Historical data show that to date, a reduction in energy availability has mostly affected the US, European countries, Japan, and other advanced economies. I expect this situation to continue as energy limits become more of a problem. Advanced economies will start looking and acting more like today’s less-advanced economies. The world economy will face a bumpy path in a generally downward direction.

In this post, I give an overview of our current predicament. All economies are subject to the laws of physics. We are biologically adapted to needing some cooked foods in our diets. We have also moved away from the equatorial regions, so many of us need heat to keep warm. With a world population of 8 billion, we are a long way from meeting all our energy needs with renewable sources alone.

The world’s fossil fuel supplies are depleting, but politicians cannot tell us the true nature of our predicament. Instead, we are told a “sour grapes” narrative: “We need to move away from fossil fuels to prevent climate change.” What this narrative, in fact, seems to do is shift an ever-greater share of fossil fuels that are available to less-advanced economies. It may also spread out the use of fossil fuels over a somewhat longer period. But there is no evidence that this narrative actually reduces the overall quantity of carbon dioxide emissions. Instead, the more advanced economies are likely to be hit sooner, and harder, than the less advanced economies by the problem of energy limits, pushing them on a bumpy road downward.

[1] Economies tend to collapse because populations rise faster than the resources (particularly energy resources) required to support those populations.

We are dealing with an age-old problem: Humans are able to outsmart other animals, and for this reason, human populations tend to rise except when external conditions are quite adverse.

The necessary steps needed for humans to outsmart other animals began about one million years ago, when pre-humans first learned to control fire. With the controlled use of fire, humans could

- Cook food to make it easier to chew and digest.

- Kill pathogens by cooking food or boiling water.

- Scare away wild animals.

- Keep warm in colder climates.

- Eat a more varied diet, with more protein. Primates eat mostly plants; humans are omnivores.

- Spend less time chewing food and more time working on crafts.

- Indirectly, the shape of the human body could change. Teeth, jaws, and guts became smaller; brains became larger.

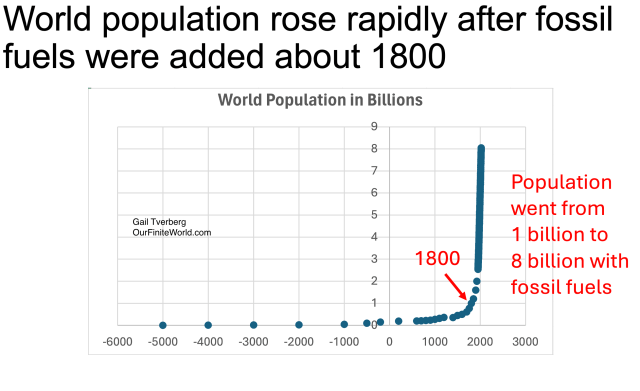

After 1800, when fossil fuel consumption began to grow, human population started to rise at an unprecedented rate. With coal, it was easier to make metal tools, including cooking utensils, in reasonable abundance. While it is possible to smelt some metals using charcoal (made by partially burning hardwood, then cutting off the air flow), doing so tends to lead to deforestation if more than a small quantity of metal is made.

Figure 1 indicates that population had started rising well before 1800. Thomas Malthus wrote about the difficulty of increasing food supply as rapidly as population in 1798. The problem of rising population exceeding resources is an age-old problem.

[2] The physics reason for the limited lifespan of economies is not understood by many people.

In many ways, economies are like humans and hurricanes. In physics terms, all three are dissipative structures. They need to “dissipate” energy of the right kinds to remain “alive.” All dissipative structures are temporary in nature. No dissipative structure, including an economy, can stay away from a cold, dead state permanently. Usually, dissipative structures are replaced by slightly different dissipative structures. This process allows long-term adaptation to changing conditions.

Dissipative structures are self-organizing. They seem to act on their own. Our human leaders may believe they are completely in charge, but this is not really the case. The economy seems to choose its own course, just as humans and hurricanes do.

