I was recently asked to be a keynote speaker for World Management Conference (WMC 2023) in Patna, India. The academic group that asked me to speak was particularly concerned about Complexity and Sustainability. A PDF copy of the presentation is available at this link.

The primary things I pointed out to the group were the following:

- The slower the growth, the more sustainable an economy is over the moderately long term.

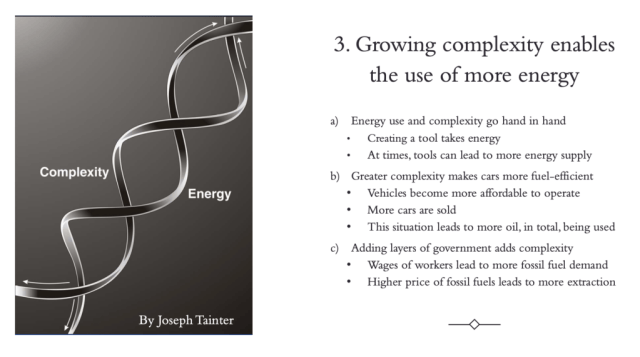

- Energy consumption and the use of complexity tend to rise together.

- Too much complexity can lead to collapse.

- In general, the most “efficient” economies can be expected to do best.

- Over the long term, all economies will collapse.

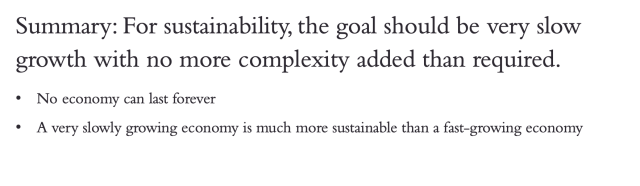

- There have been shifts in which economies get a major share of available energy supplies. Shifting patterns are likely again in the future.

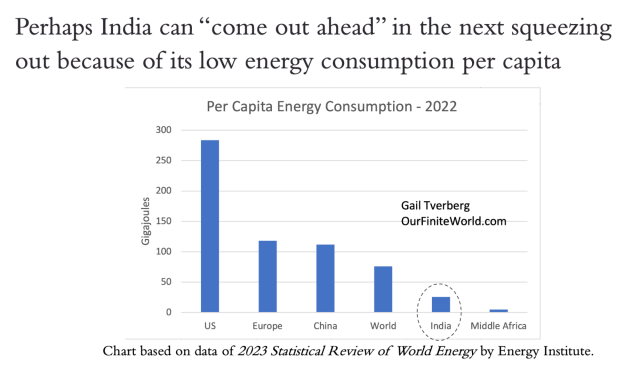

- India may come out ahead in an energy squeeze because its warm climate and conservative culture allow its energy consumption per capita to remain low.

A great deal of my presentation was simply a restatement of the words on the slides, in a slightly different way. So, my comments on the slides will be quite brief.

Of course, after complexity solves problems, population continues to grow, creating a similar problem all over again. This likely leads to the need for even more complexity.

My crude drawing represents the difference between slow growth in population and fast growth in population. Rapid growth is difficult to sustain for very long because arable land and fresh water don’t grow.

There is a similar problem if fossil fuel energy is being used. If growth in consumption is very fast (for example, China’s growth pattern starting in 2002), it becomes impossible to keep up the pattern. There can be two different problems: (a) Running short of fuels, leading to the need for higher-cost extraction and/or imports, and (b) Overpromising in the financial markets, leading to debt defaults and stock market crashes. China seems to be encountering both difficulties, even though its population is falling, rather than growing.

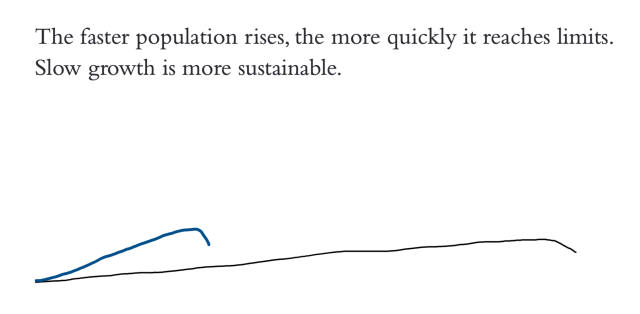

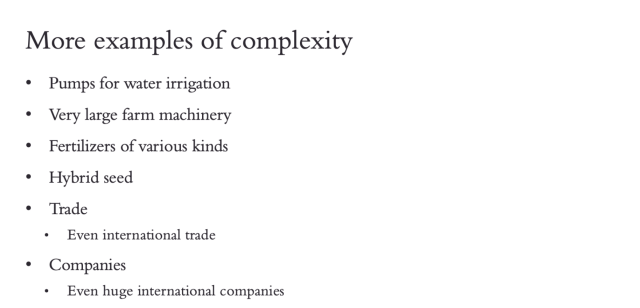

Organizing workers to plant and harvest crops represented a major step up in complexity, relative to hunting and gathering.

