices temporarily hit high levels (in March to August of 2022–the dots over to the right in Figure 6), production couldn’t really rise. The necessary infrastructure wasn’t in place for a big ramp up in production.

Perhaps if prices had stayed very high, for very long, maybe production might have increased, but this is simply speculation. Oil companies won’t build a lot of extraction infrastructure that they don’t need, regardless of what they may announce publicly. I have been told by someone who worked for Saudi Aramco (in Saudi Arabia) that the company has (or at one time had) a lot of extra space for oil storage, so that the company could temporarily ramp up deliveries, as if they had extra productive capacity readily available, but that the company didn’t really have the significant excess capacity that it claimed.

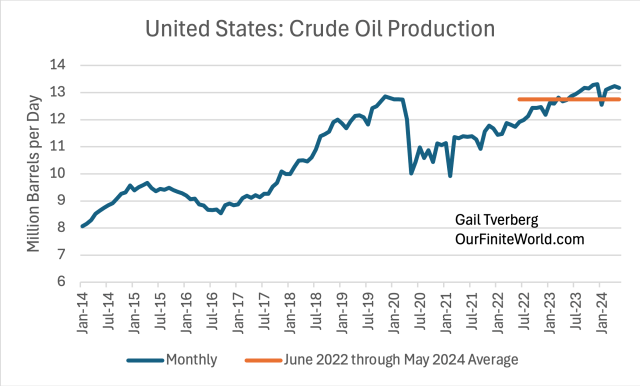

[4] US oil production since January 2014 has followed an up and down pattern, to a significant extent in response to price.

Figure 7 shows three distinct humps, with the first peak in April 2015, the second peak in November 2019, and the third peak in December 2023.

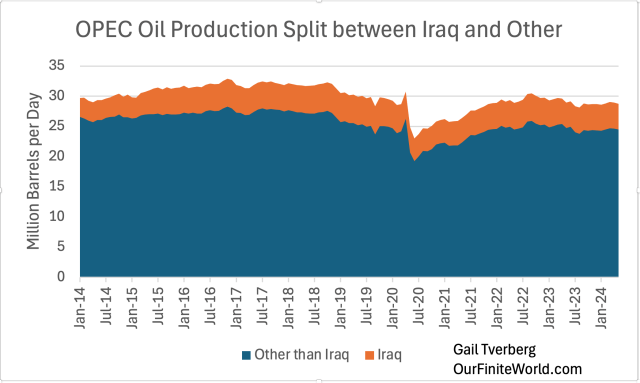

In the first “hump,” there was an oversupply of oil when the US was trying to ramp up its domestic oil supply of oil (through tight oil from shale) at the same time that OPEC also increasing production. The thing that strikes me is that it was OPEC’s oil supply in Iraq that was ramping up and increasing OPEC’s oil supply.

The rest of OPEC had no intention of cutting back if the US was arrogant enough to assume that it could raise production of both US shale and of Iraq with no adverse consequences.

Looking at the detail underlying the first US hump, oil production rose between January 2014 and April 2015 when production was “stopped” by low prices, averaging $54 per barrel in January through March 2015. The US reduced production, particularly of shale, since that was easy to cut back, hitting a low point in September 2016. The combination of growing oil supplies from both the US and OPEC led to average oil prices of only $46 per barrel during the three months preceding September 2016.

Eventually OPEC oil production peaked in November 2016 (Figure 3), leaving more “space” available for US oil production. Also, oil prices were able to rise, reaching a peak of $81 per barrel in October 2018. World crude oil production hit a peak in November 2018 (Figure 1). But even these higher prices were too low for OPEC producers. They announced they were cutting back production, effective January 2019, to try to further raise prices.

