The Delicate Balancing Act of Political Reckoning: “The Unpredictable Consequences of Delicate Political Matters

In the realm of politics, there exist certain matters so sensitive, so inherently fragile, that their mere existence can send shockwaves through the social and political fabric of a nation. These issues, oftentimes underpinned by deep-rooted historical, cultural, or ideological tensions, have the potential to disrupt the delicate balance that holds societies together.

—War, Death, Hunger, Pestilence, and Disinformation—

The series of events surrounding Russia’s actions towards Ukraine and the mysterious explosion of the Nord Stream pipeline have sent shockwaves through the global economy. These events have significant implications not only for the countries directly involved, but also for the global economic landscape. In addition, the “mystery” explosion at the Nord Stream pipeline has added to the economic fallout. Nord Stream, a major energy pipeline between Russia and Europe, plays a crucial role in the supply of natural gas to European countries. The explosion has exacerbated the precarious gas supply, caused energy price spikes and disrupted supply chains across the region. The incident was a stark reminder of the deep vulnerability of energy infrastructure resulting from a series of poor geopolitical decisions, and ultimately of the global dependence on stable and secure energy supplies.

The last three years have been a tumultuous period for Ukraine and its impact on the global economy. In the midst of a post-pandemic recovery, the Russian invasion and subsequent aggression have added a new dimension to the challenges facing Europe and the world. The conflict between Russia and Ukraine has caused immense war-related devastation, resulting in loss of life, displacement of communities and damage to infrastructure. The ongoing war is exacerbating the economic burden on Ukraine and has far-reaching implications for neighbouring countries and international stability.

Death: Tragically, the conflict has led to the loss of numerous lives. The human toll, driven by violence and instability, creates an immense humanitarian crisis. The impact of death and destruction on families and communities further deepens the wounds of this ongoing struggle.

Hunger: The prolonged conflict, coupled with the disruption of vital supply chains, has severely affected food security in Ukraine and the world.

Pestilence: Already grappling with the aftermath of a catastrophic pandemic, the world faces additional challenges due to the ongoing conflict.

Disinformation: The spread of inconsistent information has been an alarming aspect of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. This disinformation affects not only the people directly involved but also the perceptions and decision-making of the international community.

The confluence of these five factors—war, death, hunger, pestilence, and disinformation—underscores the immense challenges faced by Ukraine and the broader impact on the international community.

A Secret But Not a Secret: From a Time Until Now…

According to Spiegel International today (read the full article below), the explosion of the Nord Stream pipelines in the Baltic Sea indicates that Kyiv—supposedly—may be responsible. This revelation may alarm the international community and prompt some adjustments in world politics that would ultimately benefit Germany. Investigators have spent the last year tirelessly searching for the truth behind the explosion. The blast was a significant event that unfolded and shook the foundations of Germany’s energy sector with serious implications across Europe’s economy.

An initial disturbance grew into a disaster orchestrated by an elusive command to cripple Germany’s energy supply.

This secret corps demonstrated incredible prowess somewhere in the shadows, skilfully evading detection as they infiltrated the heart of Germany’s energy infrastructure. Their mission was to expose the vulnerabilities embedded in Europe’s energy network. With surgical precision, they executed their plan, leaving a trail of destruction and millions of unsuspecting citizens without access to vital gas supplies.

The impact was staggering. Millions of homes were plunged into darkness as radiators ceased their steady hum and cold penetrated their walls. Vital industries heavily reliant on gas ground to a halt, exacerbating an already struggling economy. As patients shivered in hospitals, the gravity of the situation became painfully clear – the security of Europe’s energy infrastructure had been critically compromised.

The colossal scale of this event could not be underestimated. It was a wake-up call, a stark reminder of our vulnerability in an interconnected world. The once-trusted system that kept the lights on and the wheels turning was now exposed.

As the initial shockwaves reverberated, questions rained down from all corners. How could such a brazen attack have gone unnoticed? Was it an intelligence failure or a profound lapse in security measures? Europe’s energy landscape, once considered robust, was now shaken…

Nations across the continent scrambled to deal with the immediate crisis. Emergency measures were implemented as authorities worked tirelessly to restore broken gas lines and strategise for a future where energy security became imperative. Government agencies undertook an arduous task, compounded by the need to restore confidence in a system that had been shaken to its core.

The incident sent ripples of uncertainty across the continent. It was a moment that challenged Europe’s collective identity, questioning its unity and resilience. It brought the energy debate to the fore, calling for massive investment in renewable technologies, diversified sources and reliable back-up systems.

In the darkest hour, however, clarity emerged. Europe, no stranger to adversity, would be

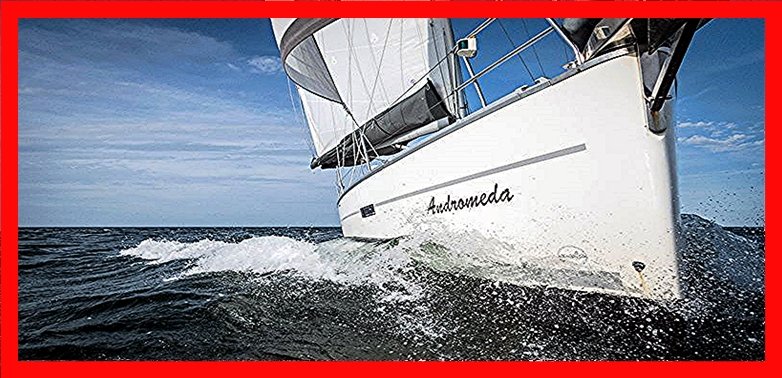

The investigation has led the authorities to some politically sensitive findings. According to the evidence collected thus far, it appears that a commando consisting of divers and explosives specialists chartered a vessel named the Andromeda, which departed from Warnemünde in northern Germany. The ship sailed unnoticed across the Baltic Sea before executing its mission on September 26, 2022, by causing significant damage to three pipes belonging to the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 gas pipelines.

While initially the identities and motives of the culprits were shrouded in mystery, all the evidence now seems to be pointing towards Kyiv. This revelation is sure to have far-reaching consequences and could potentially strain international relations. The implications of an attack on Germany’s energy infrastructure are severe, and accusations are not taken lightly in the political arena.

One thing is certain: the explosion of the Nord Stream pipelines has sent shockwaves throughout the international community and has thrust Kyiv into the spotlight. Whether this is a carefully orchestrated plan or a coincidental twist of events, the implications are vast, and the world will be watching closely as the truth unravels.

Given the circumstances described, it is vital to emphasize that the Nord Stream consortium companies have discreetly engaged with insurance companies to establish their entitlement to compensation that they believe they deserve is almost certain. Nevertheless, we must also prioritize the rights and well-being of individuals globally who have been adversely impacted by the launch of non-traditional inflationary products, the shortages of vital supplies such as food and fuel, resulting in substantial increases in electricity costs that weigh heavily on individuals and economies.

After the attack: damage to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline/ Foto: blueye / Editions by Germán & Co.

Investigating the Nord Stream Attack All the Evidence Points To Kyiv

It’s a spy thriller that has the potential to change the course of international politics: A year ago, a secret commando blew up the Nord Stream pipelines in the Baltic Sea. Since then, investigators have been searching for the perpetrators. The leads they have found are extremely politically sensitive.