The energy products that humans require are food products, some of which need to be cooked. The energy products that economies require are of many kinds, including solar energy to grow crops, human energy to tend the crops, and many types of fuels including firewood, coal, oil, and natural gas. Electricity is a carrier of energy produced by other means. Much modern equipment uses electricity, but trying to transition to an all-electric economy is fraught with peril.

In today’s world, energy products of many types act to leverage human labor. As far as I can see, growing fossil fuel consumption is the primary reason why human productivity grows.

Oil is especially important in farming and transportation. Coal and natural gas are important in steel and concrete manufacturing, and in providing heat for many processes. Years ago, oil was burned for electricity, but today coal and natural gas are the fuels typically burned to provide electricity. Fossil fuels are also important for their chemical properties in many different goods, including in plastics, fabrics, drugs, herbicides, and pesticides.

Using renewable energy, alone, sounds like a good idea, but it is not possible in practice. Forests were the major source of energy to support the economy before the advent for fossil fuels, but deforestation became a problem long before 1800. The world’s population, even at one billion, was too high to sustain using biologically renewable sources alone.

At a population of around 8 billion today, there is no way that wood, and products derived from wood, can support the energy needs of today’s population. Doing so would be like humans trying to live on a 250 calorie a day diet instead of a 2000 calorie per day diet.

What are referred to as modern renewables (hydroelectric power and electricity from wind turbines and solar panels) are really extensions of the fossil fuel system. These devices can only be made and repaired using fossil fuels. In addition, today’s electrical transmission system is only possible because of fossil fuels.

[3] Advanced Economies tend to be “advanced” because of the large amounts of fossil fuels they use to leverage the labor of their citizens.

In my analysis, I use the term “Advanced Economies” to mean countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). “Other than Advanced Economies” are then equivalent to non-OECD countries. I use this terminology because it better describes the reason why these two groupings have such different indications. Also, it is not intuitive that such a difference underlies these two groupings.

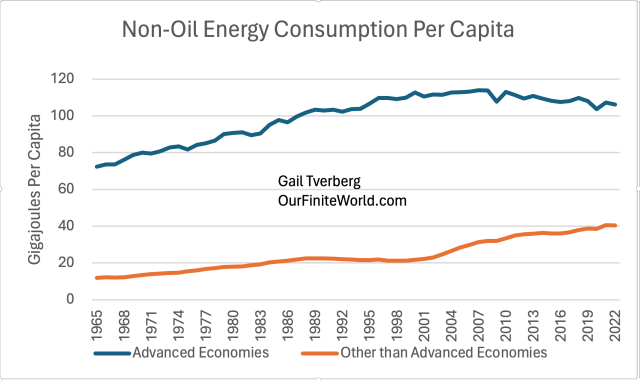

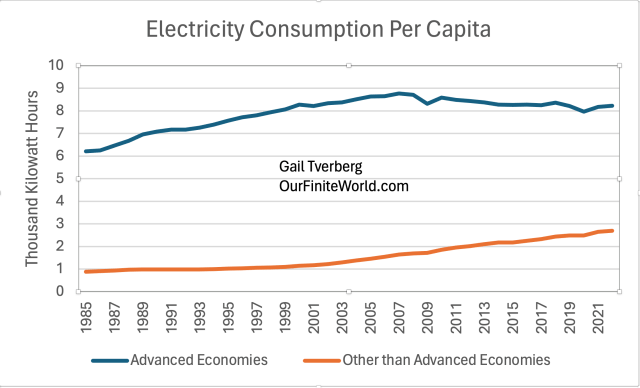

My analysis shows that energy consumption per capita is much higher in Advanced Economies than in Other than Advanced Economies, for all three energy charts shown: oil (Figure 2), all other kinds of energy grouped together (including renewables) (Figure 3), and electricity (Figure 4).

It is clear from these charts that the general trend in energy consumption per capita in recent years is down in Advanced Economies, while the general trend in energy consumption per capita is up for Other than Advanced Economies. To me, this means that the self-organizing economic system favors Other than Advanced Economies in the bidding for scarce energy resources.