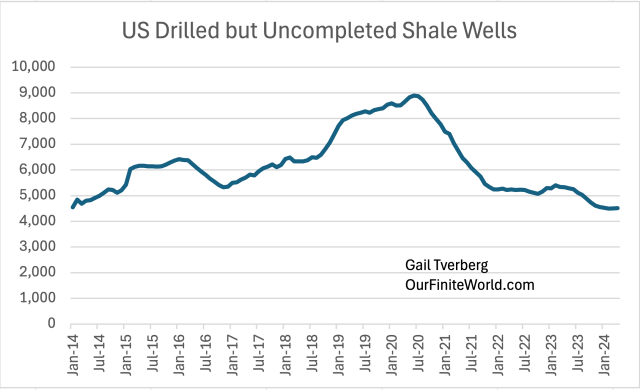

During the second hump, US oil production rose to 12.9 mb/d in November 2019. The oil price for the three months preceding November 2019 was only $61 per barrel. Evidently, this was not sufficient to maintain oil production at the same level. The number of “drilled but uncompleted wells” began to rise rapidly.

Drillers chose not to complete the wells because the initial indications were that the wells would not be sufficiently productive. They were set aside, presumably until prices rise to a high enough level to justify the investment.

Figure 7 shows that the US oil production had already started to fall before the Covid-related drop in oil production, which began around April and May of 2020.

[5] The rise in US oil production since May 2020 has been a bumpy one. The peak in US oil production in December 2023 may be its final peak.

The rise in oil production since May 2020 has included the completion of many previously drilled but uncompleted (DUC) wells. There has been a trend toward fewer wells, but “longer laterals,” so the earlier wells drilled were probably not of the type most desired more recently. But these previously drilled wells had some advantages. In particular, the cost of drilling them had already been “expensed,” so that, if this earlier cost were ignored, these wells would provide a better return to shareholders. If production was becoming more difficult, and shareholders wanted a better return on their (most recent) investment, perhaps using these earlier drilled wells would work.

There remain several issues, however. Currently, the number of DUCs is down to its 2014 level. The benefit of already expensed DUCs seems to have disappeared, since the number of DUSs is no longer falling. Also, even with the addition of oil from the DUCs, the annual rise in US oil production has been smaller in this current hump (0.8 mb/d) than in the previous hump (1.4 mb/d).

Furthermore, there are numerous articles claiming that the best shale areas are depleting, or are providing production profiles which focus more on natural gas and natural gas liquids. Such production profiles tend to be much less profitable for producers.

I think it is quite possible that US crude oil production will start a gradual downward decline in the coming year. It is even possible that the December 2023 monthly peak will never be surpassed.

[6] Oil prices are to a significant extent determined by debt levels and interest rates, rather than what we think of as simple “supply and demand.”

Debt bubbles seem to hold up commodity prices of all kinds, including oil. I have discussed this issue before.

Figure 1.

” data-image-description data-image-meta=”{“aperture”:”0″,”credit”:””,”camera”:””,”caption”:””,”created_timestamp”:”0″,”copyright”:””,”focal_length”:”0″,”iso”:”0″,”shutter_speed”:”0″,”title”:””,”orientation”:”0″}” data-image-title=”43. Interest rates and size of debt bubble determine how high oil prices rise” data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/ourfiniteworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/43.-Interest-rates-and-size-of-debt-bubble-determine-how-high-oil-prices-rise.png?fit=640%2C359&ssl=1″ data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/ourfiniteworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/43.-Interest-rates-and-size-of-debt-bubble-determine-how-high-oil-prices-rise.png?fit=300%2C168&ssl=1″ data-orig-file=”https://i0.wp.com/ourfiniteworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/43.-Interest-rates-and-size-of-debt-bubble-determine-how-high-oil-prices-rise.png?fit=995%2C558&ssl=1″ data-orig-size=”995,558″ data-permalink=”https://ourfiniteworld.com/2018/12/20/electricity-wont-save-us-from-our-oil-problems/43-interest-rates-and-size-of-debt-bubble-determine-how-high-oil-prices-rise/” data-recalc-dims=”1″ decoding=”async” height=”359″ loading=”lazy” role=”button” src=”https://energynews.today/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/43.-Interest-rates-and-size-of-debt-bubble-determine-how-high-oil-prices-rise.png” tabindex=”0″ width=”640″>

It seems to me that all the manipulations of debt levels and interest rates by central banks are ultimately aimed at maneuvering oil prices into a range that is acceptable to both producers of crude oil and purchasers of crude oil, including the various end products made possible through the use of crude oil.