SPIEGEL BY LILIANA BOTNARIUC, JÜRGEN DAHLKAMP, JÖRG DIEHL, MATTHIAS GEBAUER, HUBERT GUDE, ROMAN HÖFNER, MARTIN KNOBBE, ROMAN LEHBERGER, FREDERIK OBERMAIER, JAN PUHL, ALEXANDRA ROJKOV, MARCEL ROSENBACH, FIDELIUS SCHMID, SANDRA SPERBER, THORE SCHRÖDER, THOMAS SCHULZ, GERALD TRAUFETTER, WOLF WIEDMANN-SCHMIDT UND JEAN-PIERRE ZIEGLER, AUGUAT 26, 2023

The Andromeda is a decrepit tub. The sides of the vessel are dented and scraped from too many adventuresome docking maneuvers while the porous pipes in the head exude a fecal stench. The 75 horsepower diesel engine rattles like a tractor and the entire boat creaks and groans as it ponderously changes course. The autopilot is broken. Other sailors hardly take any notice at all of the sloop: Just another worn charter vessel like so many others on the Baltic Sea.

The perfect yacht if you’re looking to avoid attracting attention.

According to the findings of the investigation thus far, a commando of divers and explosives specialists chartered the Andromeda almost exactly one year ago and sailed unnoticed from Warnemünde in northern Germany across the Baltic Sea before, on September 26, 2022, blowing holes in three pipes belonging to the natural gas pipelines Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2. It was a catastrophic assault on energy supplies, a singular act of sabotage – an attack on Germany.

The operation was aimed at “inflicting lasting damage to the functionality of the state and its facilities. In this sense, this is an attack on the internal security of the state.” That’s the legal language used by the examining magistrates at the German Federal Court of Justice in the investigation into unknown perpetrators that has been underway since then.

Unknown because – even though countless criminal investigators, intelligence agents and prosecutors from a dozen countries have been searching for those behind the act – it has not yet been determined who did it. Or why. The findings of the investigation thus far, much of them coming from German officials, are strictly confidential. Nothing is to reach the public. On orders from the Chancellery.

“This is the most important investigation of Germany’s postwar history because of its potential political implications,” says a senior security official. Those within the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA) who are responsible for the Nord Stream case, members of Department ST 24, are even prohibited from discussing it with colleagues who aren’t part of the probe. Investigators are required to document when and with whom they spoke about which aspect of the case – a requirement that is extremely unusual even at the BKA, Germany’s equivalent to the FBI.

There is a lot at stake, that much is clear. If it was a Russian commando, would it be considered an act of war? According to Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, an attack on the critical infrastructure of a NATO member state can trigger the mutual defense clause. If it was Ukraine, would that put an end to Germany’s ongoing support for the country with tank deliveries or potentially even fighter jets? And what about the Americans? If Washington provided assistance for the attack, might that spell the end of the 75-year trans-Atlantic partnership?

“It immediately raised the question for me: How can we better protect ourselves.”

GERMAN INTERIOR MINISTER NANCY FAESER

Beyond that, as if more critical questions were needed, the Nord Stream attack has provided a striking blueprint for just how easy it can be to destroy vital infrastructure like pipelines. “It immediately raised the question for me: How can we better protect ourselves,” says German Interior Minister Nancy Faeser. “The disruption of critical infrastructure can have an enormous effect on people’s lives.”

There are plenty of targets for such attacks: internet nodes, oil pipelines, nuclear power plants. One can assume that close attention is being paid in North Korea, Iran and other terrorist states on what exactly will happen now. If the perpetrators are not found, if the sponsors of the attack are not sanctioned, if there is no military reaction – then the deterrents standing in the way of similar attacks in the future will be significantly fewer.

But there are leads. DER SPIEGEL, together with German public broadcaster ZDF, assembled a team of more than two dozen journalists to track them down over a period of six months. Their reporting took them around the globe: from the Republic of Moldova to the United States; from Stockholm via Kyiv and Prague to Romania and France. Much of the information comes from sources who cannot be named. It comes from intelligence agencies, investigators, high ranking officials and politicians. And it comes from people who, in one way or another, are directly linked to suspects.

At some point in the reporting, it became clear that the Andromeda had played a critical role, which is why DER SPIEGEL and ZDF chartered the boat once the criminal technicians from the BKA had released it. Together, six reporters followed the paths of the saboteurs across the Baltic Sea to the site of one of the explosions in international waters.

This voyage on its own did not reveal the secrets of the attack, but it made it easier to understand what may have happened and how – what is plausible and what is not. And why investigators have become so convinced that the leads now point in just one single direction. Towards Ukraine.

That consensus in itself is striking, say others – particularly politicians who believe the attack from the Andromeda may have been a “false flag” operation – an attack intentionally made to look as though it was perpetrated by someone else. All the leads point all-too-obviously towards Kyiv, they say, the clues and evidence seem too perfect to be true. The Americans, the Poles and, especially, the Russians, they say, all had much stronger motives to destroy the pipeline than the Ukrainians.

Still others believe that too many inconsistencies remain. Why did the perpetrators use a chartered sailboat for the operation instead of a military vessel? Why wasn’t the Andromeda simply scuttled afterwards? How were two or three divers on their own able to blow up pipelines located at a depth of around 80 meters (260 feet) beneath the waves?

The story of the operation is a preposterous thriller packed full of agents and secret service missions, special operations and commando troops, bad guys and conspiracy theorists. A story in which a dilapidated sailboat on the Baltic Sea plays a central role.

The Search

It’s a chilly January day in Dranske, a town on the northwest tip of the German Baltic Sea island of Rügen. The law enforcement officials show up at 9:45 a.m. for the search, 13 of them from the BKA and Germany’s Federal Police, including IT forensic experts, a crime scene investigator and explosives specialists. Their target on this morning are the offices of Mola Yachting GmbH, and they tell the shocked employees that they have a search warrant for a boat that was chartered from the premises. The punishable offense listed on the warrant: “The effectuation of an explosive detonation, anti-constitutional sabotage.”

They demand to know where the Andromeda is. The technical chief of Mola tells them it is in winter storage, a few hundred meters away. He leads the group of law enforcement officials along a secluded private road to a former East German army facility, as a confidential memo documents. The Andromeda is sitting on blocks out in the open, with workers sanding down the hull. The search begins at 11:05 a.m. It lasts three days.

The investigators are lucky. Mola didn’t clean the boat before storing it for the winter, and the saboteurs were the last people to charter the vessel. A plastic bottle “with apparently Polish labeling” is found next to the sink. Beneath the map table is a single “barefoot shoe.” According to the BKA’s search log, file number ST 24-240024/22, the officials remove the marine navigation system, a model called Garmin GPSMAP 721.

The sailing yacht Andromeda in the Baltic Sea / Foto: Christian Irrgang / DER SPIEGEL

The next day, the federal police bring two bomb-sniffing dogs onboard; they have to be hoisted up using a kind of winch. They spend more than an hour sniffing around onboard the Andromeda. With success, as forensics experts would later confirm in the lab. On a table belowdecks and even on the toilet, they are able to find substantial traces of octogen, an explosive that also works underwater.

