By Michael Shank and US Congressman Lloyd Doggett

This year we’re headed for a very hot summer. The National Weather Service predicts hotter-than-normal conditions almost everywhere. And that’s saying something, given that last year was the hottest year on record. So, be sure to look for shade and water—lots of it.

With a drastic spike of heat-related deaths in the U.S. over the past few years, time is of the essence. We must take action at the local, state, and federal levels to reverse this deadly trend. Cities, in response, are getting creative about responding to heat. Local governments offer compelling and creative communication approaches to raise awareness—like the City of Austin implementing a Heat Resilience Playbook to identify citywide and neighborhood-based projects and programs to address extreme heat and Miami-Dade County hiring Chief Heat Officers to focus the public’s and policymakers’ attention on the urban heat island crisis. Other cities, like Phoenix, Arizona, are launching “Summer Heat Safety” campaigns with a Heat Relief Network to guide residents toward local cooling stations.

Increasingly, cities are declaring Heat Health Emergencies and coming up with creative “heat response” programming to educate the public on how to stay safe and stay cool when the temperatures are intolerable. They’re also building Resilience Hubs to serve as go-to community spaces during extreme weather. This is game-changing and life-saving work in response to rising heat in cities.

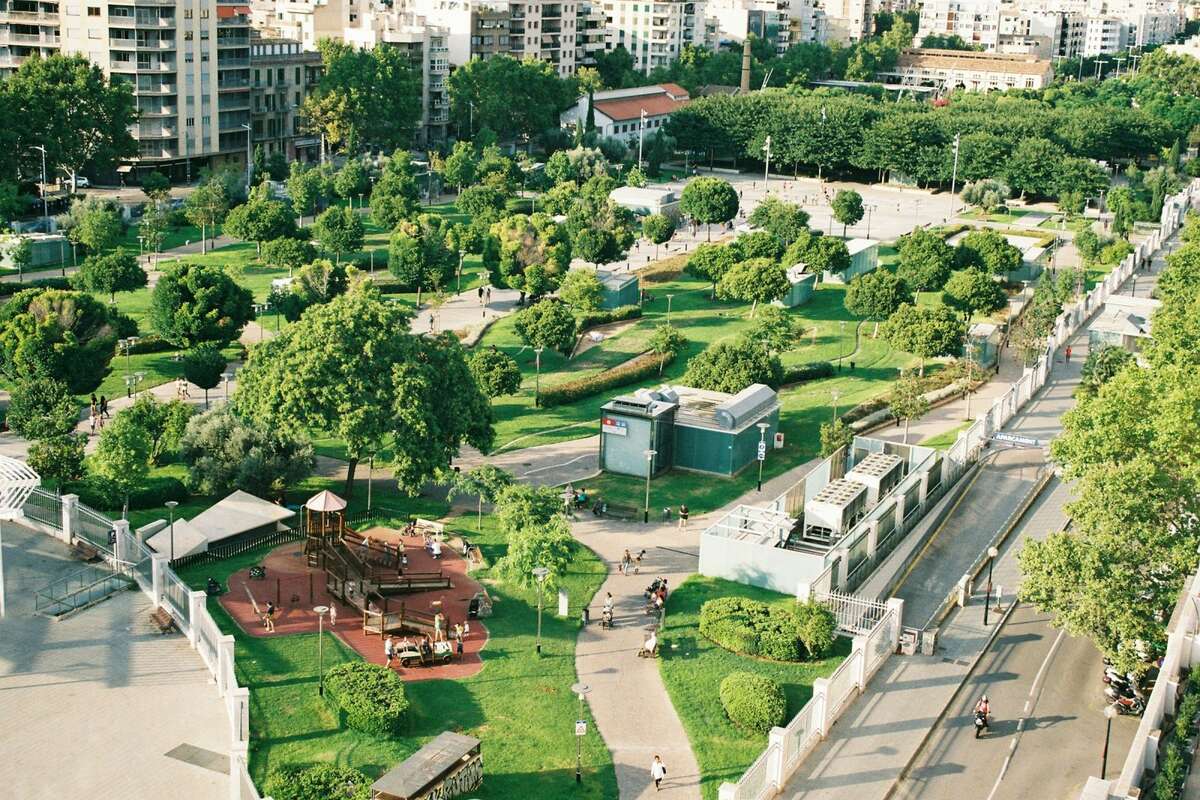

These efforts to keep citizens cool are essential to saving lives, and they can be organized relatively quickly in comparison to the longer-term buildout that’s necessary for cooling our cities naturally. Greening our cities—with more sun-blocking green canopy, less sun-soaking concrete—is a longer-term investment to systematically cool them.

In addition to saving lives, there are additional wins that come with vegetating our cities. Not only will it help draw down and sequester carbon from the atmosphere, which is necessary given last year’s record emissions, but it will also help cities prevent flooding. Warmer air holds more moisture, which leads to heavier downpours. And imperviously paved cities and overwhelmed stormwater drains can’t handle all that water at once. More plants can help by capturing and storing the water, lessening the risk of flooding. A win-win.

With these win-wins, why haven’t cities already gone green to prevent heat deaths and expensive infrastructure-damaging flooding? In many cities there are competing pressures to build and develop green space, but it also takes financial and political capital to increase urban tree canopy.

That’s why the U.S. Forest Service decided to invest the $1 billion from historic climate legislation passed in 2022 for community and urban forestry programs nationwide—with a focus on front-line disadvantaged communities, those most vulnerable to heat.

Expanding access to trees and green space in neighborhoods across America requires this kind of big investment. Of course, the return on that investment is quite high as well—it means lives saved, communities and habitats restored, recreation promoted, public spaces reinvested, and flooding prevented. Public funds for public benefit.

