A Wisconsin bill that would enable third-party-owned community solar has failed to progress this fall as backers had hoped, and time is running out for a hearing to be held before the session ends on Nov. 16.

In a twist on the typical politics of renewable energy, the bill is sponsored by more than a dozen Republican state legislators, and advocates pin its difficulties in part on the opposition of labor unions and their political sway over Democratic lawmakers.

Utility industry organizations and individual utilities including Alliant, MGE and WEC Energy Group oppose the bill, which is not surprising as nationwide utilities often see third-party-owned solar as a threat to their market share.

But the IBEW, the Carpenters union and the Laborers District Council have also been lobbying against the community solar bill, according to the state’s lobbying registry.

The IBEW did not return calls for comment. Local leaders surmise that the labor organizations are influenced by the utilities that employ union workers, and likely concerned that community solar installations would not be built by union workers and could undermine the market for utility-scale, union-built solar farms.

Beata Wierzba, government affairs director for Renew Wisconsin, said that while there are no requirements for community solar to be union-built, the legislation could have benefits for unions.

“With a growing solar market, you need more people to work. Jobs would be available for all,” she said. “If you do get federal funding, there are extra benefits for developers if they provide prevailing wages,” equivalent to union wages.

“But because there’s no labor support on the bill as is, the Democratic legislators have not gotten on board,” she said.

Widespread support

Senate Bill 226’s chief sponsors are Republican Sens. Duey Stroebel, Rachael Cabral-Guevara and Robert Cowles, and its 12 co-sponsors are Republican. The bill is also backed by the Conservative Energy Network and Wisconsin Conservative Energy Forum.

In 2021, Stroebel and Republican state Rep. Timothy Ramthun introduced similar community solar-enabling legislation, but the measure did not pass then nor in 2022.

“What makes this issue so compelling to Republicans is to insert some competition on the grid, and customer-centered innovation,” said Matt Hargarten, vice president of campaigns for the national Coalition for Community Solar Access.

In addition to conservative and clean energy groups, the bill is backed by a growing roster of interests including the Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation, the powerful realtors organization and associations representing grocers, builders and contractors, and retailers. The plumbing fixtures company Kohler, the League of Wisconsin Municipalities and a property taxpayers organization also support the bill.

“It’s not just solar developers against utilities,” Wierzba said. “But because the utilities are opposing it, that carries a lot more weight than some other groups.”

Brandon Scholz, Wisconsin Grocers Association president and CEO, explained that since grocery stores operate on profit margins “as razor thin as the cold cut slices at their deli counters,” staying in business means cutting costs wherever possible. Saving money on energy can be a boon, especially since grocery stores use much energy including to power freezers, signs and parking lot lights.

“As long as grocery stores have been in existence, you didn’t have much flexibility [in energy sourcing]. You sign up with the utility, pay the bill,” Scholz said. “Over the years as alternatives developed in sustainable energy sources, everyone is looking to see what they can do.”

Subscribing to community solar could be a way to cut costs, he said, while also pleasing customers who want more sustainability. Community solar lets a grocery store benefit from solar without the investment and work of installing solar on its own property. Even doing that can be difficult in Wisconsin since there is not legal clarity around third-party ownership of rooftop solar — a financing mechanism that makes solar more viable in many states. (The community solar-enabling bill would not address this dilemma.)

“We’re talking about Wisconsin; things happen here with difficulty,” Scholz said. “We want to encourage the legislature to make things like this accessible and easier for small businesses. In Wisconsin it will be a step at a time because utilities have been here a long time; they’ve invested a lot in their infrastructure. As we move to sustainable energy, rooftop solar, community solar, [and] biodigesters should all be part of our portfolio, and community solar rises to the top pretty quickly.”

Ripple benefits

In an op-ed for the Cap Times, Scholz wrote that “in many ways, grocers are a bellwether for the economic health of our communities.”

A study released by the Coalition for Community Solar Access in June quantified the larger benefits if community solar were allowed in Wisconsin.