Ever since the search of the ship on those days in January, German investigators have been certain that the Andromeda is the key to the Nord Stream case. Finally, a breakthrough.

Early in the investigation, it seemed that such a breakthrough would never come. The few leads the detectives had all turned up nothing of substance, and they had no clear indications of who the perpetrators might be. But then, a few weeks after the attack, intelligence was passed to the BKA indicating that a sailboat was involved.

To avoid causing concern and attracting unwanted attention, the investigators contacted boat rental companies in Rostock and surroundings one at a time – ultimately zeroing in on Mola and the Andromeda.

It was a rather surprising development for the public at large, particularly given that other scenarios seemed so much more likely: submersibles, specialized ships, at least a motorboat or two. But a single sailboat as the base of operations for the most significant act of sabotage in European history?

German officials were also skeptical at first. The federal public prosecutor general commissioned an expert analysis with a clear question of inquiry: “Whether such an act could be carried out with a completely normal yacht or if a much, much larger vessel was necessary.” Such was the formulation used by Lars Otte, the deputy head of the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, during a confidential, mid-June session of the Internal Affairs Committee of German parliament, the Bundestag. Speaking to the gathered parliamentarians, he stressed: “The assessment of the expert is: Yes, it is also possible with a completely normal yacht of the kind under consideration.”

The Andromeda

On September 6, 2022, the Andromeda was bobbing in the waves along with dozens of other boats in a marina in Rostock’s Warnemünde district waiting to be taken out by its next renters. For the last decade, it has been plowing through the Baltic Sea every few days, with a new charter crew at the helm. The Andromeda is a Bavaria 50 Cruiser, built in Bavaria in 2012 and frequently belittled by sailors as the “Škoda of the seas.” Not exactly elegant, but practical, a bit like a floating station wagon: 15.57 meters (roughly 51 feet) long and a beam of 4.61 meters, it is rather affordable for its size.

Belowdecks, it has five small cabins with space for a maximum of 12 people, if you don’t mind a bit of crowding. The double berths are hardly 1.2 meters wide. By contrast, though, there is plenty of storage space and the kitchenette is relatively spacious, complete with a gas stove and a banquette surrounding a varnished dining table. A swimming platform can be folded down from the stern, making it easy to take a dip. It is ideal for divers with their heavy equipment.

The marina Hohe Düne is located around 10 kilometers from the Rostock city center as the crow flies, a strangely lifeless place with a giant wellness hotel and a solitary pizzeria. Long piers wind their way out into the water to 920 morages, with a small wooden structure right in the middle of Pier G. Those who have chartered a yacht with Mola Yachting must register here, complete with identification, sport boat license and a 1,500-euro deposit.

On September 6, according to reporting by DER SPIEGEL and ZDF, a sailing crew checked in at the Mola shack in the early afternoon to take out the Andromeda. The charter fee had apparently been paid by a Warsaw travel agency called Feeria Lwowa, a company with no website or telephone number.

According to the Polish commercial registry, the company is headed by a 54-year-old woman named Nataliia A., who lives in Kyiv. She completed a course of study in early childhood education, but has no recognizable experience in the tourism industry. She has a Ukrainian mobile phone number. If you call it, a woman answers – before immediately hanging up once you identify yourself as a journalist. A few days later, a Ukrainian “police officer” called back, threatening the reporter with charges of “stalking,” citing a rather flimsy justification. Feeria Lwowa’s address in Warsaw likewise leads nowhere. There is no office and there are no local employees. It looks as though it is a shell company.

Who Is Ştefan Marcu?

And something else would soon prove to be extremely challenging for investigators: When the saboteurs showed up at the Mola shack to check in for their rental of the Andromeda, they apparently presented a Romanian passport. It had been issued to a certain Ştefan Marcu, as official documents indicate. But who was he? Did he have anything to do with the attack?

Marcu opens the steel gate to his property wearing shorts and flipflops. It is the middle of July, a hot day in Goianul Nou, a village in Moldova just north of the capital of Chiᶊinǎu. The Ukrainian border isn’t even 50 kilometers from here.

Ştefan Marcu is a sturdily built man with a deep tan and a black moustache, an engineer with his own company. A team from DER SPIEGEL and ZDF along with reporters from the investigative networks Rise Moldova and OCCRP managed to track him down. The two-story home where he lives with his family is the most attractive one on their street. Marcu stares down at the note the reporters show him, bearing the number 055227683.

He recognizes it immediately. He says he is a citizen of Moldova, but that the number belonged to his old Romanian passport, which expired the previous October. The last time he used the passport, he says, was in 2019 for a vacation in Romania and then, a couple months after that, for a trip to Bulgaria. He says he has no idea how his name got mixed up in the pipeline story. It’s the first time he’s heard about it, he insists. Aside from the reporters, nobody else has asked him about it, he says, no police officers and no intelligence agents.

After he received his new passport, he says, the woman at the office invalidated his old one. “When I got home, I burned it. I threw it in the oven,” Marcu says.

But the data from his passport, officials believe, seems to have been used to produce another document, a falsified passport that was then used to charter the Andromeda. Complete with a new photo. The photo, though, is not of Ştefan Marcu, the 60-year-old from Moldova, but of a young man in his mid-20s with a penetrating gaze and military haircut. The man in the photo is very likely Valeri K. from the Ukrainian city of Dnipro. He apparently serves in the 93rd Mechanized Brigade of the Ukrainian army.

A Stop in Northern Rügen

It’s not possible to determine precisely when the saboteurs left the Hohe Düne marina. But the very next day, on September 7, they made their first stop just 60 nautical miles away in Wiek, a tiny harbor on the north coast of Rügen. Under normal circumstances, it is part of a long but idyllic sailing trip along the coast of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, past the Fischland-Darss peninsula and the island of Hiddensee.

It takes the team of reporters around 12 hours to sail this first leg of the journey, in pleasant, mid-July weather and calm seas. For most of that distance, the Andromeda is propelled by its motor, at a relatively constant clip of seven to eight knots. In a strong wind, when the mainsail can be set on the 22-meter-tall mast along with the jib, the ship can reach speeds of 10 to 11 knots.

In contrast to Warnemünde, Wiek is a solitary, isolated place, vastly different from the busy Rostock marina. Those wishing to load up their boat in Rostock have to push a handcart back and forth across long piers past dozens of other boats and crews. In Wiek, though, it is possible to drive a delivery truck right up to one of the few moorages that are large enough for a vessel the size of Andromeda. When the skipper of the DER SPIEGEL/ZDF voyage called ahead to reserve a moorage, the harbormaster asked: “Do you want the same spot as the terrorists?”

Still, during our visit, marina staffers prove reluctant to talk about the Andromeda and its stopover, at least not on the record. One of the workers who has clear memories of the sailboat’s layover and who dealt directly with the crew says that the people on board seemed physically fit and familiar with each other, and that they spoke in a language he was unfamiliar with.

The crew was made up of five men and a woman, says the harbormaster, who filled up the fuel tank of the Andromeda for the saboteurs. That was during the boat’s second stop in Wiek, on the return trip to Warnemünde. He wrote down the amount paid for the diesel in a black notebook, the same one he uses to record the fuel purchased by the crew of reporters.

