- Saudi state-controlled Aramco suspended its capacity expansion plans because of the green transition, Saudi energy minister Abdulaziz bin Salman said Monday.

- “I think we postponed this [Aramco capacity] investment simply because … we’re transitioning. And transitioning means that even our oil company, which used to be an oil company, became a hydrocarbon company. Now it’s becoming an energy company,” the Saudi minister said.

- “Energy security in the 70s, and 80s and 90s was more dependent on oil. Now, you get what happened last year … It was gas. The future problem on energy security, it will not be oil. It will be renewables. And the materials, and the mines,” he stressed.

Saudi’s state-controlled oil giant Aramco suspended its capacity expansion plans because of the green transition, Energy Minister Abdulaziz bin Salman said Monday, stressing that the future of energy security lies with renewables.

“I think we postponed this [Aramco capacity] investment simply because … we’re transitioning. And transitioning means that even our oil company, which used to be an oil company, became a hydrocarbon company. Now it’s becoming an energy company,” the Saudi prince said during a question and answer panel at the International Petroleum Technology Conference in Dhahran, noting that Aramco has investments in oil, gas, petrochemicals and renewables.

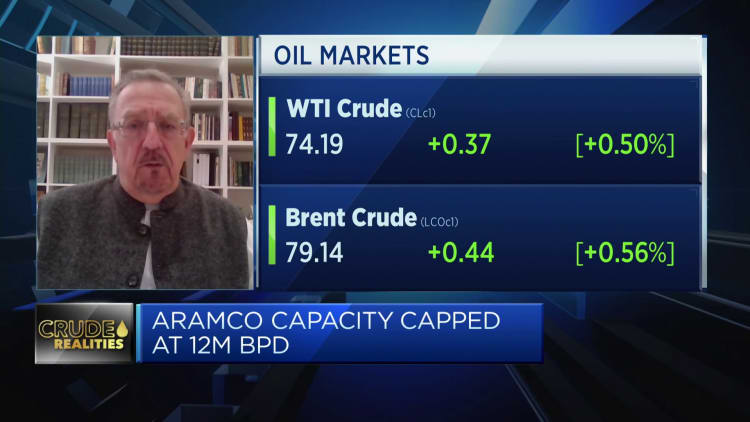

On Jan. 30, the Saudi energy ministry surprised the markets with a directive instructing the Saudi majority-owned Aramco, which went public in 2019, to stop plans to increase its maximum crude production capacity from 12 million barrels per day to 13 million barrels per day by 2027. The ministry did not disclose the reason behind its decision at the time, sparking questions over potential Saudi concerns over the future of oil demand amid a progressing energy transition.

The Saudi energy minister on Monday qualified the decision was not made hastily and was the product of a continuous review of market conditions.

“We are in [a] continuous mode of reviewing and reviewing and reviewing, simply because you have to view the realities [of the market],” he said.

Oil prices have spasmed through waves of volatility in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, weighed by lower-than-expected recoveries in Chinese demand and inflationary pressures. The global movement to decarbonize and stave off a climate crisis has redirected energy companies away from long-term fossil fuel projects in favor of greener investment pastures — and may redefine the outlook for energy security, Abdulaziz bin Salman signaled on Monday.

“Energy security in the 70s, and 80s and 90s was more dependent on oil. Now, you get what happened last year … It was gas. The future problem on energy security, it will not be oil. It will be renewables. And the materials, and the mines,” he stressed, noting that there is still a “huge cushion” of spare capacity available in the event of an emergency shortage. Previously, such supply shocks have struck by way of sanctions or attacks against oil infrastructure worldwide.

“Why should we be the last country to hold energy capacity, or emergency capacity, when it is not appreciated? And when it is not recognized?” the Saudi energy minister said. “Energy security is not just the responsibility of Saudi Arabia. It’s the responsibility of all energy producers and energy ministries,”

Notably, spare capacity has also long served as a diplomatic instrument in the Saudi-led Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, shaping the odds of victory in the fleeting one-month price war between Riyadh and Moscow in 2020.

Saudi Arabia and its OPEC allies have long championed a combined energy transition strategy that utilizes fossil fuel resources until such a time that renewable supplies are available to fully cover global requirements, downplaying concerns over markets imminently hitting peak old demand. The stance stands in staunch contrast to that of the International Energy Agency, which in a landmark report of 2021 advocated against further investment in new fossil fuel supply projects, if humanity is to combat the climate crisis.

Yet Middle East countries have increasingly attempted to reconcile their image as stalwart fossil fuel producers with their energy transition ambitions, with key OPEC producer the United Arab Emirates hosting last year’s U.N. climate-geared Conference of the Parties (COP).

The world’s largest crude exporter, Saudi Arabia aims to decarbonize by 2060, with Saudi Aramco targeting to reach operational net-zero emissions by 2050. Steered by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 plan, the kingdom has also been grappling with diversifying its economy away from overreliance on fossil fuels.