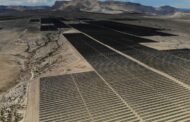

The analysis by Forward Analytics found that 350 5-megawatt community solar facilities statewide would lead to the creation of 34,700 jobs and $2.5 billion in economic activity. That would come from extensive job creation and spending during the construction phase, ongoing lease payments to landowners, and a smaller amount of job creation throughout the installations’ estimated 25-year lifetime.

“One thing that’s different with community solar compared to utility-scale solar is not only is the energy distributed, the economic impacts are distributed,” Hargarten said. “These will be hundreds of small facilities in cities and towns all over the state.”

Hargarten said community solar can be a benefit to farmers, avoiding the difficult tradeoffs and conflicts that often arise when utility-scale solar is sited on farmland. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that about 6.1 acres of land are needed per megawatt of solar, meaning a typical community solar installation could be built on about 30 acres of land.

“Unlike utility-scale which requires hundreds if not thousands of acres, community solar allows farmers to put projects on underperforming parts of their land,” he said. “We’re excited about being able to cohabitate agriculture with solar development.”

Different scales

Utilities can develop community solar and offer subscriptions, but Wierzba noted that it’s typically a low priority for them, including because they can achieve greater economies of scale and profits with large solar farms.

“Technically under the law, the utilities can do community solar — they just won’t, because utility-scale makes more sense” for their business model, she said.

Alliant spokesperson Tony Palese said the utility operates a fully subscribed community solar project in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, with another in the works in Janesville.

Palese said that unlike “private” community solar, Alliant’s community solar “ensures projects will be safely constructed by a local solar developer and local labor to help keep — and grow — jobs in Wisconsin; protects low- and moderate-income families from subsidizing the profits of companies based outside of Wisconsin; provides local governments with shared revenue over the life of the project; and is regulated by the Public Service Commission to protect Wisconsin consumers and our electric grid.”

A March letter from utilities to the legislature argued that the bill would give community solar developers “free access to Wisconsin’s energy system, at no risk to themselves, and shift grid costs to non-participating electric customers.”

“The bill would chiefly benefit the out-of-state Community Solar developers at the expense of the ‘non-subscribing’ customers,” the letter continued. “Meanwhile, the developers would benefit from using Wisconsin’s electric grid with no obligation to maintain service and reliability, to prove the generating asset is necessary or cost effective, or to be a provider of last resort, as Wisconsin’s utilities are required to do.”

Legislation is typically needed to allow third-party-owned community solar installations, including to clarify that they are not acting as utilities or infringing on regulated utilities’ rights.

States along the coasts have such legislation on the books, as do Wisconsin’s neighbors Minnesota and Illinois.

Utility-scale solar — owned and operated by utilities themselves — has been growing in Wisconsin, with at least 28 large utility-scale solar farms operating or being built, according to Renew Wisconsin.

“The utilities are very comfortable with their business model and they’d rather own all the generation capacity in the state, in addition to the distribution capacity in the state,” Hargarten said.

The bill would require utilities to give customers credits on their bills for the amount of energy they receive as subscribers of community solar arrays. The bill would also require financial assurances for the decommissioning of community solar. And it mandates that community solar owners pay property taxes, unlike utility-scale generation, which is taxed on revenue generated.

The bill makes sure that community solar is genuinely available to multiple subscribers by mandating that one subscriber can not account for more than 40% of a project’s output, and at least 60% of that output is accounted for by subscriptions of 40 kilowatts or less.

Wierzba noted that utility-scale solar — which Renew and other clean energy groups support — has faced pushback from Wisconsin farmers and residents concerned about the land use impacts. Community solar can avoid those concerns while providing clean energy benefits, leaving Wierzba and other advocates frustrated that it hasn’t been allowed to develop.

The push for community solar has also seemingly gotten less attention than the fight for legal clarity that would allow the development of third-party-owned rooftop solar. While it is highly unlikely the bill could pass this session, backers hope there might still be a hearing that would raise the issue’s profile heading into the 2024 legislative session when it could be reintroduced.

“Community solar is the third wheel,” Wierzba said, “that doesn’t get the grease.”