Food production is a heavy user of crude oil. If the price of oil is too high, one possible outcome is that food prices rise. If this happens, consumers become unhappy because their budgets are squeezed. Alternatively, if food prices don’t rise sufficiently, farmers find their finances squeezed because they cannot get a high enough return on all of the required farming inputs.

[7] The current debt bubble is becoming overstretched.

Today’s debt bubble is driving up stock prices as well as commodity prices. We can see various pressures around the world associated with this debt bubble. For example, in China many homes have been built in recent years primarily for investment purposes, rather than residential use. This property investment bubble is now collapsing, bringing down property prices and causing banks to fail.

As another example, Japan is known for its “carry trade,” which is made possible by the combination of its low interest rates and higher rates in other countries. The Japanese government has a very high debt level; it cannot withstand more than a very low interest rate. There is significant concern that this carry trade will unwind, an issue that has already been worrying world markets.

A third example relates to the US, and its role of holder of the US dollar as reserve currency, which means that the US dollar is used heavily in international trade. Historically, the holder of the reserve currency has changed about every 100 years, in part because the high demand for the reserve currency allows the government holding the reserve currency to borrow at lower interest rates than other countries. With these lower interest rates, and the need to pull the world economy along, there is a tendency to “spur asset bubbles.” But an asset bubble is likely to have a debt bubble propping it up.

My previous post raised the issue of the economy today being exposed to a debt bubble. There has been excessive borrowing in many sectors of the economy that have been doing poorly. Commercial real estate is an example, as witnessed by many nearly empty office buildings and shopping malls. People with student loan debt often delay starting a family because they are struggling with repayment of those loans.

If any or all these bubbles should burst, there could be a swift downward fall in oil prices and commodity prices, in general. This could be a major problem because producers would tend to leave the market, and world GDP, which depends on energy supplies of the right kinds, would fall.

[8] Oil is an international commodity. Disruption of demand by any major user could pull prices down for everyone.

China is the single largest importer of oil in today’s world. Its economy seems to be struggling now. This, by itself, could pull world oil prices down.

[9] We don’t often think about the fact that oil prices need to be both high enough for producers and low enough for consumers.

Economists would like to think that oil prices can rise endlessly, allowing more oil to be extracted, but history shows that this is not what happens. If there are too many people for the available resources, wage and wealth disparity tends to increase, leading to many more very poor people. Lots of adverse things seem to happen: the holder of the reserve currency tends to change, wars tend to start, and governments tend to collapse or be overthrown.

[10] Simply because crude oil is in the ground and the technology seems to be available to extract the crude oil doesn’t mean that we can necessarily ramp up crude oil production.

One of the major issues is getting the price up high enough, and long enough, for producers to believe that there is a reasonable chance of making money through a major new investment. The only time that oil prices were above $100 for a sustained period was in the 2011 to 2013 period. On an inflation-adjusted basis, prices also exceeded $100 per barrel in the 1979 to 1982 period based on Energy Institute data. But we have never had a period in which oil prices exceeded $200 or $300 per barrel, even after accounting for inflation.

The experience of 2014 and 2015 shows that even if oil prices rise to high levels, they do not necessarily remain high for very long. If several parts of the world respond with higher oil production simultaneously, prices could crash, as they did in 2014.

There is also a need for the overall economic system to be available to support both the extraction of and the continuing demand for the oil. For example, much of the steel pipe used by the US for drilling oil comes from China. Computers used by engineers very often come from China. If China and the US are at odds, there is likely to be a problem with broken supply lines. And, as I said in Section 8, disruption of demand affecting even one major importer, such as China, could bring demand (and prices) down significantly.

[11] Conclusion.

The crude oil situation is far more complex than the models of economists make it seem. World crude oil supply seems to be past peak now; it may be headed down significantly in the next few years. Central banks have been working hard to keep oil prices within an acceptable range for both producers and consumers, but this is becoming increasingly impossible.

We live in interesting times!