A metal tool, such as the one shown on Slide 5, greatly helped the productivity of farmers compared to using a sharpened rock or a piece of wood as a tool, or using only bare hands.

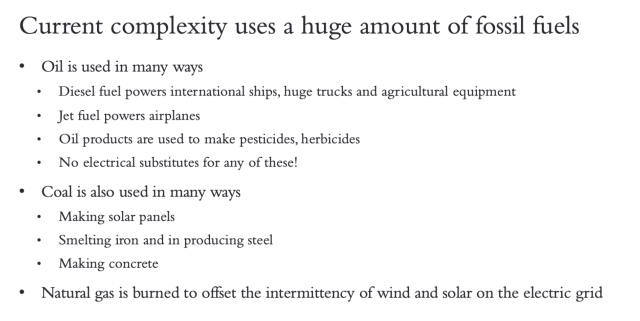

Of course, this list of uses is very incomplete. For example, both coal and natural gas are burned to create electricity.

As an example of a) above, a metal shovel allows more food to be grown. Food is, of course, an energy product that humans eat. Another example would be better drilling approaches that allow more oil to be extracted from a well.

Regarding b), greater complexity makes cars more fuel-efficient cars, making the cars less expensive to operate. This makes them more affordable, so more people can afford to buy them. This is known as Jevons’ Paradox. Although the devices look more efficient, the fact that more people can afford them allows the total amount of fuel used to increase.

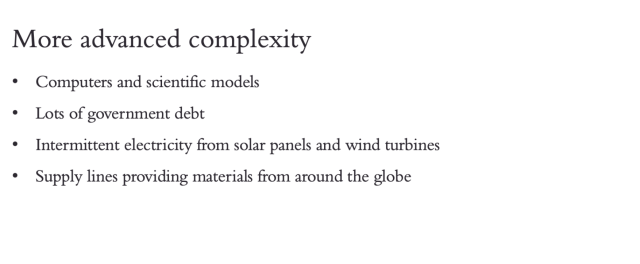

Item c) relates to adding “buying power.” If more people can afford goods because of more government spending or more government debt, the added buying power keeps the demand, and thus the prices, of energy products up higher than they otherwise would be. The higher prices motivate businesses to extract harder-to-access energy resources that might not be profitable to extract if the prices were lower.

We extract the least expensive to extract oil, coal, or natural gas first. Even if our techniques get better, at some point, the price of fossil fuels used in growing and transporting of food becomes unreasonably high. Poor people, especially in low-income countries, have a hard time affording an adequate diet.

Slide 14 shows a chart I put together to try to explain the physics-based way economies are built. In a way, they are built in layers, with new businesses being added at the top, over old businesses, and new laws being added to old sets of laws. New human customers are added, too, and some die or move away.

Every action that contributes to GDP requires energy of some kind. It could be human energy powered by food, or human energy plus fossil fuel powered energy. Moving a truck or train requires energy. Even moving electrons, as in heating food or transferring electrons within transmission lines, takes energy.

One thing that keeps the system in balance is the fact that many of the consumers are also employees. If wages are not high enough (particularly for the poorer members of the economy), it becomes increasingly difficult for them to afford the basic goods and services that they need for living. Of course, changing interest rates or the availability of credit also affects the affordability of goods and services.

Early in the life of the economy, both energy consumption and complexity rise, as depicted in The Energy-Complexity Spiral by Joseph Tainter, illustrated on Slide 12,

At some stage, the economy reaches a point of too much wage and wealth disparity. Poor people cannot afford the necessities of life. Riots by poor people become common, as they did about 2018 and 2019, indirectly because of low wages and low benefit levels. Governments find ways to make goods more affordable, as many did in 2020 (partly by ramping up money supply and partly by limiting travel, thereby reducing oil demand and thus oil prices).

As the economy tries to bounce back, inflation and broken supply lines can become problems, as they did in 2021. More fighting tends to take place, as it did with the Ukraine conflict beginning in 2022. In some ways, the economy begins to sound like the book Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell, with a great deal of censorship of opinions not conforming to government-sponsored views.

If the problem really is a resource problem that cannot be fixed with more complexity, the high level of wage disparity will ultimately lead to the population falling because poor people cannot afford necessities. Large cities are particularly prone to collapse. GDP can be expected to fall at the same time.

Politicians cannot admit that such a problem might be lying ahead because they want to be reelected. Educators want students to think that high-paying jobs for people with advanced education will continue to be available in the future. Businesses want people to believe that the cars and homes that they are purchasing will be worthwhile investments for many years in the future. Mainstream media has no choice but to tell the stories governments and businesses want told. Governments offer research grants on projects associated with the favored technologies, giving financial incentives to publish academic papers supporting the chosen narrative.

The whole process is assisted by the fact that academic areas within universities each seem to exist within their own ivory towers. Researchers within economics departments don’t understand that there is a physics reason for the world’s high energy consumption; “scientific modelers” don’t understand the limits of a finite world. Scientific modelers assume that growth can happen indefinitely, while both history and physics indicate that this is impossible.