The harbormaster flips back through his notebook and finds two entries that may have been for the diesel purchased by the team of saboteurs: one for 665.03 euros and one for 1,309.43 euros on September 22 and 23, respectively. In addition to filling the boat’s tank, though, he recalls, he was also asked to fill up several canisters. One of the men paid for the fuel in cash, pulling a striking number of large-denomination euro bills out of his pocket to do so – but he didn’t leave a tip.

On the Pea Islands

After the first stopover in Wiek, the Andromeda disappeared for an extended period. With the help of a meter, investigators have determined that the crew didn’t sail the ship and used the motor instead. Around 10 days later, the vessel apparently reappeared off the island of Christiansø, not much more than a rock jutting out of the waves near Bornholm, so small that it is sometimes called Pea Island. The port lies attractively below defensive fortifications built in 1684. The island, located near the easternmost point of Denmark, is home to hardly more than 100 residents, but it is a popular destination for day-trippers who sail over from the vacation island of Bornholm for a lunch of kryddersild.

It seems safe to say, though, that the saboteurs weren’t there for the pickled herring: Christiansø is the nearest port to the site of the detonations. And a chartered sailboat doesn’t stand out at all, with almost 50 vessels sailing in and out on busy days, says Søren Andersen. The chief of administration for the tiny islands, Anderson is sitting among portraits of the Danish royal family in a white-plastered building with a green door made of wood and a sign reading “Politi,” police. “In December, the Danish police requested us to share all the port data” from September 16 to 18, 2022, says Anderson.

An Inspection in Poland

That was when the commando on board the Andromeda made a brief detour – directly south to Poland. On September 19, exactly one week before the pipelines were blown up, the Andromeda docked in Kołobrzeg, Poland, a Baltic Sea resort known for its saline springs and usually packed with tourists during the summer months. And with sailboats. The Andromeda only stayed for 12 hours.

Poland was always one of the most adamant opponents of Nord Stream 2 and vociferously demanded over the course of several years that the project be stopped. Warsaw long viewed Germany’s dependence on energy from Moscow as an existential threat. It would be fair to say that Poland had a strong interest in eliminating this threat to its security right off its coastline once and for all.

In May, German investigators traveled to Poland for a “meeting at the level of the prosecutor’s offices conducting the investigation,” as it would later be described. One question addressed during that meeting was whether the saboteurs had received any support while in Kołobrzeg, either of a material nature, or in the form of personnel. They wanted to know if the port may have been used as a logistical hub.

The responsible public prosecutor in Danzig, from the department for organized crime and corruption, vehemently denies such a scenario when asked. “There is absolutely no evidence for the involvement of a Polish citizen in the detonation of the Nord Stream pipelines,” he says. “The investigation has found that during the stay in a Polish harbor, no objects were loaded onto the yacht.” In fact, he notes, “the crew of the yacht was checked by Polish border control officials” because they had raised suspicions. Perhaps because of the falsified documents used by the crew? Whatever triggered their concerns, the border control officials made a note of the personal information they had presented.

Image by Germán & Co.

The Pipelines

By September 20, the Andromeda had already departed from Kołobrzeg. By this time, the explosives had likely already been laid and equipped with timed detonators. Christiansø, the sailboat’s previous port of call, is, in any case, the closest to the main detonation site. It is located just 44 kilometers – less than a three-hour voyage to the northeast – from the coordinates 55° 32′ 27″ north, 15° 46′ 28.2″ east.

The Baltic Sea gets rather lonely to the east of the Pea Islands. There are fewer ferries, fewer tankers and not too many sailboats either. For miles around, there is nothing but water and sky.

There is, however, something to see on the sonar, some 80 meters below: Four pipes, each with an inside diameter of 1.15 meters, wrapped in up to 11 centimeters of concrete which keeps them on the sea floor, and a layer to protect against corrosion. Beneath that is four centimeters of steel and a coating to ensure the natural gas flows more freely on its long journey from Russia to Germany.

Nordstream 1 begins in the Russian town of Vyborg and runs through the Gulf of Finland and crosses beneath the Baltic Sea before reaching the German town of Lubmin, located near the university town of Greifswald.

The double pipeline is 1,224 kilometers long and consists of 200,000 individual segments, most of which were produced by Europipe in Mühlheim, Germany. During construction, 15 freight trains per week rolled into the ferry port of Sassnitz, where the pipe segments were loaded onto a ship. The project’s price tag was 7.4 billion euros, with most of it paid for, directly or indirectly, by the Russian state.

It went into operation in 2012, sending almost 60 billion cubic meters of natural gas from the Russian fields Yuzhno-Russkoye and Shtokman, located on the Barents Sea, to Germany. In 2018, the pipeline accounted for 16 percent of all European Union natural gas imports. Nord Stream 1 was one of the most important pipelines in the world.

In spring 2018, dredgers again sailed into the Bay of Greifswald to make way for Nord Stream 2, also a double pipeline. This one starts a bit further to the south, in the town of Ust-Luga, located in the Leningrad Oblast – but most of it runs parallel to the first pipeline. It was planned to carry 55 billion cubic meters of Russian natural gas per year to Germany. Taken together, the two pipelines were able to transport far more than Germany consumed each year. Most Germans were in favor of the new pipeline project, blinded to their country’s growing dependency on Moscow by the cheap price of Russian gas. A 2021 survey among supporters of all political parties found that an average of 75 percent of Germans were in favor of Nord Stream 2.

Security policy experts and many of Germany’s international allies, by contrast, were aghast. Nord Stream 1 had already tied Germany far too closely to Russia, they felt. And now Berlin wanted to import even more energy from Vladimir Putin’s empire? The Americans, in particular, were vocal about their opposition to the project. Indeed, Washington thought Nord Stream 2 was so dangerous that it warned Germany that its completion would significantly harm U.S.-German relations.

Ukraine was also radically opposed to the new pipeline. Significant quantities of Russian natural gas flowed to Western Europe through overland pipelines across Ukrainian territory. A second pipeline beneath the Baltic would make parts of the Ukrainian pipeline network obsolete. Kyiv saw Nord Stream as a direct threat to the country.

In September 2021, Nord Stream 2 was completed, but it did not go into operation. And a few months later, the Russian invasion of Ukraine put an end to the political debate – and left Germany scrambling to free itself from dependency on energy imports from Russia as quickly as possible. The initial plan called for continuing to import natural gas through Nord Stream 1 for a time, but the second pipeline was essentially dead in the water.

For the time being, at least. But politics can be fickle, consumers and industry have a fondness for cheap energy and Putin wouldn’t be around forever, would he? The four pipes lay on the seabed, ready to be put back in use once that time came.

Explosions in the Baltic Sea

At 2:03 a.m. on September 26, a blast wave rippled through the bed of the Baltic Sea, powerful enough to be recorded by Swedish seismographs hundreds of kilometers away. The welded seam between two segments of pipe A of Nord Stream 2 was shredded. It was a precise cleavage, likely caused by a relatively small amount of perfectly placed specialized explosive material: octogen. Exactly the same explosive of which forensics experts would later find traces onboard the Andromeda. The explosion initially ripped a roughly 1.5-meter gap in the pipe, but the gas gushing out enlarged the leak.