This billion-dollar investment, to be clear, is a big deal. In fact, it’s unprecedented. Now the question is how those resources get implemented across 400 projects in the U.S. Re-granting organizations are trying to figure out how to do it in a way that doesn’t just tackle the heat, flooding, or carbon issues but also zooms out to consider socio-economic factors as well.

For example, the Center for Regenerative Solutions and the Urban Sustainability Directors Network received $28 million from the U.S. Forest Service to do some of this work, and they’re now helping communities across the country adopt nature-based solutions and make them as people-centered as possible.

When any of this green infrastructure goes into a community, local collaboration between municipal and community leaders deciding the “what, where, when, and how” is essential. And if residents are enabled and empowered to take the lead, there’s a greater likelihood that this natural infrastructure is maintained and sustained to provide benefits far into the future.

This is basic stuff that’s consistent across any development agenda but too often neglected, be it in State Department-funded development projects in post-war Ukraine or in green infrastructure projects in post-industrial Cleveland. Funds often flow quickly to stand up a project to show immediate impact. And that pressure from funders often circumvents the very communities we’re trying to serve.

That’s why today’s efforts need to be different. Getting local buy-in for design and implementation is essential. Otherwise, there’s no guarantee that the green will stick around and survive. It’s got to be locally customized. Cities across the country are saying “yes” to this approach, from Albuquerque, Atlanta and Austin, to Baltimore, Boise, and Boulder, to Tacoma and Toledo.

There’s a hunger for more help, which is why the federal billion-dollar investment is just the beginning. While that investment represents a major step, our momentum cannot slow. Congress must do more to expand and create new federal grants for state, local, and Tribal governments as well as for public health systems to develop heat response plans that invest in greening and cooling communities. We have an opportunity to plant the seeds of greater action.

As cities get hotter and wetter, there’s a recognition that local governments can’t manage the heat on their own. Local communities are key to ensuring an equitable response. That’s the preferred power-shared approach anyway. And it’ll increase the likelihood that those billion dollars flower and bear fruit for generations to come.

U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett represents communities from Austin in the U.S. House of Representatives and serves as Ranking Member of the Health Subcommittee on the House Ways & Means Committee. Dr. Michael Shank is the director of engagement at the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance and adjunct faculty at New York University’s Center for Global Affairs.