- Trucking is booming in Alaska compared to the Lower 48 where a massive freight recession has resulted in recent bankruptcies and layoffs.

- A chronic driver shortage has boosted pay, with full-time truck drivers in Alaska able to earn up to $175,000 annually.

- The increase in truck traffic related to new oil production and gold mining is causing some backlash from lawmakers.

The Lower 48 has experienced a massive freight recession over the past few years, but the opposite is occurring in one place in the United States: Alaska.

With various North Slope oil production projects just ramping up, the years ahead look very promising for trucking in Alaska.

“This is probably the best trucking has been in Alaska since 2000,” said Jeremy Miller, vice president of operations at Anchorage-based Carlile Transportation Systems, who has been with Carlile since 1998.

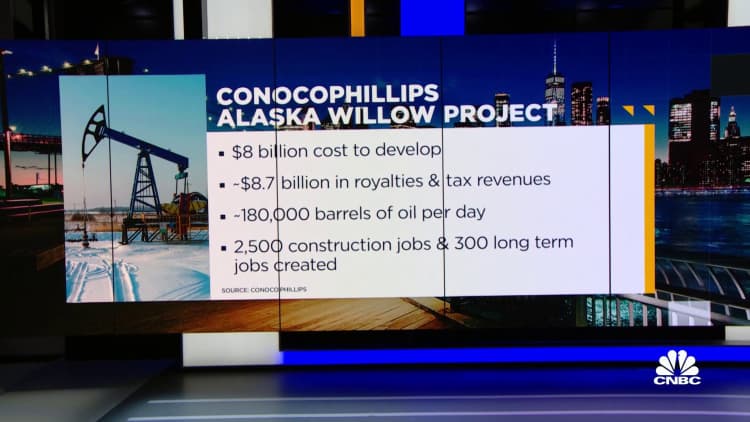

Among the new North Slope activities is the ConocoPhillips Willow Project, which the Biden administration approved last year. Willow had been delayed and mired in controversy over its potential environmental impact on pristine Arctic lands, but now that work has been greenlighted, construction of oil pads and camps has commenced. Willow is expected to generate 600 million barrels of oil total, or 180,000 barrels a day at its peak, according to ConocoPhillips.

Meanwhile, the Pikka oil project by Australian company Santos is also taking shape on the North Slope, 50 miles west of Deadhorse. Infrastructure improvements are being built now in anticipation of operations beginning in 2026, which could produce 150,000 barrels of oil per day the company says.

According to a report by the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, both projects combined will increase the state’s oil output by 30% within 10 years. All of that oil infrastructure will need continued trucking support.

For Miller, this juxtaposition between freight markets is not a rarity. Trucking in Alaska has often experienced the opposite of conditions in the Lower 48. But 2024, and likely beyond, is a super-charged different.

For trucking company Alaska West Express, 2015 was the peak year in recent memory. But the volume for 2024 is approaching 2015, and Matt Jolly, president of Alaska West Express, expects record numbers ahead.

“The next five years should see record truckload counts,” Jolly said.

During the busy ice road season, which generally runs at through at least April, Alaska West Express dispatches 15-20 trucks per day north to Prudhoe Bay along the Dalton Highway.

“It’s a day up and a day back, so with northbound and southbound movement, we have between 30 and 40 trucks on the road at any given time,” Jolly said. Roads able to support heavy trucks, made from flattening down ice without harming tundra, are key to connecting the Dalton Highway’s terminus with the oil fields.

Alaska West specializes in chemical and dry commodity hauling in 5-axle tankers and bulkers with payloads up to 67,500 pounds. Jolly says they haul products ranging from diesel, avgas, LVT, corrosion inhibitors, scale inhibitors, glycols, barium sulfate, and cement on the bulk side. They also move heavy machinery, pipe spools, and oversized modules.

“It is a boom time for trucking companies here,” said Joe Michel, president of the Alaska Trucking Association, citing the multiple projects on the North Slope creating plenty of work for freight companies and a chronic need for drivers.

“If you are a qualified driver, someone will pick you up quickly,” Michel said.

Miller says the annual pay for a driver who doesn’t mind the stretches of isolation and Arctic challenges can be $180,000. But even drivers who want to haul locally in Anchorage and don’t want to be gone nights can still make $75,000 annually.

Most of the North Slope oil infrastructure (supplies, machinery, parts) is supplied by trucks that have to traverse the 414-mile Dalton Highway (Alaska Route 11).