Seventeen hours later, at 7:04 p.m., there was another blast wave, this time 75 kilometers to the north. It was much stronger, and there were several explosions. Above water, the muffled blast could be heard several kilometers away. This time, both pipes belonging to Nord Stream 1 were destroyed: a 200-meter section of pipe A and a 290-meter segment of pipe B. A 3-D visualization based on underwater camera footage and sonar readings shows deep craters, piles of rubble and bits of pipeline sticking up diagonally from the seafloor.

Initially, nobody knew just how dramatic the situation was, not even the operators of the two pipelines, Nord Stream AG and Nord Stream 2 AG. Both companies are majority owned by the Russian natural gas giant Gazprom. Initially, they only registered a drastic fall in pipeline pressure, but technicians were immediately concerned that something might by wrong, as were military representatives in the region. On the morning of September 27, a Danish F-16 fighter discovered strange bubbles on the surface of the water, and the Danish military published the first images that afternoon: Natural gas rising up from the bottom of the Baltic had formed circles of bubbles up to 1,000 meters across on the water’s surface not far from Bornholm.

It’s not yet possible to say with complete certainty how the perpetrators went about their business. But the findings of the international investigation make it possible to reconstruct much of what took place. Data from geological monitoring stations, videos and sonar data from the seafloor provide additional clues. That data comes from a Swedish camera team and from Greenpeace, both of which launched their own surveys using underwater devices. For experts, the publicly available information paint a largely consistent picture, according to which the group of saboteurs was likely made up of six people – five men and a woman. Likely a captain, divers, dive assistants and perhaps a doctor.

According to former military and professional divers, the operation would have been possible, though challenging, with such a team. “It’s pitch black down there, cold, and there are currents,” says Tom Kürten. As a technical diver and expedition leader, he has been inspecting wrecks on the bottom of the Baltic Sea for many years. With the correct equipment, it is possible to dive to depths of 100 meters or more, and he believes it would be impossible to locate the pipelines without technical assistance. Indeed, with a small DownScan, a sonar device, it would be relatively simple, he says. And once the spot has been identified, all you have to do, he says, is throw a “shot line” overboard, a rope with a weight on the end that guides the divers into the depths.

For challenging dives, Kürten also uses a rebreather, which recycles exhaled air and replenishes it with oxygen for the next breath. The advantage is that no tanks are needed, and such devices also produce fewer bubbles, which can be helpful if you are seeking to avoid unwanted attention. Still, such an operation takes time. For 20 minutes spent working at a depth of 80 meters, a total of three hours of dive time is necessary, Kürten estimates. During the ascent, decompression stops are vital so that the body can adjust from the high pressure on the seafloor to the lower pressure at the surface. It’s a rather complex undertaking, but certainly possible during a long trip.

The pipe tore open along a length of approximately 100 meters. A so-called “cutter charge” was likely used, directly over a welded joint.

Later, when German investigators undertook a closer examination of the detonation sites, specialists from the maritime division of the German special forces unit GSG 9 dived down to take a look.

However you look at it, the operation could not have been performed by amateur divers – nor by hobby sailors. When the team of reporters in the Andromeda arrived at the site above where the explosions took place, a force 5 or 6 wind was blowing, it was raining, and the swells were significant. Standard Baltic Sea weather, in other words – in which it is difficult to keep a sailboat in one spot. According to weather data, mid-September 2022 was similar for several days, though it was calmer both before and afterward.

Explosives expert Fritz Pfeiffer produced an expert opinion for Greenpeace regarding the potential destructive power of the detonations, since the environmental group was interested in knowing how much damage had really been done to the pipeline and what that might mean for the environment.

An Operation Straight Out of Hollywood

On underwater images of Nord Stream 1, Pfeiffer identified craters that he believes were created by large amounts of explosives detonating next to the pipeline. Investigators, though, think that a total of less than 100 kilograms of explosives were used and that the sudden release of the highly pressurized natural gas caused much of the damage.

Not far from the long stretches of destroyed pipes belonging to Nord Stream 1, the A pipe of Nord Stream 2 was attacked a second time – the same line that had already been severed 17 hours earlier further to the south. The pipe tore open along a length of approximately 100 meters. A so-called “cutter charge” was likely used, directly over a welded joint. Pfeiffer believes that just eight to 12 kilograms of octogen would have been necessary for such a detonation.

The B pipe of Nord Stream 2, meanwhile, wasn’t harmed at all – and could easily be put into use even today. But why did the perpetrators leave one of the four pipes undamaged? There are some indications that the saboteurs confused the A and B pipes of Nord Stream 2 in the darkness and unintentionally attacked the same pipe twice.

Whatever the case, experts seem to agree on one salient fact: specialized submarines or remote-controlled submersibles were not necessary for the operation. But there are several questions to which no answer has yet been found. How were the bombs detonated? Why did so much time pass between the first explosion and the three that followed? Some experts believe that they might have had difficulties in activating the explosives – either via a delayed detonator or a remote detonator.

The Warnings

Perhaps the attack could have been prevented in the first place. It didn’t come as a complete surprise, after all. It had been announced several months beforehand, in detail. But the warning wasn’t taken seriously enough in the right places.

An encrypted, strictly confidential dispatch from an allied intelligence agency was received by the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND – Germany’s foreign intelligence agency) in June 2022. Such dispatches are hardly an anomaly, but this one contained a clear warning. It was from the Netherlands’ military intelligence agency, which goes by the initials MIVD and is well known for its expertise in Russian cyberwarfare techniques. On this occasion, though, the agency’s alarming information seemed to have come from a human asset in Kyiv.

The Dutch also informed the CIA – which, just to be on the safe side, also forwarded it onward to the Germans.

The confidential dispatch sketched out an attack on the Nord Stream pipelines. The plan called for six commando soldiers from the Ukraine, concealed with fake identities, to charter a boat, dive down to the bottom of the Baltic Sea with specialized equipment and blow up the pipes. According to the information, the men were under the command of Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi, but President Volodymyr Zelenskyy had apparently not been informed of the plan. The attack was apparently planned to take place during the NATO exercise Baltops on the Baltic Sea. The content of the secret dispatch was originally reported on by the Washington Post in early June.

The BND forwarded the warning to the Chancellery, but at German government headquarters, it was deemed irrelevant. After all, it only arrived at the Chancellery after the NATO maneuver had come to an end, and nothing had happened. That is why nobody sounded the alarm, says one of the few people who learned of the warning when it arrived. Most German security officials believed the information contained in the dispatch was inaccurate.

As a result, no protective measures were introduced, no further investigations were undertaken and no preparations were made to potentially prevent an attack at a later point in time. The Federal Police, the German Navy and the antiterrorism centers never even learned of the warning.

Nor did the German agency responsible for the oversight of Nord Stream.

In the early morning hours of September 26, Klaus Müller, president of the Federal Network Agency, received a telephone call. His agency is responsible for regulating Germany’s electricity and natural gas grids. Christoph von dem Bussche, head of the company Cascade, which operates 3,200 kilometers of Germany’s natural gas pipelines, was on the other end of the line. According to sources in Berlin, Bussche told Müller that one of the Nord Stream pipelines had just experienced an inexplicable loss of pressure.