One interpretation might be that Advanced Economies are using energy products in a wasteful way, compared to Other than Advanced Economies. The self-organizing world economy in some sense tries to maintain itself, even if some less efficient parts need to be squeezed down or out.

The narrative we hear from politicians and others is that Advanced Economies are moving away from fossil fuels to prevent climate change. This seems to be the narrative the self-organizing economy provides to people who live in Advanced Economies. I will discuss how this occurs, and its lack of success in reducing overall carbon emissions, in Section [5] of this post.

[4] Figures 2, 3, and 4 (above) reflect the impacts of several events leading to a squeezing down of energy consumption per capita.

The following are some events that indirectly squeezed back the energy consumption growth of Advanced Economies:

- Oil prices spiked in 1973-1974, leading to recession, indirectly in response to US first hitting oil limits in 1970.

- Severe recession, in response to Paul Volker’s increase in interest rates in the 1977 to 1980 timeframe.

- China was added to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in December 2001, allowing it to ramp up its manufacturing using coal. This primarily represented an increase in energy consumption by Other than Advanced Economies. At the same time, it removed a great deal of manufacturing from Advanced Economies, so their energy consumption should have been reduced.

- The Great Recession of 2007-2009.

- The 2020 pandemic and its response.

A person can see the impacts that these changes have had on per capita oil consumption (Figure 2), energy other than oil consumption (Figure 3), and electricity consumption (Figure 4), by looking for these dates in the charts, and noticing what changes in trends took place.

Figure 2 shows that there were very large cutbacks in oil consumption per capita in Advanced Economies, prior to 1983. In this early time frame, cutbacks in oil usage were fairly easy to obtain. Some examples include:

- US-made cars in the early 1970s were large and fuel inefficient, but Japan and Europe were already making smaller vehicles. By importing smaller vehicles, and making smaller ones in the US, major savings could take place in oil usage.

- Some oil was being burned to generate electricity. Such generation could be changed to natural gas, coal or nuclear.

- Home heating often used oil. Such heating could be replaced with heat based on natural gas or electricity.

With respect to China joining the WTO in 2001, and this action leading to much greater consumption of coal for manufacturing, these actions ironically followed the Kyoto Protocol of 1997. According to this protocol, Advanced Economies indicated that they planned to reduce their own carbon dioxide emissions. They did this by outsourcing manufacturing to countries not affected by the Kyoto Protocol. These countries were poor countries, including China and India.

It is possible to see the effect of this ramp up in energy consumption by Other than Advanced Economies in both Figures 3 and 4, starting about 2002. In theory, energy consumption per capita by Advanced Economies should have fallen at the same time, but it didn’t. This is one reason why carbon dioxide per capita started rising rapidly in 2002 (Figure 6).

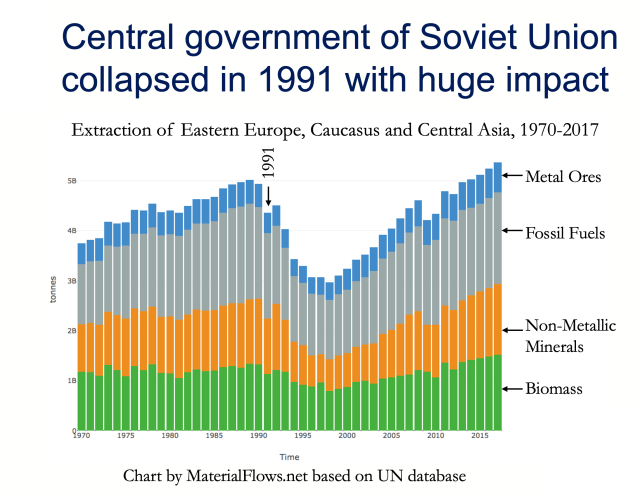

One squeezing-out event disproportionately affected “Other than Advanced Economies.” This was the collapse of the central government of the Soviet Union in 1991. All the countries involved in the Soviet Bloc were affected. Manufacturing in these countries dropped at about this time, as did all types of energy production and consumption. This can be seen as a small dip in the “Other than Advanced Economies” line between 1991 and 2001 in Figures 2 and 3.