The chart shown on Slide 19 is a repeat of Figure 1, shown at the beginning of this post. In this chart, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an organization of 37 rich countries of the world, including the US, Canada, most of the countries of Europe, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. Its energy consumption clearly has been squeezed down since 2002, when China’s energy consumption started rising after it joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in December 2001.

As mentioned on Slide 18, the share of world energy consumption of Russia (+ closely affiliated countries) has been squeezed back for a very long time. This may be part of the reason why Russia seems to be so unhappy.

India’s share of world energy consumption is small, but it has been growing.

The share of energy consumption by countries in the Rest of the World has also been growing. This group would include OPEC countries, plus the many poor countries around the world.

In item 4 on Slide 20, regarding vehicles being small, I mean that motorcycles, 3-wheeled auto rickshaws, and mini trucks are used to a much greater extent in India than in the richer countries of the world.

It might be mentioned that China’s per-capita energy consumption is now almost as high as that of Europe. At the time it joined the WTO in 2001, China’s energy consumption per capita was only about 25% of high as that of Europe. China would now seem to be in danger of having its share of world energy consumption squeezed back because it is itself becoming relatively rich.

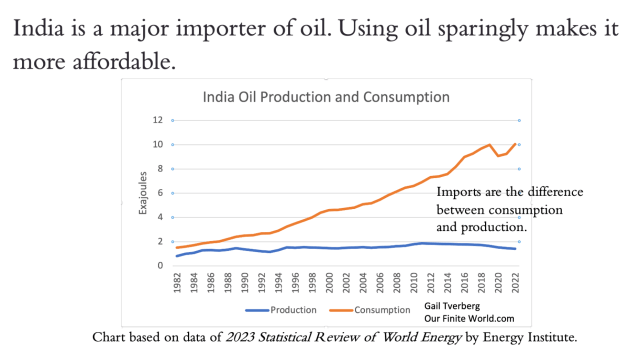

The chart shows that India’s oil consumption has been rising, while its oil production has been trending downward for about a decade. Imports make up the difference. In an oil-constrained world, the question is whether oil imports will really continue to be available at an affordable price. Diesel and jet fuel are in particularly short supply.

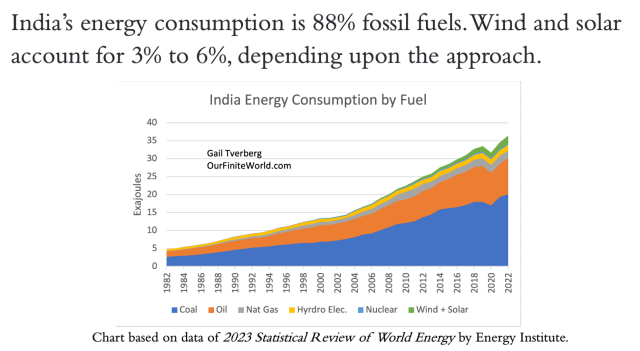

India, like pretty much everywhere else in the world, gets the vast majority of its energy supply from fossil fuels. Using the Energy Institute’s (EI’s) way of counting, about 88% of India’s energy consumption in 2022 came from fossil fuels.

It is confusing to know how to count wind and solar because their electricity is not available when needed. If they are given credit as if they provide dispatchable electricity (which is EI’s approach), then their combined percentage is 6%. If wind and solar are counted as only replacing fuel, then their combined share of energy supply is about 2% or 3% in 2022. The International Energy Agency (IEA) uses the approach providing the lower indications, as do many researchers.

When an economy starts shrinking, as shown in Slide 15, there is a problem with supply lines breaking in an overly complex society. Much of the world experienced some broken supply lines in 2020 and 2021. We can expect more broken supply lines again in future years.

Supply lines are likely to get shorter because of the shortages of diesel and of jet fuel. In particular, fewer goods and services are likely to be shipped across the Atlantic or Pacific Ocean. More trade will be regional in nature. For example, India will probably have a larger share of its total trade with other countries of Southeast Asia than now.

We can expect more fighting among countries because the world will basically be in a situation of “not enough to go around.” India would do well to stay out of these wars.

Intermittency of electrical supply will likely become more of a problem in the future. Replacement parts after storms will be more difficult to obtain.

It is tempting for high energy economies to forget the importance of traditions and religion. Religions help bind groups together. Their laws and traditions give people a way to live with one another, without having a huge army of police being hired to keep order.

As economies become richer, the belief tends to become: The government can save us from all problems. We no longer need our traditional beliefs. All we need to do is focus on more even distribution of goods and services.

Unfortunately, the economy doesn’t work this way. Governments can print money, but they can’t print additional food and water. With broken supply lines, essential commodities such as fertilizer become unavailable. Population must drop for the economies to get back in balance. This is the reason that wars become more frequent, as complexity limits are hit.