Washington carefully approached Kyiv with a clear message: Don’t do it! Abort the operation!

The head of the Federal Network Agency must have immediately realized how important that phone call was. He called German Economy Minister Robert Habeck.

Habeck, who is also the vice chancellor, was the first cabinet member to learn of the attack on the pipelines. Sources indicate that he was just as surprised as Müller had been. Neither of them had apparently known about the warning that had been received three months before.

It had also apparently not been discussed in the German Security Cabinet, the smaller group of ministers that has been meeting regularly in the Chancellery since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Müller, though, is the first person who should have been informed of increased risks posed to the pipeline: He is in charge of ensuring the smooth operation of Germany’s numerous pipelines, and of protecting them if need be.

The U.S., by contrast, apparently sprang into action in summer 2022, even if the Americans didn’t initially trust the Netherlands’ source. Washington carefully approached Kyiv with a clear message: Don’t do it! Abort the operation! The German weekly newspaper Die Zeit and public broadcaster ARD were the first to report on Washington’s warning to Kyiv. But the message from the American’s apparently wasn’t taken seriously. Perhaps Washington lacked a certain amount of credibility, particularly given how clear they had made it in the past that they were deeply opposed to the gas pipelines connecting Germany and Russia.

Was there perhaps even more information that wasn’t passed along? Did the well-informed Dutch military intelligence agents know even more than they shared, such as who was to be on board the ship and perhaps even from which Ukrainian unit they came from? If so, that information is no longer available. Leaving the German investigators to assemble the puzzle pieces on their own.

Searching For Clues In Ukraine

One lead stems from the falsified passport of Ştefan Marcu. And from the man whose photo is apparently on that document: Valeri K.

Back in June, Lars Otte, the federal prosecutor, told members of the Internal Affairs Committee at the Bundestag that investigators had been able to “almost certainly identify a person who may have taken part in the operation.”

The lead takes us to a large city in central Ukraine, to an abominable Soviet-era prefab residential building on the outskirts of Dnipro. The structure has eight, not entirely rosy-smelling entrances, a bar and a minimarket called Stella on the ground floor.

On the third floor of the first entrance is an apartment that is registered to the father of Valeri K. He, too, is called Valeri – and both are members of the military, say neighbors.

Nobody opens the door, despite extended knocking. Instead, the neighbors peek out, an elderly married couple. They say that the Valeris actually live in the building next door and that they only rent out this apartment. The younger Valeri K.’s grandmother, the couple says, used to work at Stella, and suggested dropping by there.

It’s stuffy inside the store, and smells of dried fish. The saleswoman says that the grandmother is now the janitor of the neighboring building. Five minutes later, Lyubov K. sets aside her broom and sits down on a bench. She’s a small woman with red-dyed hair and speaks Russian. She says she doesn’t want to speak with the press, but remains seated on the bench. When asked if her grandson Valeri is in the army, she says “yes.” What does he do there? “I don’t know.” She does say, though, that her son and grandson had only been called up a few months before. The conversation remains brief, ending with the grandmother claiming that her grandson couldn’t have been onboard the Andromeda because he doesn’t have a passport and is unable to travel overseas.

Another neighbor, a retiree with gray curls and wearing a blue shirt, is more talkative. Her son, she says, went to school with Valeri senior and they also worked together. The two of them had taken a job at a shipyard in Turkey several years before.

Then, the neighbor says, Valeri senior embarked on a completely different career path, smuggling migrants across the Mediterranean on a sailboat. But the operation was busted and the Ukrainians involved arrested. The neighbor says that the younger Valeri K. wasn’t involved though.

The neighbors don’t have much to say about him. His presence on social media is also limited, apparently limited to VK, a Facebook clone that is popular in Ukraine and Russia.

The most striking thing about the younger Valeri K. is that he is a follower of the openly nationalist youth organization VGO Sokil. It offers young men training in shooting and diving.

His most recent active VK profile is under the name “Chechen from Dnipro,” and it is linked to a telephone number. If you enter the number into an App like Getcontact, you can see the names under which the number is saved in other people’s contact lists. Among the names for Valeri’s number is: “K. 93rd Brigade.”

There are also leads to his long-time girlfriend Inna H. The two apparently aren’t together any longer, but they have a son together. The mother and child no longer live in Dnipro, but in the German city Frankfurt an der Oder.

They live in a gray housing block just a few hundred meters from the Polish border. There are a number of Ukrainian refugees living in the building, including several relatives of Valeri K.: Inna H., the ex-girlfriend who is the mother of his son, his younger sister Anya K. and apparently also his maternal grandmother Tetyana H.

In May, they received a visit from the police, who searched the apartment. A DNA sample from Valeri K.’s son was then compared with traces found on the Andromeda. But there was no match.

Inna H. lives on one of the upper floors of the apartment block, but the door is opened by an elderly lady when a team of reporters from DER SPIEGEL rings the doorbell. She doesn’t give her name, but she looks like the grandmother, Tetjana H., in photos. She doesn’t want to talk to journalists.

If people have something to say, she says, they should discuss it with the authorities.

Asked about the accusations against Valeri K., she says only: “We are a simple family, the Germans saved us. Why would we want to do them any harm?”

Little Doubt

Officially, politicians and the Office of the Federal Prosecutor are still holding back with any conclusions. Currently, it is not possible to say “this was state-controlled by Ukraine,” Federal Prosecutor Otte says. “As far as that is concerned, the investigation is ongoing, much of it still undercover.”

Behind the scenes, though, you get clearer statements. Investigators from the BKA, the Federal Police and the Office of the Federal Prosecutor have few remaining doubts that a Ukrainian commando was responsible for blowing up the pipelines. A striking number of clues point to Ukraine, they say. They start with Valeri K., IP addresses of mails and phone calls, location data and numerous other, even clearer clues that have been kept secret so far. One top official says that far more is known than has been stated publicly. According to DER SPIEGEL’s sources, investigators are certain that the saboteurs were in Ukraine before and after the attack. Indeed, the overall picture formed by the puzzles pieces of technical information has grown quite clear.

And the possible motives also seem clear to international security circles: The aim, they says, was to deprive Moscow of an important source of revenue for financing the war against Ukraine. And at the same time to deprive Putin once and for all of his most important instrument of blackmail against the German government.

But crucial questions remain unanswered. From how high up was the attack ordered and who knew about it? Was it an intelligence operation that the political leadership in Kyiv learned about only later? Or was it the product of a commando unit acting on its own? Or was it a military operation in which the Ukrainian General Staff was involved? Intelligence experts and security policy experts, however, consider it unlikely that Ukrainian President Zelenskyy was in on it: In cases of sabotage, the political leadership is often deliberately kept in the dark so that they can plausibly deny any knowledge later on. In early June, when the first indications of Kyiv’s possible involvement came to light, Zelenskyy strongly denied it. “I am president and I give orders accordingly,” he said. “Nothing of the sort has been done by Ukraine. I would never act in such a manner.”