While the Soviet Union had plenty of fossil fuels, the world oil price was very low (indicating oversupply). As a result, the country was not getting enough revenue for reinvestment in new oil fields and to repay debt and meet other obligations. The world’s self-organizing economy squeezed out the least efficient oil producer, which was the Soviet Union. The fact that the economy was Communist, and thus allocated resources and rewards in a strange way, may have also played a role in the collapse.

Figure 5 shows the widespread impact of the collapse of the central government of the Soviet Union.

[5] The narrative, “We are moving away from fossil fuels to prevent climate change,” seems to be self-organized by the dissipative structures underlying Advanced Economies.

The real story is that fossil fuels are moving away from us. Somehow, we must adapt, very quickly, to this disastrous situation. But this is not a story that politicians can tell their constituents, or that universities can tell their students who are studying for future job opportunities. Instead, they need a “best case” scenario: There is perhaps something we can do; we can transition away from fossil fuel use quickly.

It is not possible to explain to the public what is really happening. Instead, a “Sour Grapes” scenario is presented. In this narrative, the current economy can continue, much as today, without fossil fuels. (This is clearly nonsense in a physics-based economy, with today’s “renewables.”) We should move away from fossil fuels because they add too much carbon dioxide to the atmosphere.

It should be noted that this “we-can-move-from-fuels narrative” has been spearheaded by the International Energy Association (IEA), which is an arm of the OECD. (I mentioned earlier that I have equated OECD with Advanced Economies). Countries included in “Other than Advanced Economies,” at best, claim lip service to limiting carbon emissions. Their primary interest is in raising the living standards of their populations. To a significant extent, the fossil fuels that Advanced Economies decide not to use can be used by Other than Advanced Economies.

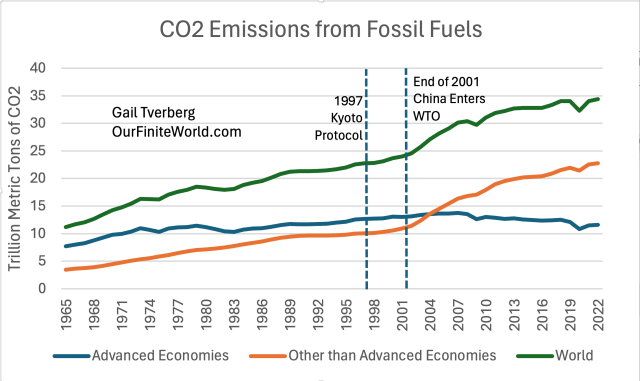

Figure 6 below shows that the efforts of IEA/OECD to reduce carbon dioxide emissions have worked in precisely the wrong direction, on a world basis. Preliminary data for 2023 shows that world carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels rose by another 1.1%.

The plan to reduce carbon emissions for participating countries was first specified in the Kyoto Protocol of 1997. The World Trade Organization (WTO) began a little earlier than this, in 1995. The purpose of the WTO was to increase world trade and thus the total goods and services the world economy was able to produce. In some sense, the Kyoto Protocol and the WTO had opposite objectives. The only way more goods and services could be produced was by using more fossil fuels.

Figure 6 shows that fossil fuel emissions increased sharply after China joined the WTO in December 2001. China was able to ramp up its industrial production using its very large coal resources. It is not clear that the Kyoto Protocol did much besides encouraging Advanced Economies to move their manufacturing elsewhere. This paved the way for the industrialization of Other than Advanced Economies, mainly by burning coal. At the same time, the Advanced Economies have been turned into service economies that are dependent upon Other than Advanced Economies for manufactured goods of nearly all kinds.

