Two shocks rippled across America earlier this month. One was economic, when the price of gasoline in California flipped back above US$6 a gallon. The other was meteorological. New York City was inundated by eight inches of rain.

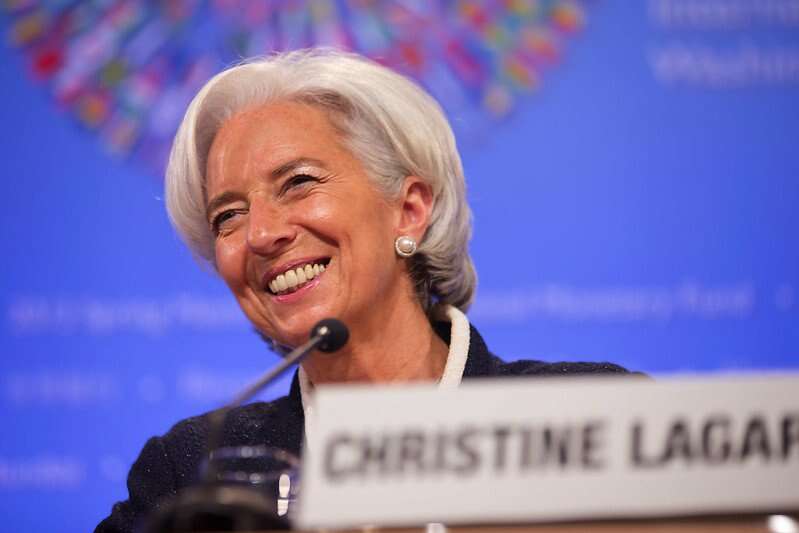

Individually, the two events were just more news noise. But taken together, they provided crucial clues on what Christine Lagarde, the powerful president of the European Central Bank (ECB), says are the critical challenges of a “new” economy we have now entered, Peter McKillop writes for Climate & Capital Media.

How to manage this new economy was why Europe’s leading bankers gathered a couple of weeks ago at a conference organized by the International Energy Agency (IEA), the ECB, and the European Investment Bank (EIB). Their focus was urgent: With the climate crisis escalating, so too are growing fears of a disorderly energy, monetary, and societal transition.

Central bankers have lots of experience with energy and inflation shocks, as anyone old enough to remember gas lines in the 1970s will attest. What is new is an unprecedented environmental crisis requiring a rapid transition away from a fuel source that still powers 80% of all the world’s energy. This is also happening as post-pandemic Europe adjusts to the additional energy supply and price shocks following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

All this pushes central banks into uncharted waters, profoundly challenging their mandate to manage systemic risk, ensure price stability, and keep inflation low. Unlike previous historical monetary and economic shocks, there is no precedent for climate risk. It has not, in bank stress test parlance, been “backtested.” Lagarde and her central bank colleagues may as well be Marco Polo or Jonas Salk.

Read the rest of this opinion piece by Climate & Capital’s Peter McKillop here.