In any case, it is difficult terrain for the BKA, not only politically, but also in practical terms. The German criminal investigators cannot conduct investigations in Ukraine, and it isn’t expected that Kyiv will provide much support. The German authorities have also shied away from submitting a request to Ukraine for legal assistance because doing so would require that they reveal what they know. That could provide Ukraine the opportunity to cover up any traces that may exist and to protect the people responsible. Asked whether there will be arrest warrants one day, an official familiar with the events replies: “We need a lot of patience.”

“Everyone is shying away from the question of consequences.”

SENIOR GERMAN GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL

A Ukrainian commando carried out an attack on Germany’s critical infrastructure? Officials at the Chancellery in Berlin have been discussing intensively for months how to deal with the sensitive findings of the investigation. Chancellor Olaf Scholz has also been debating possible consequences with his closest advisers. Of course, there aren’t many options available to them. A change of course in foreign policy or the idea of confronting Kyiv with the findings seems unthinkable.

The situation changed in March, when the New York Times, Germany’s Die Zeit and Berlin-based public broadcaster RBB first reported on the evidence pointing to Ukraine. A little bit later, the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper also published its own investigative report. Soon after, Jens Plötner, an adviser to the chancellor, openly addressed the articles in a phone call with Andriy Yermak, one of President Vlodymyr Zelenskyy’s closest confidants. The answer was clear: Yermak apparently assured the Germans that the Ukrainian government had not been involved in the plot and that no one from the security apparatus knew who was behind it.

Few in Berlin want to think right now about what action should be taken if the involvement of Ukrainian state agencies is proven. On the one hand, Germany couldn’t simply brush off such a serious crime. But suspending support for Ukraine in its war against Russia also wouldn’t be an option. “Everyone is shying away from the question of consequences,” says one member of parliament with a party that is a member of the German government coalition.

The fact that politicians who normally might at least speak off the record are remaining silent and simply ignoring inquiries is an indicator of just how delicate the situation is. Inquiries about the situation regarding the attack on the Nord Stream pipeline – in ministries, at party headquarters and in parliamentary offices – as to how it is being discussed within the parties or whether the government is already thinking through scenarios for the eventuality that the Ukrainian leadership knew about the operation, go nowhere.

“No,” says Irene Mihalic, the first parliamentary secretary of the Green Party, there was almost no discussion about the issue before the summer legislative recess. She says her party will wait for the outcome of the investigations, and that anything else would be pure speculation.

In fact, the information available to members of parliament in this case is also extremely thin. On the one hand, the federal public prosecutor naturally provides only scant information about ongoing investigations. More importantly, the federal government is keeping all the findings under wraps. Even most members of Scholz’s cabinet as well as the deputies in the Parliamentary Control Committee, which is tasked with oversight of the work of the intelligence services, don’t know much more than what is publicly reported about the attack.

The gatekeeper for information flows sits on the seventh floor of the Chancellery, diagonally opposite Olaf Scholz. Wolfgang Schmidt, the chancellor’s closest confidant and head of the Chancellery, maintains intensive contact with the investigators. He is also briefed each week by the intelligence services and is happy to pick up the phone to make inquiries of his own. When asked, Schmidt says he doesn’t want to comment on the Nord Stream case.

Sources within the investigation say they have been amazed by the level of interest the Chancellery head has shown in the progress of the proceedings. And at the same time, how little Berlin seems to care about shedding light on this unprecedented attack on the backbone of Germany’s energy supply as quickly as possible.

The Investigators

The BKA has three main offices. One is in Wiesbaden, where investigators deal with organized crime, narcotics offenses, targeted searches and such things. Another, in Berlin, provides headquarters for its experts on issues including Islamist terrorism. And then there’s the one in Meckenheim near Bonn, in a gray 1970s, box-like building surrounded by orchards and fields, with red-tiled hallways inside. This is the place where one of the most sensational crimes in German criminal history is to be solved, and it looks like some random rural school.

This is where the BKA’s State Protection Department is housed, where the investigators tasked with solving politically motivated crimes work: offenses like attacks, assassinations, espionage and sabotage. In the past, the office investigated the Red Army Faction, domestic left-wing radicals who perpetrated numerous terror attacks in Germany in the 1970s. And the National Socialist Underground, a neo-Nazi cell that killed immigrants, mostly of Turkish descent, across Germany in the early 2000s. More recently, they have been focused on the Reichsbürger movement of militant protesters who deny postwar Germany’s right to exists. Now it has the Nord Stream saboteurs in its crosshairs.

The responsible department is ST 24: State Terrorism. One might assume that dozens of criminologists are working here around the clock researching, searching, and following up on every little lead.

For a time, hundreds of BKA agents were investigating the right-wing extremist madmen around Heinrich XIII Prince Reuss, who had been planning an absurd coup attempt to topple the German government. But only a handful of investigators at most have been assigned to work on the Nord Stream case on a full-time basis.

Sources in Berlin say that a small, dedicated group of skilled investigators should be sufficient. Directing more staff wouldn’t be of much use anyway, they argue, since there are no large groups to observe and they aren’t allowed to conduct investigations in other countries. And if necessary, more BKA people could also be called in addition to support from the Federal Police.

But the perception among investigators is that the will to solve the case is not particularly pronounced in the capital. Politically, it is easier to live with what happened if it remains unclear who is behind the attacks. The process is not being hindered, but neither is there much support from the overarching government ministries. Meanwhile, it is clear to career-oriented ministry officials that there is no glory to be had with this case. If only because the culprits will likely never have to answer for their actions in Germany. Even if they could be identified, it’s very unlikely they would be extradited.

So Berlin is looking away, and that is definitely being registered in agencies where staff is constantly in short supply and procedures have to be prioritized. All of which leads to the investigation falling down the priority list.

Regardless, the BKA unit is led by a chief inspector, an experienced veteran in his mid-50s who is considered a shrewd criminologist by his colleagues.

The German investigators frequently exchange information with officials in Sweden and Poland, and traveled to Warsaw and Stockholm in the spring. However, no agreement has been reached on forming a joint procedure, called a Joined Investigation Team in legal vernacular. Ostensibly because the intelligence agencies involved don’t want to be constantly sharing their information internationally.

Still, sources in all three countries involved say there is tight coordination. Swedish Nord Stream experts are acting more assertively than the Germans, and it is possible charges could be filed before the end of the year. Mats Ljungqvist, the Swedish prosecutor responsible for the investigation there, recently told Radio Sweden that he believes they may be approaching the final phase of the case.

International investigators and agents also say that all the intelligence has been pointing in one direction: towards Kyiv. At least those who are familiar with the evidence and clues.

Alternative Scenarios

In the rest of the world, however, alternative scenarios are still circulating – some spurred by half-baked intelligence, some by amateur military experts and others driven more by domestic political or geostrategic interests.

The American journalist Seymour Hersh, 86, caused quite a stir, for example, when he accused the U.S. of committing the attacks. He claimed that a Norwegian naval vessel had secretly transported American combat divers into the Baltic Sea. The alleged motive: To make sure Russia would no longer be in a position to blackmail Germany with gas supplies. But Hersh didn’t provide any evidence to back up his theory and essential parts of his article later turned out to be false. Hersh justified his reporting by saying that the information had been supplied to him by a source in Washington. The Russian government, though, was delighted and vaunted the baseless story as proof that the U.S. was the real warmonger.