The Dalton Highway drive is not for the faint of heart. Much of the “trucking season,” when the ice roads open up in the tundra, is done in 24-hour pitch blackness. Ice, fatigue, and meandering moose are a constant danger. Alaska is the land of the midnight sun in summer but also noon darkness in winter. Drivers have to negotiate the fickle mostly gravel Dalton in the dark. And you won’t find a McDonald’s or Wawa anywhere along the route. Still, it is traveled by hundreds of trucks daily during the busy season.

Michel said a “truckers code” and camaraderie develop with the drivers, forming a close-knit community.

“The truckers know one another,” Michel said, adding that certain turns along the Dalton have names, hills have names, and trucks carrying cargo, which are almost always northbound trucks, get the preferential treatment. Truckers communicate by CB.

“They take care of their own, the camaraderie is very impressive,” Michel said.

While trucking companies in the Lower 48 do almost anything to avoid empty miles, doing business on the North Slope means that most trucks heading southbound on the Dalton are not carrying any cargo.

“Empty miles are a very large part of doing business on the slope. There are limited opportunities for backhaul freight,” Jolly said.

Fairbanks, population 32,000, is the logistical hub and staging area for all the activities.

“We are having a reflowering on the North Slope,” said Jomo Stewart, president and CEO of Fairbanks Economic Development Corp., and he added that a lot of the projects are truck-dependent.

But the North Slope isn’t the only place in Alaska experiencing a trucking boom. New mining activity in central Alaska is also putting more rigs on the road, rigs that eventually end up in Fairbanks. And all the trucks have some, including some of the most powerful names in Alaskan politics, saying “enough.”

The recently established Manh Choh gold mine in Tetlin, operated by Kinross Alaska, will begin trucking ore over 200 miles from Tetlin through Fairbanks to the company’s processing facility north of the city. Once the Manh Choh mine is running at full capacity, 95-foot, 16-axel rigs loaded down with ore weighing 165,000 pounds will begin making their journeys. The trucks could be making upwards of 60 trips a day back and forth. The lumbering trucks will pass through popular tourist towns and through Fairbanks.

“We have always had a very robust trucking sector as a logistics center, but it has become quite contentious. These are big trucks running on a 24-hour day cycle to feed the mill,” Stewart says, adding that some of the reaction to it puts trucking’s robust recovery at risk.

Stewart says the biggest risk is a bill that lawmakers have introduced that will require trucks over 140,000 pounds to obtain a permit. The permit fee would go to road maintenance which opponents of the ore trucking say will be needed because of wear on the roads.

Stewart fears legislation could have unintended consequences for truck-dependent Fairbanks.

“If a truck is now a bad thing, there is a whole range of activities that you are potentially putting at risk. Food gets here on trucks, and natural gas gets here on trucks. People are happy for the increased economic activity, but some don’t like the idea of this volume of trucks going through town,” Stewart said.

Alaska State Senator Scott Kawasaki (D-Fairbanks) and State Representative Ashley Carrick (D-Fairbanks) have both introduced bills to require permits.

Kawasaki says curtailing trucking isn’t the bill’s intent.

“This bill really focuses on the maintenance issue,” Kawaski said, citing Alaska Department of Transportation studies that show $40 million in road maintenance will be needed along the 200-plus miles of highway. And Kawasaki says there is a carve-out for trucks carrying commodities like food and fuel so that increased costs don’t hit consumers the hardest.

Kinross could not be reached by press time, but has vowed to be a safe operator on the roads.

“Anyone familiar with how we operate knows that we operate in the most stringent manner relating to safety as possible, and that is without a doubt our key focus and always will be,” a Kinross spokeswoman told the Anchorage Daily News.

Michel says that the proposed legislation goes too far.

“The bill attacks all aspects of trucking across the whole state of Alaska,” Michel said, saying that the lawmakers have cast a much wider net instead of using a “scalpel” to target possible issues from one project.

Kawasaki says, however, that this bill is at least meant to bring attention to the issue of truck traffic.

“The bill is a discussion point to bring the truckers and public onto the same page,” he said.

Michel says it is unlikely that anything will be done with the bill in the waning days of Alaska’s current legislative session but worries that the issue will now come up each year and that having trucks pay for permits could just cause more trucks because some companies may choose to lower their volume rather than pay for the permit.

“The bill will increase traffic because the demand will still be there,” Michel said.