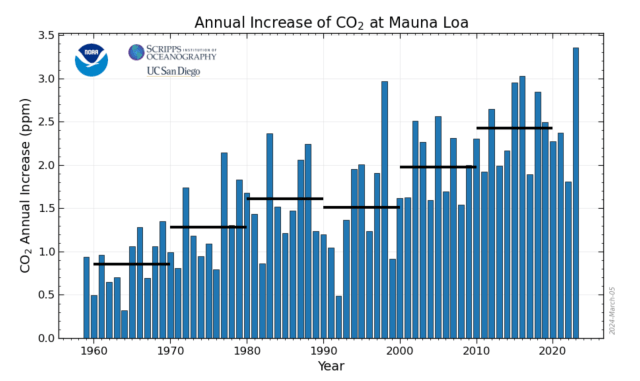

NASA says that when carbon dioxide is added to the atmosphere, it stays around for 300 to 1000 years. NASA also reports that the increase in atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa was the highest ever in 2023.

The increases shown on Figure 7 are relative to a large base. As percentages, they range from about 0.2% per year in the earliest periods to about 0.6% per year in recent periods.

In summary, whatever the Advanced Economies are doing to restrict emissions still leaves the world’s emissions from fossil fuels, as well as atmospheric emissions, rising fairly rapidly. Given the self-organizing nature of the world economy, I am doubtful that there is anything we humans can do to fix this situations. The people in Other than Advanced Economies need fossil fuels to feed their growing populations, and to give them the basic necessities of life.

[6] Figure 8 shows the path that Advanced Economies seem to be following.

In my opinion, with less oil and other energy per capita, Advanced Economies have become increasingly hollowed out, with more of their manufacturing transferred to Other than Advanced Economies.

In Figure 8, economies start out small, with growing resources per capita. As resource limits are hit, economic growth slows, and well-paying jobs become harder to get, especially for young people. In agricultural economies, the problem is that farms need to get smaller and smaller if there are too many surviving children, and they all want to be farmers. Clearly, too small a farm will not feed a growing family.

In the case of Advanced Economies, they become hollowed out because they find themselves increasingly dependent on imported goods and services. Other than Advanced Economies, with lower wages, less overhead for heating/cooling homes and health care, and lower energy costs, can produce manufactured goods more cheaply than Advanced Economies.

As Advanced Economies lose manufacturing and industries such as mining, they also become more dependent on debt and government programs. This added debt becomes increasingly hard to service, especially when interest rates rise.

Advanced Economies become particularly vulnerable to adverse changes because they have lost the ability to manufacture many of the goods required for everyday living. In fact, it becomes a problem even to fight wars, because many of the materials required to make weapons need to be imported from overseas.

Over the long-term, collapse may occur, but this collapse is unlikely to occur all at once. Instead, it can be expected to be what is sometimes called catabolic collapse, which takes place in steps. Parts of the economy will hold together as long as there are resources to support those parts. Future changes in Advanced Economies can be thought of as being somewhat like the changes to the economy in 2020 (indirectly related to Covid-19), but “on steroids.”

[7] Some of the kinds of changes that can be expected.

We don’t know precisely what changes to economies lie ahead, but these are some ideas of things might happen to Advanced Economies before a full collapse.

[a] Loss of the “hegemony” of the US. In the years since World War II, the US has taken on the role of the world’s policeman. But the US has been having increased difficulties when it comes to actually winning the wars it gets involved in. It is very difficult for the US to make weapons in quantity when large parts of the supply lines involve other countries. Also, today’s weapons aren’t necessarily suited to dealing with today’s attacks, such as by the Houthi Group in the Red Sea.

Changes may already be starting. We hear about Victoria Nuland’s recent abrupt retirement as Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs. She is described as “a determined advocate of tough policies toward Vladimir Putin.” She is being replaced, at least temporarily, by John Bass, who oversaw the US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

[b] Loss of the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. The US has had a financial advantage, as long as all other countries had to first change their currencies to the US dollar, in order to trade among themselves. This arrangement allowed the US to import more than it exported, year after year. It also allowed the US to use sanctions against other countries to cut off their trading abilities.