Still others claim that such theories are extremely convenient for the Russians because they distract from the fact that they themselves are the perpetrators. As evidence of this, Russian ship movements in the Baltic Sea, reconstructed by journalists from the public broadcasters of Denmark (DR), Sweden (SVT), Finland (Yle) and Norway (NRK), are frequently cited.

On the night of September 21-22, for example, the Danish Navy encountered a conspicuous number of Russian ships east of Bornholm in exactly the area of the later blasts. The automatic identification systems on the boats had been turned off and they were traveling as unidentifiable “dark ships.”

The 86-meter-long Sibiryakov, a hydrographic research vessel equipped for underwater operations, was also in the area. According to experts, it often accompanies Russian submarines on their secret test dives in the Baltic Sea. Some micro-submarines also have grabber arms that can be used to perform underwater work. Tasks like placing explosive charges.

But why would the Russians blow up their own pipeline? Especially given that they could simply block it at the push of a button? Why deprive yourself of a lever that still might be useful – at least a few years down the road – to resume blackmailing a Germany that is starving for cheap energy?

It’s possible to find reasons, but they are all rather convoluted. One theory holds that Moscow wanted to save itself billions in damages after it violated its own contracts by cutting off promised Nord Stream gas supplies to Germany. If, on the other hand, the pipeline had been blown up by unknown persons, it would be considered a force majeure.

Was It the Russians After All?

The next theory, somewhat more widespread even among Berlin politicians, goes like this: Russia destroyed the pipelines with the aim of later blaming it on the Ukrainians in a way that could undermine Western support for Kyiv. The Andromeda and all other evidence pointing to Ukraine was planted by Russian agents, they say, to throw the Europeans off the scent.

The theory that it was a “false flag” operation performed by the Russians is considered probable by Roderich Kiesewetter, the security and defense policy point man for the center-right Christian Democrats in the Bundestag. Kiesewetter says it would totally fit with Russia’s style to pull off an operation like that perfectly and make it look like the trail leads to Kyiv.

“Of course, we’re following up on those leads as well. But we don’t have any evidence or confirmation of that so far.”

PUBLIC PROSECUTOR LARS OTTE

Conversely, many other intelligence experts consider it highly improbable that Russian agents, who have show a predilection in recent years of more rustic methods – such as brazen and easily exposed political assassinations – could execute such a complex deception maneuver flawlessly.

German Federal Prosecutor Otte emphasized to the Bundestag’s Internal Affairs Committee that they were definitely considering the “working hypothesis” that “state-directed perpetrators from Russia” could be responsible. “Of course, we’re following up on those leads as well,” Otte said. “But we don’t have any evidence or confirmation of that so far.”

Agents tend to believe there is a different, more straightforward explanation for the Russian Navy’s clear presence in the Baltic last late summer: They suspect that Moscow, like the Dutch and the CIA, was not unaware of the plans to attack Nord Stream, and that the ships were there to patrol along the pipeline to protect it from the expected sabotage.

Particularly given that Ukraine apparently had plans to attack another Russian gas pipeline. Sources within the international security scene say that a sabotage squad had plans to attack and destroy the Turkstream pipelines running from Russia through the Black Sea to Turkey. A corresponding tip-off had also reached the German government together with the first warnings of an attack on the Nord Stream pipelines

It is unclear why there was no follow-up on the suspected plot to attack Turkstream.

The Agents

One man who should be in a position to know could be found standing in the ballroom of the British Embassy in Prague on a hot July morning. Sir Richard Moore, the head of Britain’s MI6 intelligence service, had arrived to discuss the global situation with selected intelligence colleagues and diplomats.

Moore is probably one of the best-informed men in the world. If anyone can gain access to all the available data about what happened in the run-up to the explosions under the Baltic Sea, it’s the man with the gray crew cut and narrow reading glasses. DER SPIEGEL was able to ask him a quick question about the Nord Stream attack.

It is one of the few official, and thus mentionable encounters with an intelligence service for this story. Another takes place under similar conditions with CIA head William Burns in the posh American ski resort Aspen in the Rocky Mountains. Each year, the Who’s Who of the U.S. security apparatus gathers there for the Aspen Security Forum. Burns was joined by senior U.S. armed forces officials and national security adviser Jake Sullivan.

When they spoke on the record on the subject of Nord Stream, the top intelligence officials were monosyllabic. Moore said in Prague that he didn’t want to interfere in the investigations of Germany, Denmark and Sweden. And in Aspen, when asked about Nord Stream, only security adviser Sullivan responded, and briefly at that. “As you know, there is an ongoing investigation in multiple countries in Europe,” Sullivan said coolly. “We’ll let that play out, we’ll let them lay out the results of the investigation.”

The British MI6 chief at least provided a bit of context. He said that we have to be prepared for the fact that underwater attacks are now part of the arsenal of modern warfare. His service therefore informs the British government about its own Achilles’ heels, adding that there are quite a few of them. “Seabed warfare,” as such underwater operations are called in military jargon, is not just about pipelines for oil and gas. The power lines of offshore wind farms and especially undersea internet cables are also targets – and potentially even easier to destroy since you don’t need explosives, just the right tools.

Germany’s Response

On September 23, three days before the explosive charges went off, the Andromeda returned to its home port in Rostock. The saboteurs, it is assumed, packed their things, handed in the boat key at the Mola Yachting charter base and walked away via Pier G.

It was one of the most amazing twists in this criminal case, at least at first glance. Why not just sink the boat, including the explosive residue and DNA traces?

Presumably because the investigators would have the been on the trail of the commando much sooner than three months later, because it was precisely such anomalies that they initially searched for: things like rented dive boats. Or charter boats that had suddenly disappeared. But the Andromeda remained just one yacht for hire among hundreds, long since back in port when the seabed shook. And the saboteurs had more than enough time to leave the country and cover their tracks.

Nine months later, on a Saturday afternoon in June, German Interior Minister Nancy Faeser (SPD) was standing at the harbor quay in Rostock’s Warnemünde district. In the background, the masts swayed in the marina; in the foreground the BP84 Neustadt ship towered over everything, 86 meters long, with a 57 millimeter shipboard gun. The Neustadt is the Federal Police force’s newest ship. It’s also in part a response to the Nord Stream attack.

“Increasingly, the lines between internal and external security are becoming blurred, and nowhere is that more conspicuous than here,” the interior minister said. She explained that the attack showed how vulnerable we are. “The Baltic Sea has become a geopolitical hotspot.”

In the background, the Federal Police Orchestra played the maritime anthem “Save the Sea.” It was time for the vessel’s christening. Faeser pulled on a rope and a champagne bottle swung toward the Neustadt. The bottle hit the ship’s hull with a dull clonk, without breaking. A murmur went through the crowd. Sailors believe it is bad luck if the bottle doesn’t break.

CORRECTION: IN AN EARLIER VERSION OF THIS STORY, CIA-CHIEF WILLIAM BURNS WAS CALLED "RICHARD BURNS”. WE CORRECTED THE MISTAKE.