End of Net Metering in Hawaii Shifted Solar Installations from Residential to Commercial. California Can Expect the Same

The Hawaii PUC was required to leave net-metering in place until solar installations exceeded one-half of one-percent of customer load. It actually left NEM in place much longer – until solar penetration was ten times that high. But, in 2015, traditional NEM was ended for new solar customers, and replaced with some other options. These have included:

Customer Self Supply (CSS) – Customers can meet their own needs with on-site solar, but are prohibited from any export. This was the initial alternative offered when Hawaiian Electric imposed a moratorium on new solar due to system saturation and emerging voltage control and frequency regulation challenges.

Customer Grid Supply Plus (CGS+) – Systems must include grid support technology to manage grid reliability and allow the utility to remotely monitor system performance, technical compliance and, if necessary, control for grid stability. Customers receive compensation based on avoided costs to the utility, currently about $0.10/kWh in Oahu.

Smart Export: Customers with a renewable system and battery energy storage system have the option to export energy to the grid from 4 p.m. – 9 a.m. Systems must include grid support technology to manage grid reliability and system performance. Customers receive compensation of about $0.15/kWh from 5 PM to 9 AM, and no compensation from 9 AM to 5 PM.

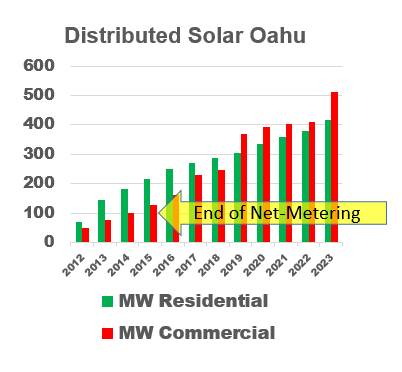

The result of these changes has been a fairly dramatic shift in the types of new solar systems that are installed. Prior to 2015, about 63% of installed solar megawatts on Oahu were residential systems, where customers enjoyed the convenience and economic benefits of net-metering. After 2015, this has shifted to where 66% of new solar is installed on commercial customer premises. Figure 1 shows the sharp shift in new installations from primarily residential in the early years to primarily commercial in the later years.

Source: Hawaiian Electric Company Quarterly Installed Solar Data

The logic for this shift is relatively simple:

First, in 2010, before significant solar penetration, residential customer loads represented about 30% of Hawaiian electric sales. In 2021, this had droped to about 26% of sales, despite significant customer growth. Solar had displaced a fair amount of residential load. But commercial load was and is the vast majority of electricity consumption in Oahu, so the solar customers had plenty of opportunities for solar.

Second, and perhaps most important, solar customers can size their solar system to not exceed their “minimum daytime consumption” so there is no concern about export. Whether it is a Walgreens store with 30 kW of minimum usage or a Walmart store with 300 kW of minimum usage, it is easy to size a system to meet a portion of daytime consumption without being concerned with export to the grid.

Third, with a decline in residential installations due to the end of NEM, solar installers are “hungry” for customers, and have pursued commercial customers.

The result of this is becoming quite evident in aerial photos from Honolulu. From Walmart to Costco, from the Honda dealer to the nursing home complex, solar is increasingly evident on the large flat roofs of commercial business. The installations are simpler (flat roof), more economical (30 kW and 300 kW systems with economies of scale) and more efficient (no tree shading).

However, it is equally evident from aerial photos that there is a lot of remaining potential for rooftop solar (and, in the case of Costco, “shaded parking lot” solar) in Hawaii. Visit Waipahu on Google Maps, and you can see lots of commercial buildings with solar – and an even greater expanse of large flat roofs in retail, warehouse, and office buildings without solar (yet).

Perhaps the most striking is the campus of Leeward Community College, which is Hawaii’s first “net-zero” carbon emissions community college.

Leeward Community College, Public Domain Photo

This is the first, but definitely not the last. Under a partnership between UH, Johnson Controls and Hawaiian Electric Industries subsidiary Pacific Current, four other UH campuses—UH Maui College, Honolulu CC, Kapiʻolani CC and Windward CC—will soon be reducing their fossil fuel consumption by a range of 70 to 98 percent.

What Does This Tell Us About California?

The California PUC has ended traditional NEM, and new solar customers are served under the “NEM3” tariff, which has dramatically lower credit for backfeed than the price for utility-supplied power. It is based on a calculation of “marginal cost” for each time period, and the solar day has become (as in Hawaii) the low-cost period, so the credit for solar backfeed is quite low.

California ALSO has a majority of electricity consumption in the commercial sector, but until now, a majority of the installed solar capacity in the residential sector.

California Solar Installations as of 2023

Residential: 10,466 MW

Non-Residential: 4,358 MW

https://www.californiadgstats.ca.gov/charts/

The Commercial sector need not be terribly concerned about the end of NEM, because systems can be sized to serve only on-site requirements. For the major utilities, Southern California Edison, San Diego Gas and Electric, and Pacific Gas and Electric, residential loads represent only about one-third of total sales. As in Hawaii, the solar installers are seeing diminished interest from residential customers, and will likely redeploy their sales efforts to the commercial sector. A Walgreen’s store might install a 30 kW system, while a Walmart would install a 300 kW system. Each would be sized so that during the day, 90% of usage might be served with solar — but no kWh will flow back to the utility. This is not an optimal deployment of solar from a societal perspective, but will make sense for the building owner and electric billpayer.

And the opportunities are huge. The University of California system alone has millions of square feet of flat roof area, as do major retailers like Walmart, Costco, Kroger, and Albertson’s. Thousands of large commercial rooftops await the investment that today’s California electricity prices invite. It is inevitable that solar installers will shift their focus on this underserved market.

Commercial customers do pay a three-part tariff, with separately metered demand and energy consumption. This means that without battery installation or load management efforts, they will likely NOT reduce their demand charges, which form about one-third of the total electric bill. But the energy component of the bill is more than enough to make solar a cost-effective investment. For PG&E, the A-1 (small commercial) off-peak rate is over $0.40/kWh, and for the larger demand-metered A-10 customers, the off-peak energy rate is over $.25/kWh (in addition to a hefty demand charge). Lazard estimates the cost of commercial solar at $.03 – $.18 per kWh depending on system size and eligibility for federal tax incentives, far below the off-peak energy price for commercial customers.

Think about this time the next time you fly into a major airport. Look out the window, and what do you see: millions of square feet of flat roof buildings, retail, warehouse, and office. How many of them have solar installed? How many of them pay electric bills?

I will confidently predict that over the next two years (as the backlog of residential solar customers grandfathered under NEM2 is completed) that California will see a rapid shift of solar installations into the commercial sector.