Changes already seem to be starting to reduce the role of the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. In May 2023, Reuters reported, Vast China-Russia resources trade shifts to yuan from dollars in Ukraine fallout. Also, the BRICS nations have been working on an alternative currency, as a possible replacement currency for trading. And, of course, there are all kinds of cryptocurrencies that might be expected to facilitate purchases across borders.

[c] Major loss of trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific freight trade and passenger travel. An easy way to save oil would be to stop shipping goods as far as producers do today. Unfortunately, quite a bit of what we purchase in the US has supply lines that start in China.

Without trans-Atlantic or trans-Pacific supply lines, many goods the US depends upon would disappear from shelves in the US. Computers and telephones, for example, might become unavailable, as would many drugs, especially low-cost drugs. Even high-quality steel drilling pipes, used for oil extraction, might become difficult to obtain.

It is not clear how the US would deal with this issue. It is likely that the economy would need to find substitutes or get along without whatever is lost due to broken supply lines.

[d] Significant defaults on financial promises of all kinds, including bonds, loans made by banks, rental contracts, and derivatives. Ultimately, a decline in asset prices seems likely.

The amount of debt and financial products used in Advanced Economies is at record levels. If a major recession occurs, debt defaults and derivative failures can be expected. Some renters will default on their contracts. Bank failures can be expected, as well.

Politicians will not want to throw people out of their homes; they likely won’t even want to take their automobiles away. Instead, it is likely to be those who are counting on wealth from long-term promises made by poor people who lose out. For example, some of today’s wealthy people may find their wealth disappears when renters cannot make payments on their apartments or farms.

If bank lending starts becoming a problem, peer-to-peer lending may start to take a larger role. This would seem to be the equivalent of replacing taxis by Ubers and replacing hotels by private citizens renting out rooms. The total amount of debt available will fall. With less debt available, asset prices of all kinds will tend to fall.

[e] Much more interest in reusing old buildings, old furnishings, and old clothes. Also, making use of salvaged parts of buildings and spare parts from old mechanical equipment, including automobiles.

If the making goods that depend on overseas supply lines becomes difficult, substitutes such as previously used goods will likely be in demand. For example, we may go back to sourcing replacement parts from automobiles parked in junk yards.

Local entrepreneurs will find ways to make use of whatever goods can be used again. Such work may be a new source of jobs.

[8] We are likely to have a bumpy road ahead. Energy and the economy work together in very strange ways. While the path is generally downward for the world, the part of the world that uses energy very sparingly has a better chance of maintaining and even increasing its standard of living.

Our self-organizing economy puts together all kinds of narratives that lead us to believe that we certainly know the only path forward (and, in fact, we can control the economy to follow this path). But the system doesn’t behave the way we think it does. We assume that if we stop using fossil fuels, it will reduce the world’s use of fossil fuels. For example, stopping the Keystone XL Pipeline in 2021 was considered a great environmental victory. But now we read, Canada could lead the world in oil production growth in 2024.

This extra production will likely be going west to China and to other Asian destinations. Canada’s expanded Trans Mountain Pipeline will open in April 2024, adding 590,000 barrels per day of export capacity. If US protestors don’t want Canada’s “tar sands,” many people in China and other poor countries certainly want it. The very heavy oil that Canada produces is ideal for producing diesel, which the world economy is short of.

Likewise, the US may have bypassed easily mineable coal in its rush to shift electricity generation to natural gas. If the US cannot maintain its military strength, this coal becomes a valuable resource for any military power that wants to test its strength against the US. This available coal makes war against the US by other powers more likely.

We don’t know what is ahead. The “truths” that we are sure we know, aren’t necessarily true. The world economy seems likely to head downward slowly, but this general downward movement will be in spurts. Trying to predict exactly what is ahead is close to impossible.